CPA

Contents

- 1 Competitive Position Analyser

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Methods

- 1.3 Models

- 1.4 Reports & Data

- 1.5 The tool

- 1.6 References & Readings

Competitive Position Analyser

Introduction

The Competitive Position Analyser tool is the computerised version of the FACI survey and it is the implementation of the models described in this page. The concept of competitiveness can be traced back to early writing on economics in the 17th and 18th centuries, but has become ever more urgent in the last decades with rapid improvements in transport and communication and a higher level of globalisation. Although competitiveness may be measured by single indicators, such as productivity of labour, a deeper understanding of the competitive standing of firms and countries can be gained by employing multi-dimensional measurements.

The choice of methods depends on a variety of factors, including the perceived need for complexity, data availability and how the results are to be used. The Fisheries and Aquaculture Competitiveness Index (FACI) developed in this deliverable is modelled on the Fisheries Competitive Index (FCI) developed by the Directorate of Fresh Fish Prices in Iceland and the Norwegian College of Fishery Science at the University of Tromsø in 2004-2005. The FACI though expands on the FCI in two directions. First, by developing a national-level FACI that also includes aquaculture. Second, by designing a firm-level FACI that is intended to capture the views of operators of individual firms and is therefore less complex. The national-level FACI consists of 144 items, whereof 44 are taken from the WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 19 are based on data obtained from national, public sources and 81 are based on answers from a survey conducted among specialists in each country. . Whereas the information taken from the GCI analyses the overall competitiveness of the nation, the other sources will throw light on the competitiveness of the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. The firm-level FACI is based on a survey which in the case of firms engaged in the harvesting, processing or marketing of wild capture fish consists of 40 questions, and in the case of aquaculture firms consists of 45 questions.

The FACI was employed to analyse the competitiveness of three fisheries firms in Norway, one in Iceland and one in Newfoundland, and assess the competitive standing of Spain, Iceland, Norway and Vietnam. Newfoundland was also included in the national study, but the comparison is incomplete due to some gaps in the information collected. The firms in Newfoundland and Iceland were found to have a competitive edge over their Norwegian competitors, mostly due to their ability to fend of new entrants, flexible value-chains and high level of R&D development and innovation. At the national level, Iceland, Norway and Spain all ranked close .

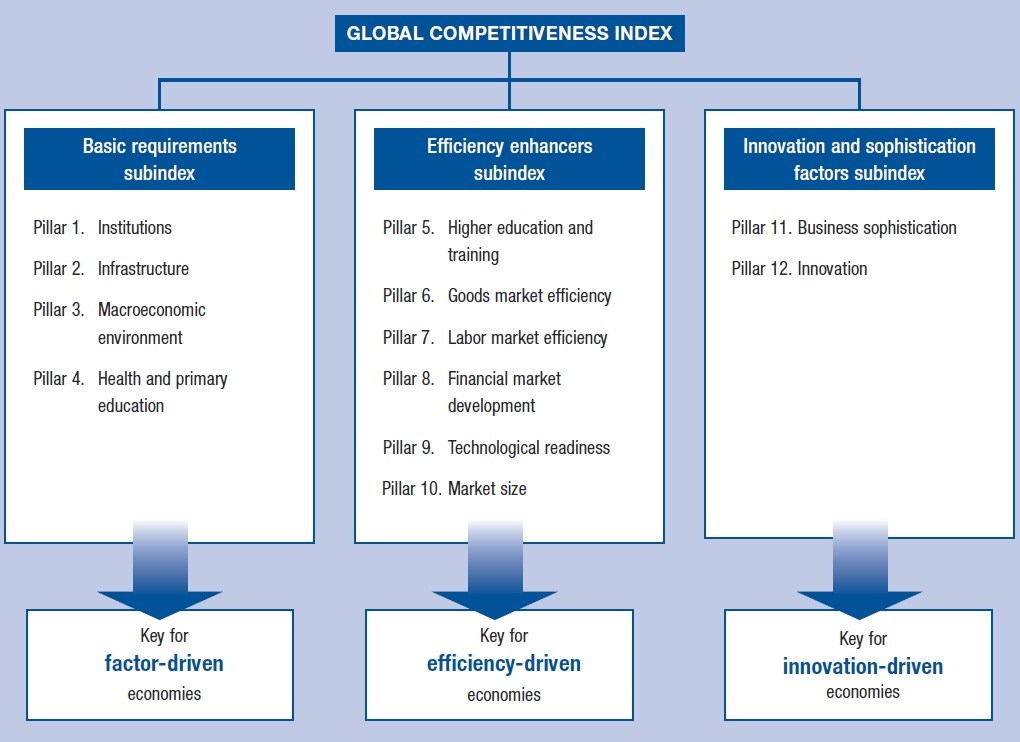

Methods

Currently, the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) is probably the most comprehensive index of its kind. The index defines competitiveness as the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. The most recent analysis covers 138 countries, with a combined output representing 98% of the world GDP. The index, which is compiled annually by the World Economic Forum, combines 114 indicators that capture concepts that matter for productivity and long-term prosperity. As shown in the figure below, these indicators are grouped into 12 pillars: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication, and innovation. These pillars are in turn organised into three sub-indexes: basic requirements, efficiency enhancers, and innovation and sophistication factors. The three sub-indexes are given different weights in the calculation of the overall Index, depending on each economy’s stage of development, as proxied by its GDP per capita and the share of exports represented by raw materials.

Fisheries and Aquaculture Competitiveness Index (FACI)

As outlined above, competitiveness can be measured in a number of ways, using both simple and more complex analytical tools. The choice of methods depends on a variety of factors, including the perceived need for complexity, data availability and how the results are to be used.

he FACI must be flexible enough to meet the needs of the two different end-users; industry and policymakers. With this in mind it was decided to develop two different kinds of competitiveness indexes; a firm-level FACI and a national-level FACI. The firm-level FACI is only intended to capture the views of operators of individual firms and therefore less complex. It is based on a survey which in the case of firms engaged in the harvesting, processing or marketing of wild capture fish consists of 40 questions, and in the case of aquaculture firms consists of 45 questions. The firms are able to access the firm-level FACI, complete the survey and then compare their answers to those provided by other operators. The degree of comparison will, of course, depend on the number of firms using the PrimeDSS, but provided the number of users is large enough, it would be possible to undertake comparison between firms in the same sectors both in the same country as well as between countries, as well as between different sectors. By thus benchmarking themselves against others, firms could gain a better understanding of their competitive standing.

The national-level FACI is modelled on the Fisheries Competitive Index (FCI) developed by the Directorate of Fresh Fish Prices in Iceland and the Norwegian College of Fishery Science at the University of Tromsø in 2004-2005 (Verðlagsstofa skiptaverðs, 2005). The FCI consists of 139 questions and observations which are split between six sub-indexes that make it possible to calculate scores both for the FCI as a whole as well as for individual sub-indexes. This further expands the use of the FCI. The index was applied to the Icelandic and Norwegian fish industries. The national-level FACI consists of 144 items, whereof 44 are taken from the WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 19 are based on data obtained from national, public sources and 81 are based on answers from a survey conducted among specialists in each country. Whereas the information taken from the GCI analyses the overall competitiveness of the nation, the other sources will throw light on the competitiveness of the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. The national-level FACI will therefore yield a comprehensive measure of competitiveness which takes both into account general conditions in the country as well as those that deal specifically with the sectors of interest.

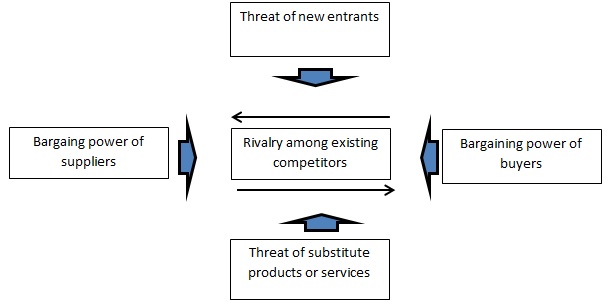

According to Porter (1998, 2008), the nature of competition is embodied in five competitive forces; (1) the threat of new entrants, (2) the threat of substitute products or services, (3) the bargaining power of suppliers, (4) the bargaining power of buyers, and (5) the rivalry among the existing competitors. As shown in the figure below, these forces do interact with each other. Their strength may also vary but together they determine long-term industry profitability.

The threat of entry puts a cap on the profit potential of an industry. When the threat is high, incumbents must keep prices low or increase production capacity to deter new competitors. Within each industry there are usually some entry barriers that deter new firms from entering the market, and give the incumbents some advantages. These may include economies of scale, network effects, customer switching costs, capital requirements, unequal access to distribution channels, restrictive government policy, expected retaliation of incumbents, and some other advantages not related to size, such as favourable geographic locations, and established brand identities.

The power of suppliers varies between industries, but in general a supplier is more powerful if is more concentrated than the industry it sells to, the supplier group does not depend heavily on the industry it is selling to, the firms face switching costs for changing suppliers and the products offered by suppliers are somewhat differentiated.

Buyers can capture more value by forcing down prices, demanding better quality or improved service, and play industry partners against each other. Analogous to suppliers, buyers have more leverage if they are few and large, the industry’s products are similar so that there are ample substitution possibilities, and there are low switching costs.

A high threat of substitutes will reduce profitability by placing a ceiling on prices. A firm can, however, distance itself from others through product performance, marking or other means. High rivalry among existing competitors will reduce the profitability of the firms in an industry. The rivalry can take many forms, including price discounting, new product innovations, advertising campaigns and service and quality improvements. Rivalry will be especially high in cases where there are many competitors and no clear industry leader, industry growth is slow and exit barriers are high. Although some market/firm/industry characteristics may be regarded as only belonging to one specific force category, other characteristics could plausible be classified in two or more different ways. Thus, the value of an output brand could impact on the bargaining power of buyers, threats of substitutes and rivalry among existing competitors. The firm-level FACI builds heavily on the theories of Porter (1998), taking into considerations all five aspects of competition outlined above. As stated earlier, this index is mostly intended for operators of fisheries and aquaculture firms who wish to analyse the competitive standing of their firm. The index consists of 40 questions – 45 in the case of aquaculture – that together yield a solid measure of competitiveness. This deliverable yields the results of a survey that was put to firm operators, but once the PrimeDSS becomes operational it will be possible to access a computerised version of the firm-level FACI, complete the survey online and then obtain a measure of the competitiveness of the firm, both by analysing the data and comparing the competitive standing of the firm to that of other firms. Each questions uses a seven-level Likert scale. Nine of the survey questions refer to the category threat of new entrants. They are as follows

- Institutional barriers (f. ex. licenses, quotas, regulations, location restrictions, water treatment)

- Investment barriers in capital (vessels, equipment, buildings)

- Other form of barriers (marketing, R&D, knowledge)

- Economies-of-scale in production

- Utilisation of economies-of-scale

- Geographical location

- Level of uncertainty in business environment

- Local availability of highly skilled labour

- Availability of qualified experts

The first three items all refer to concrete barrier to entry, such as licenses, quotas, investment, and R&D. The next two refer to the existence and utilisation of economies-of-scale, but companies that produce at a large scale enjoy a cost advantages that new entrants may have difficulties in matching. Geographical location refers to the fact that some firms are well located in terms of cost and ability to meet customer demand. An uncertain business environment may make entry less attractive, and the availability of skilled employees will certainly impact on the threat of entry. The bargaining power of suppliers is analysed on the basis of the following eight questions for fisheries firms (10 for aquaculture firms):

- Bargaining power of suppliers

- Competition among the major suppliers (fisheries)

- Current quality of raw material (fisheries)

- Ability of prices for raw material to reflect changes in (fisheries)

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Ability of prices for seed to reflect changes in (aquaculture)

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Ability of prices for feed to reflect changes in (aquaculture)

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Comparative access to raw material (fisheries)

- Comparative access to seed (aquaculture)

- Comparative access to feed (aquaculture)

- Access to supplier networks

The term “raw material” refers to landings of catch sourced by processors. Catches are by far the most important input for firms engaged in processing and marketing of wild capture fish, while for aquaculture firms the most important inputs are seed and feed. The interest here is in how well prices for these inputs reflect changes in quantity, quality and timing. The term “comparative access” refers to how firms regards their access to inputs (raw material, feed, seed) compared to their competitors. The bargaining power of suppliers is also assessed using a direct question on that issue. The bargaining power of buyers is analysed in terms of eight characteristics:

- Customers´ sensitivity to changes in product price

- Value of brand

- Loyal buyers

- Bargaining power of buyers

- Ability of output prices to reflect changes in

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Diversification of marketing options

Good brand value and loyal buyers will combine to make customers rather insensitive to changes in product prices. The survey also has questions on how firms view the price sensitivity of product prices, i.e. whether the firms regard their product price inelastic or elastic, as well as whether the bargaining power of buyers is weak or strong. Diversification of marketing options refers to whether the firm depends on a single buyer for its product or many buyers. The bargaining power of buyers may also be affected by how well output prices reflect changes in quantity, quality and timing of sale

The bargaining power of buyers is very closely linked to the threat of substitute products or services. Some of the items listed under the bargaining power of buyers, such as customers’ sensitivity to price changes, brand value and consumer loyalty, could just as easily have been listed under substitutes. Here, only two items are classified in this category, namely:

- Production to a niche market

- Availability of substitutes

Customers in niche markets are often willing to pay a premium price for a product that well satisfies their needs. These markets are often characterised by a strong brand and consumer loyalty. The two survey questions here refer to whether the firm is producing to a niche market, and whether substitutes to the product are available in the market. Most of the survey questions in the firm-level FACI are here grouped under the heading “rivalry among existing competitors”. However, many of these items could equally well have been categorised differently. These questions are on the following topics:

- R&D collaboration with technology firms

- Importance of R&D for operation and possibility to increase value added

- Importance of innovation for competitive advantage

- Ability of firm’s part of the value chain to respond to changes in market conditions

- Ability of the whole value chain to respond to changes in market conditions

- Importance of third-party audited labels

- Strength of competitive strategy

- Market share of firm

- Level of cost leadership

- Sophistication of production technology compared to best practice

- Quality of sites for production facilities

- Flexibility to adapt to unpredictable events

- Ability of risk management and insurance to protect against unpredictable negative shocks

- Comparative seed costs (aquaculture)

- Comparative feed costs (aquaculture)

- Comparative production losses due to diseases or other causes (aquaculture)

The first three questions refer to R&D and innovation activities within the firm, to which degree they are done in close collaboration with high-tech firms, and how important they are for increased value added and competitive advantage. Flexibility of the value chain – both as regards the firm itself and the whole value chain – is also important for firms facing competition. Third-party labelling has become very important in the food industry, not least for fisheries and aquaculture. Labelling may open access to markets and also indicate sustainable and environmental friendly production. The market share of firms is important, as is the level of cost leadership. Firms are also asked to indicate how sophisticated their production facilities are compared to their competitors, and assess the quality of the sites used for their production facilities. Two questions refer to the ability of the firms to adjust to unpredictable events, and three questions focus on the costs of feed and seed relative to the firm’s competitors, and comparative production losses due to fish diseases and other causes.

The firm-level FAC yields both an overall score as well as a score for each of the five competitive forces where the former is calculated as the simple average of the other five scores.

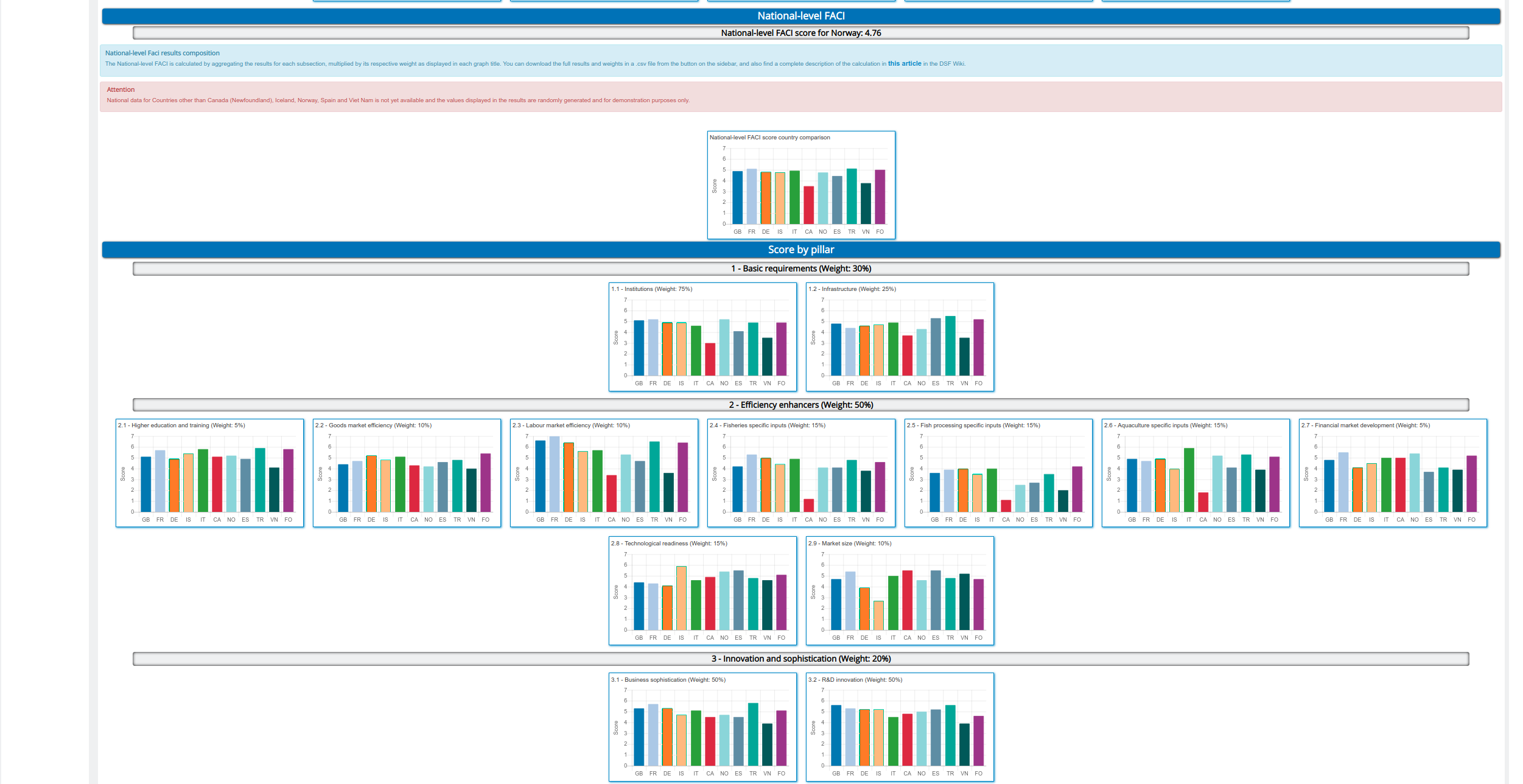

National-level FACI

The national-level FACI is a comprehensive measure that includes both factors influencing each country’s overall competitiveness as well as factors that specifically relate to the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. Most of the indicators related to overall competitiveness are taken from the Global Competitiveness Index, published by the World Economic Forum (2016), but information on the other, more specific indicators was obtained through surveys and from public data collection agencies.

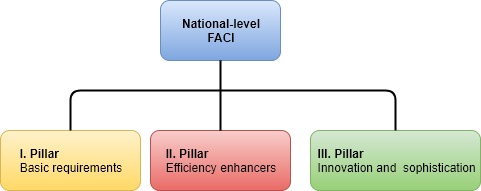

The national-level FACI consists of three pillars; (I) basic requirements, (II) efficiency enhancers, and (III) innovation and sophistication. In contrast to the firm-level FACI, the national-level FACI yields a weighted overall score for each country, as well as a weighted score for each pillar and the sub-indexes contain therein. Basic requirements weigh 30% of the total score, efficiency enhancers 50% and innovation and sophistication 20%.

The first pillar – basic requirements – comprises elements that are essential if firms are to thrive in a competitive, international world. As noted by Acemoglu and Robinson (2012), economic prosperity depends above all on the inclusiveness of economic and political institutions, where inclusiveness is defined as the situation where a large number of people have a say in political decision-making. By contrast, extractive institutions allow a certain elite to rule over and exploit others, thus preventing firms from enjoying competition on a level playing field. As shown in Table 1, there are two subsections within the first pillar, institutions and infrastructure. Institutions are then further subdivided into public institutions and management of fisheries and aquaculture. Public institutions are then finally divided into property rights and public sector performance. There is just one indicator for property rights, namely property rights, but within public sector performance there are three indicators. Well defined and secure property rights are essential for any market-based activity, as are well functioning courts and legal system that make it easy for firms to challenge government actions and/or regulations. Transparent government policy making is also important. The burden of government regulation must however not become too great. For firms operating within the fisheries and aquaculture sectors, it is also important how well these activities are managed by policy makers.

Table 1 Structure of the first pillar, Basic requirements.

| Level | Weight | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st pillar: Basic requirements | 30% | ||

| . A. Institutions | 75% | ||

| .. I. Public institutions | 33% | ||

| ... 1. Property rights | 50% | ||

| .... 1.01 Property rights | 100% | WEF | |

| ... 2. Public sector performance | 50% | ||

| .... 2.01 Burden of government regulation | 33% | WEF | |

| .... 2.02 Efficiency of legal framework in challenging regulations | 33% | WEF | |

| .... 2.03 Transparency of government policy making | 33% | WEF | |

| .. II. Fisheries management | 33% | ||

| ... 3. Stability | 33% | ||

| .... 3.01 Transparency of fisheries management | 33% | Survey | |

| .... 3.02 Objectives of fisheries management | 33% | Survey | |

| .... 3.03 Stability of the allocation of fishing rights | 33% | Survey | |

| ... 4. Research and advice | 33% | ||

| .... 4.01 Actual vs recommended fishing mortality | 20% | Data | |

| .... 4.02 Extent of information gathering by marine research | 20% | Survey | |

| .... 4.03 Information gathering by marine research | 20% | Survey | |

| .... 4.04 Accuracy of forecasts of marine research | 20% | Survey | |

| .... 4.05 Impact of marine research on investments and operation | 20% | Survey | |

| ... 5. Monitoring and inspection | 33% | ||

| .... 5.01 Efficiency of the management system | 50% | Survey | |

| .... 5.02 Illegal/excess catches | 50% | Survey | |

| .. III. Aquaculture management | 33% | ||

| ... 6. Stability | 50% | ||

| .... 6.01 Transparency of aquaculture management | 25% | Survey | |

| .... 6.02 Objectives of aquaculture management | 25% | Survey | |

| .... 6.03 Stability of the allocation of the aquaculture licenses | 25% | Survey | |

| .... 6.04 Efficiency of management - aquaculture | 25% | Survey | |

| ... 7. Research and advice | 50% | ||

| .... 7.01 Extent of information gathering by research for aquaculture | 100% | Survey | |

| . B. Infrastructure | 25% | ||

| .. I. Transport infrastructure | 100% | ||

| .... 8.01 Quality of overall infrastructure | 20% | WEF | |

| .... 8.02 Communication network needs | 20% | Survey | |

| .... 8.03 Communication network restrictions | 20% | Survey | |

| .... 8.04 Cost of domestic transportation | 20% | Survey | |

| .... 8.05 | Cost of cross-border transportation | 20% | Survey |

Table 1 also shows the weighing structure of the FACI. As noted above, the first pillar, Basic requirements, carries a weight of 30%, with institutions thereof weighing 75% and infrastructure weighing 25%. Within institutions, public institutions weigh 33%, fisheries management 33% and aquaculture management 33%. Within public institutions, property rights weigh and public sector performance each weigh 50%. Finally, each of the three indicators of public sector performance weighs 33%. The weight of each section and indicators is shown in the second-last column of Table 1, while the sources are shown in the last column of the table. WEF refers to the 2016-2017 Global Competitiveness Index carried out by the World Economic Forum, data refers to data collected from official sources, and survey refers to the survey carried out among experts in each country.

Table 2 Structure of the second pillar, Efficiency enhancers. Subsections A-C.

| Level | Weight | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd pillar: Efficiency enhancers | 50% | |

| . A. Higher education and training | 5 | |

| .. I. Quality of education | 25% | |

| .... 1.01 Quality of the education system | 33% | WEF |

| .... 1.02 Quality of math and science education | 33% | WEF |

| .... 1.03 Quality of management schools | 33% | WEF |

| .. II. On-the-job training | 75 | |

| .... 2.01 Local availability of specialized training services | 10% | WEF |

| .... 2.02 Extent of staff training | 10% | WEF |

| .... 2.03 Training and education fisheries | 30% | Survey |

| .... 2.04 Training and education fish processing | 30% | Survey |

| .... 2.05 Training and education aquaculture | 30% | Survey |

| . B. Goods market efficiency | 10% | |

| .. I. Competition | 67% | |

| ... 3. Domestic competition | 50% | |

| .... 3.01 Intensity of local competition | 5% | WEF |

| .... 3.02 Extent of market dominance | 5% | WEF |

| .... 3.03 Effect of taxation on incentives to invest | 8% | WEF |

| .... 3.04 Total tax rate | 8% | WEF |

| .... 3.05 Competition for fishing rights (quota) | 15% | Survey |

| .... 3.06 Market for fresh fish - fisheries | 15% | Survey |

| .... 3.07 Market for fresh fish - fish processing | 15% | Survey |

| .... 3.08 Competition between marketing/distributors - marketing | 15% | Survey |

| .... 3.09 Competition between companies that market and distribute seafood products | 15% | Survey |

| ... 4. Foreign competition | 50% | |

| .... 4.01 Prevalence of non-tariff barriers | 15% | WEF |

| .... 4.02 Trade-weighted average tariff rate | 15% | WEF |

| .... 4.03 Current markets - free trade agreements | 45% | Survey |

| .... 4.04 Potential markets - free trade agreements | 25% | Survey |

| .. II. Quality of demand conditions | 33% | |

| .... 5.01 Degree of customer orientation | 10% | WEF |

| .... 5.02 Buyer sophistication | 10% | WEF |

| .... 5.03 Product development - fish processing | 40% | Survey |

| .... 5.04 Product development - aquaculture processing | 40% | Survey |

| . C. Labour market efficiency | 10% | |

| .. I. Flexibillity | 25% | |

| .... 6.01 Flexibility of wage determination | 33% | WEF |

| .... 6.02 Hiring and firing practices | 33% | WEF |

| .... 6.03 Effect of taxation on incentives to work | 33% | WEF |

| .. II. Efficient use of talent | 25% | |

| .... 7.01 Pay and productivity | 10% | WEF |

| .... 7.02 Reliance on professional management | 10% | WEF |

| .... 7.03 Productivity of fishermen | 30% | Data |

| .... 7.04 Wage system fisheries | 30% | Survey |

| .... 7.05 Productivity of employees fish processing | 30% | Data |

| .... 7.06 Wage system fish processing | 30% | Survey |

| .... 7.07 Productivity of labor aquaculture | 30% | Data |

| .... 7.08 Labour skills and productivity - aquaculture | 30% | Survey |

| .. III. Supply of labour | 25% | |

| .... 8.01 Supply of qualified officers | 20% | Survey |

| .... 8.02 Supply of skilled fishermen | 20% | Survey |

| .... 8.03 Supply middle management fish processing | 20% | Survey |

| .... 8.04 Supply of skilled labour fish processing | 20% | Survey |

| .... 8.05 Supply middle management aquaculture | 20% | Survey |

| .... 8.06 Supply of skilled labour aquaculture | 20% | Survey |

| .. IV. Cost of labour | 25% | |

| .... 9.01 Labour cost fisheries | 50% | Data |

| .... 9.02 Labour cost fish processing | 50% | Data |

| . D. Fisheries specific inputs | 15% | |

| .. I. Property rights | 20% | |

| .... 10.01 Permanency of fisheries rights. | 50% | Survey |

| .... 10.02 Transfers of fishing rights between firms | 50% | Survey |

| .. II. Capacity utilization | 20% | |

| .... 11.01 Transfers of fishing rights between vessels | 25% | Survey |

| .... 11.02 Impact of quota system on capacity utilisation | 25% | Survey |

| .... 11.03 Stability of catch for the 5 most important species. | 25% | Data |

| .... 11.04 Impact of authorities on investment decisions | 25% | Survey |

| .. III. Cost items | 30% | |

| .... 12.01 Special taxation fishing | 50% | Data |

| .... 12.02 Oil price | 50% | Data |

| .. IV. Profitability | 30% | |

| .... 13.01 Profit margin | 35% | Data |

| .... 13.02 Capital turnover | 20% | Data |

| .... 13.03 Financial strength | 15% | Data |

| .... 13.04 Ability to use economies of scale | 20% | Survey |

| .... 13.05 Ability to use economies of scope | 10% | Survey |

| . E. Fish processing specific inputs | 15% | |

| .. I. Capacity utilization | 20% | |

| .... 14.01 Distribution of the catch within the year | 50% | Data |

| .... 14.02 Timing of wetfish availability | 50% | Survey |

| .. II. Cost items | 30% | |

| .... 15.01 Cost of electricity | 50% | Data |

| .... 15.02 Supply and cost of fresh water - fish processing | 50% | Survey |

| .. III. Profitability | 30% | |

| .... 16.01 Profit margin | 35% | Data |

| .... 16.02 Capital turnover | 20% | Data |

| .... 16.03 Financial strength | 15% | Data |

| .... 16.04 Ability to use economies of scale | 20% | Survey |

| .... 16.05 Ability to use economies of scope | 10% | Survey |

| . F. Aquaculture specific inputs | 15% | |

| .. I. Property rights | 20% | |

| .... 17.01 Transfers of licenses between firms - aquaculture | 100% | Survey |

| .. II. Capacity utilization | 20% | |

| .... 18.01 Impact of regulations on capacity utilisation - aquaculture | 100% | Survey |

| .. III. Cost items | 30% | |

| .... 19.01 Cost of electricity - aquaculture | 15% | Data |

| .... 19.02 Supply and cost of seedstocks | 30% | Survey |

| .... 19.03 Supply and cost of feed | 55% | Survey |

| .. IV. Profitability | 30% | |

| .... 20.01 Profit margin | 35% | Data |

| .... 20.02 Capital turnover | 20% | Data |

| .... 20.03 Financial strength | 15% | Data |

| .... 20.04 Ability to use economies of scale | 20% | Survey |

| .... 20.05 Ability to use economies of scope | 10% | Survey |

| . G. Financial market development | 5% | |

| .. I. Efficiency | 100% | |

| .... 21.01 Financial services meeting business needs | 33% | WEF |

| .... 21.02 Financing through local equity market | 33% | WEF |

| .... 21.03 Ease of access to loans | 33% | WEF |

| . H. Technological readiness | 15% | |

| .. I. Technological adoption | 10% | |

| .... 22.01 Availability of latest technologies | 50% | WEF |

| .... 22.02 Firm-level technology absorption | 50% | WEF |

| .. II. Fisheries technology | 30% | |

| .... 23.01 Technical level of vessels and mechnical equipment | 33% | Survey |

| .... 23.02 Fishing technology | 33% | Survey |

| .... 23.03 Processing technology on board | 33% | Survey |

| .. III. Fish processing technology | 30% | |

| .... 24.01 General technology - fish processing | 100% | Survey |

| .. IV. Aquaculture technology | 30% | |

| .... 25.01 General technology - aquaculture | 100% | Survey |

| . I. Market size | 10% | |

| .. I. Domestic market size | 50% | |

| .... 26.01 Domestic market size index | 100% | WEF |

| .. II. Foreign market size | 50% | |

| .... 27.01 Foreign market size index | 100% | WEF |

The structure of the second pillar, efficiency enhancers, is similarly shown in Tables 2. This is a much more complex pillar than the first one, with nine subsections and 88 indicators. While some of the subsections here refer to areas mostly within the reach of government, such as higher education and training, other subsections deal with areas over which the firm themselves have more control, such as the access to and utilisation of inputs. Table 2 shows higher education and training, goods market efficiency and labour market efficiency, specific inputs used in fisheries, fish processing and aquaculture, financial market development, technological readiness and market size.

The structure of pillar III – innovation and business sophistication – is far simpler than that of the other two pillars. Here there are only two subsections, business sophistication and R&D innovation. There are 16 indicators within the former subsection and 10 within the latter. Most of these indicators refers to areas over which the firms have good control, but some are also related to areas there the government is more involved.

| Level | Weight | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 3rd pillar: Innovation and sophistication | 20% | |

| . A. Business sophistication | 50% | |

| .... 1.01 Local supplier quantity | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.02 Local supplier quality | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.03 State of cluster development | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.04 Nature of competitive advantage | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.05 Value chain breadth | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.06 Control of international distribution | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.07 Production process sophistication | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.08 Extent of marketing | 3% | WEF |

| .... 1.09 Official marketing support - marketing | 3% | Survey |

| .... 1.10 Marketing operations - wild fisheries | 11% | Survey |

| .... 1.11 Marketing operations - aquaculture products | 11% | Survey |

| .... 1.12 Competition among major suppliers - fisheries | 11% | Survey |

| .... 1.13 Cooperation in the value chain - fisheries | 11% | Survey |

| .... 1.14 Cooperation in the value chain - fish processing | 11% | Survey |

| .... 1.15 Competition among major suppliers - fish processing | 11% | Survey |

| .... 1.16 Cooperation along the value chain - aquaculture | 11% | Survey |

| . B. R&D Innovation | 50% | |

| .... 2.01 Capacity for innovation | 8% | WEF |

| .... 2.02 Quality of scientific research institutions | 8% | WEF |

| .... 2.03 Company spending on R&D | 5% | WEF |

| .... 2.04 University-industry collaboration in R&D | 8% | WEF |

| .... 2.05 Availability of scientists and engineers | 8% | WEF |

| .... 2.06 PCT patent applications | 5% | WEF |

| .... 2.07 R&D Fishing technology fisheries | 15% | Survey |

| .... 2.08 R&D Processing technology fisheries | 15% | Survey |

| .... 2.09 R&D Processing technology fish processing | 15% | Survey |

| .... 2.10 R&D - aquaculture equipment | 15% | Survey |

Models

The concept of competitiveness can be traced back to early writing on economics in the 17th and 18th centuries, but has become ever more urgent in the last decades with rapid improvements in transport and communication and a higher level of globalisation. Although competitiveness may be measured by single indicators, such as productivity of labour, a deeper understanding of the competitive standing of firms and countries can be gained by employing multi-dimensional measurements. Currently, the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), developed and compiled by the World Economic Forum, is probably the most comprehensive index of its kind. The choice of methods depends on a variety of factors, including the perceived need for complexity, data availability and how the results are to be used.

The Fisheries and Aquaculture Competitiveness Index (FACI) developed in this deliverable is modelled on the Fisheries Competitive Index (FCI) developed by the Directorate of Fresh Fish Prices in Iceland and the Norwegian College of Fishery Science at the University of Tromsø in 2004-2005. The FACI though expands on the FCI in two directions. First, by developing a national-level FACI that also includes aquaculture. Second, by designing a firm-level FACI that is intended to capture the views of operators of individual firms and is therefore less complex. The national-level FACI consists of 144 items, whereof 44 are taken from the WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 19 are based on data obtained from national, public sources and 81 are based on answers from a survey conducted among specialists in each country. Whereas the information taken from the GCI analyses the overall competitiveness of the nation, the other sources will throw light on the competitiveness of the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. The firm-level FACI is based on a survey which in the case of firms engaged in the harvesting, processing or marketing of wild capture fish consists of 40 questions, and in the case of aquaculture firms consists of 45 questions. In PrimeFish, a computerised decision support system (CPA) was developed that can be used by the industry and/or policymakers. The CPA is based on the FACI and a suit of simulation/forecasting models to be compiled in WP5 and developed as an operational web-based software tool. A computerised version of the FACI will therefore form a part of the PrimeDSS software.

The FACI was employed to analyse the competitiveness of three fisheries firms in Norway, one in Iceland and one in Newfoundland, and assess the competitive standing of Spain, Iceland, Norway and Vietnam. Newfoundland was also included in the national study, but the comparison is incomplete due to some gaps in the information collected. The firms in Newfoundland and Iceland were found to have a competitive edge over their Norwegian competitors, mostly due to their ability to fend of new entrants, flexible value-chains and high level of R&D development and innovation. At the national level, Iceland, Norway and Spain all ranked close to one another, with Vietnam at a competitive disadvantage. While some of the issues standing in the way of improved competitiveness can be traced to the general social issue facing firms, e.g. poor institutions and infrastructure, and can only be addressed through government, others lie within the realm of the firms, e.g. poor financial performance and inability to take advantage of economies-of-scale.

Reports & Data

Firm-level FACI - Fisheries

As mentioned above, the firm-level FACI can both be applied to firms engaged in fisheries and aquaculture. This section only deals with the former, and compares results from one firm Iceland, one from Newfoundland and three Norwegian firms engaged in harvesting and processing of wild capture fish. Each firm’s scoring of individual indicators is presented in the table below:

Questions and responses – firm level FACI – Threat of new entrants

| Theme | Question | Ice.1 | New1 | Nor1 | Nor2 | Nor3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institutional barriers | There are significant institutional barriers (f. ex. licenses, quotas, regulations) to entry in my industry (1=not at all; 7=make entry impossible) | 7 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| Real capital barriers | Entry into my industry requires investment in capital (vessels, equipment, buildings) that (1=does not deter entry at all; 7=deters entry completely) | 5 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Other investment barriers | Entry into my industry requires other forms of investment (marketing, R&D, knowledge) that (1=does not deter entry at all; 7=deters entry completely) | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Scale economics | Does this type of production enjoy economies of scale (1=not at all; 7=to a huge degree) | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 2 |

| Firm scale economics | The firm takes advantage of its economies of scale (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Location | The firm is well geographically located in terms of costs and ability to meet customer demand (1=not at all; 7=very well located) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| Uncertainty | How large uncertainty is there in your business environment? (1=none at all; 7=very great) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Labour availability | High skilled labour in your company’s locations is (1=not readily available; 7=readily available) | 6 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Expert availability | Qualified experts are (1=not readily available; 7=readily available) | 6 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

Questions and responses – firm level FACI – Bargaining power of suppliers

| Theme | Question | Ice.1 | New1 | Nor1 | Nor2 | Nor3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier power | The bargaining power of suppliers is (1=weak; 7=strong)| | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| Supplier competition | Competition among the firm‘s major suppliers is (1=nonexistent; 7=fierce) | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| Quality raw material | Quality of raw material is currently (1=poor; 7=excellent) | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Quality and price | How well do prices for raw materials reflect changes in Quality (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 5 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 3 |

| Quantity and price | How well do prices for raw materials reflect changes in Quantity (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 2 |

| Timing and price | How well do prices for raw materials reflect changes in Timing (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Access raw materials | Compared to your most important competitors, your access to raw material is currently (1=very difficult; 7=very easy) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Supplier networks | The firm has access to supplier networks (1=not at all; 7= very good access) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

Questions and responses – firm level FACI – Bargaining power of buyers

| Theme | Question | Ice.1 | New1 | Nor1 | Nor2 | Nor3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product price sensitivity | My customers are sensitive to changes in product price (1=not at all; very much so) | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Brand value | The brand of my product is valuable ?(1=not valuable at all; 7=immensely valuable) | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Loyalty buyers | The buyers of my product are loyal (1=not at all; 7=very much so) | 7 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Buyer power | The bargaining power of buyers is (1=weak; 7=strong) | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Quality and price | How well do prices for your output reflect changes in Quality (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 5 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| Quantity and price | How well do prices for your output reflect changes in Quantity (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| Timing and price | How well do prices for your output reflect changes in Timing (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Diversification | How diversified are the marketing options (does the firm depend on one buyer or many) (1=not at all; 7=very diversified) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

Questions and responses – firm level FACI – Threat of substitute products or services

| Theme | Question | Ice.1 | New1 | Nor1 | Nor2 | Nor3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

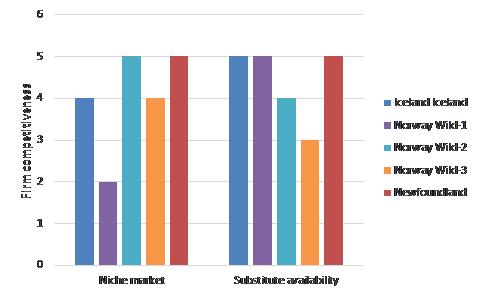

| Niche market | The firm is producing to a niche market (1=not all; 7=completely) | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Substitute availability | There are substitutes to my products available in the market (1=not at all; 7=many substitutes exist) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

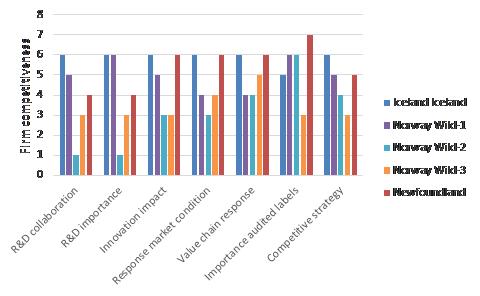

Questions and responses – firm level FACI – Rivalry of existing competitors

| Theme | Question | Ice.1 | New1 | Nor1 | Nor2 | Nor3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R&D collaboration | Research and development within the firm is done in close collaboration with technology firms (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 6 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| R&D importance | How important is R&D for your operation and possibility to increase value added? (1=not important; 7=very important) | 6 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 3 |

| Innovation impact | Innovation makes it possible for my firm to retain a competitive advantage (1=not at all; 7=highly) | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Response market condition | How capable is your part of the value chain of responding to changes in market conditions? (1=not capable; 7=very capable) | 6 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Value chain response | How capable is your whole value chain of responding to changes in market conditions? (1=not capable; 7=very capable) | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Importance audited labels | How important are third-party audited labels to your operation (1=not important; 7=very important) | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| Competitive strategy | The competitive strategy of my firm is (1=weak; 7=powerful) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

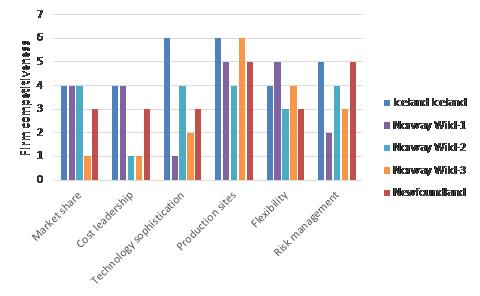

| Market share | The market share of the firm is (1=less than 1%; 7=larger than 10%) | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Cost leadership | The firm is a cost leader (1=not at all; 7=very much so) | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Technology sophistication | How sophisticated is your production technology compared to best practice (1=not at all; 7=very sophisticated) | 6 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Production sites | The firm has access to good sites for its production facilities (1=agree completely; 7=disagree completely) | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| Flexibility | How much flexibility does your firm have in adapting to unpredictable events? (1=none at all; 7=complete flexibility) | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Risk management | To what extent does risk management and insurance protect against unpredictable negative shocks? (1=not at all; 7=completely) | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

Total competitiveness

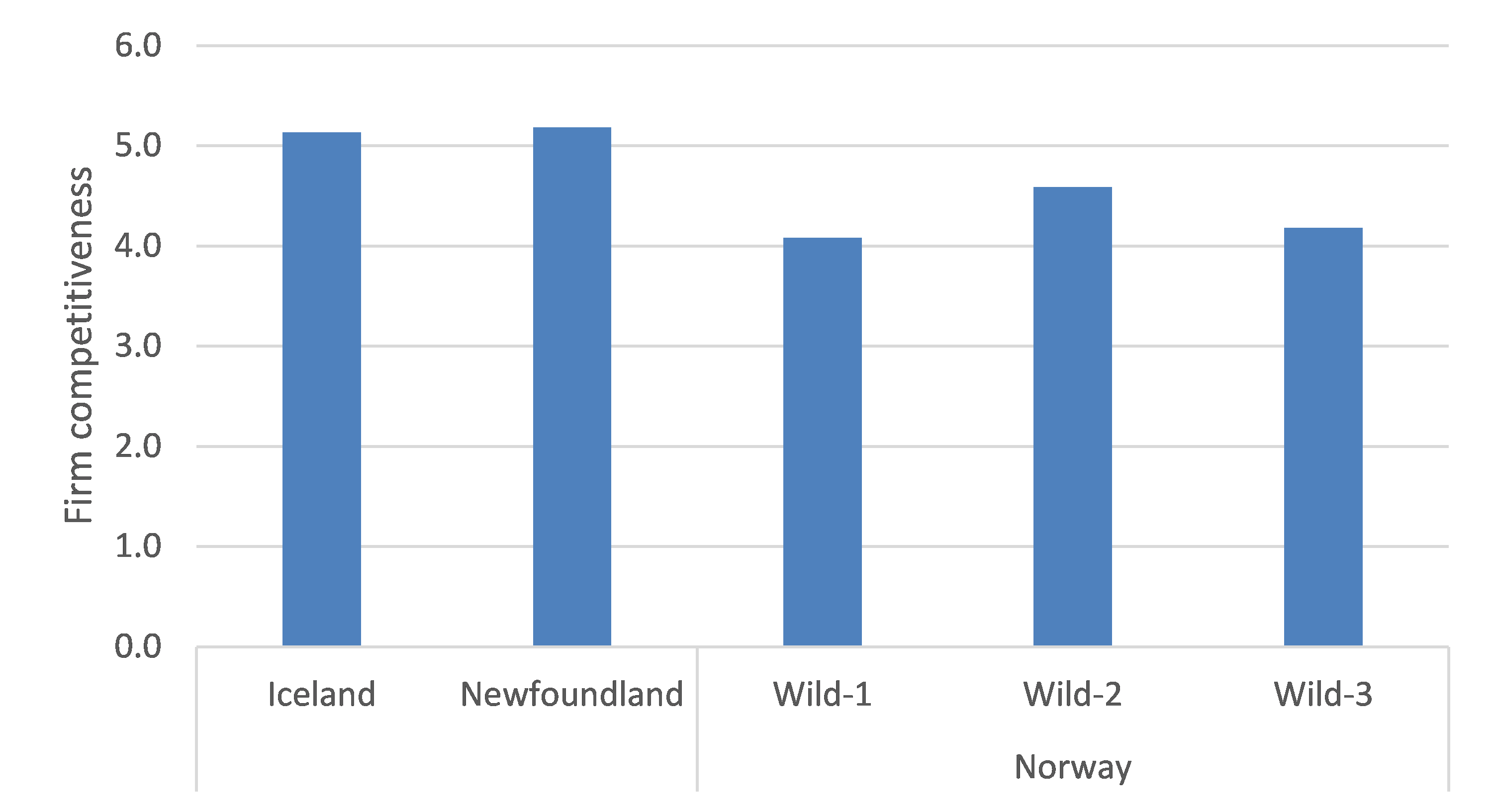

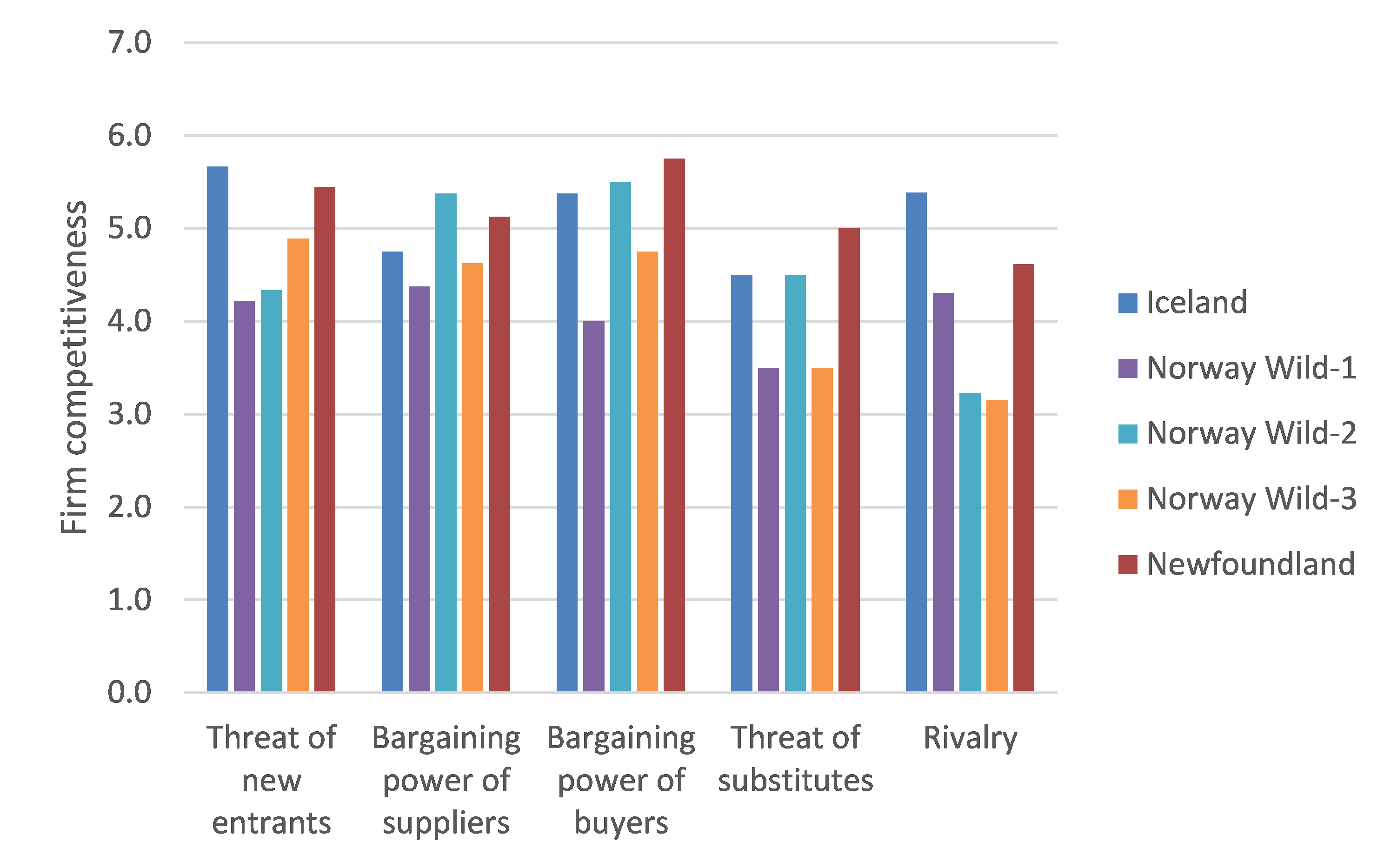

The scores for aggregated competitiveness for each of the sampled firms are presented in Figure 4. The Newfoundland and Icelandic firms receives scores of 5.2 and 5.1, while the Norwegian firms received considerably lower scores, or in the range 4.1-4.6.

Competitive forces

By going one step beyond the total competitiveness score and looking at how the firms rank in terms of each competitive force, it is possible to gain a better insight into the firms’ competitive position. As shown in Figure 5, the Icelandic firm and the Newfoundland firm each score highest in two categories, with the difference between these two firms and the three Norwegian firms especially pronounced as regards the threat of new entrants and rivalry among competitors. The figure also reveals considerable differences between individual Norwegian firms.

Individual indicators

Looking at the individual indicators for each competitive force can further illustrate differences and similarities among firms. In what follows the results are briefly discussed.

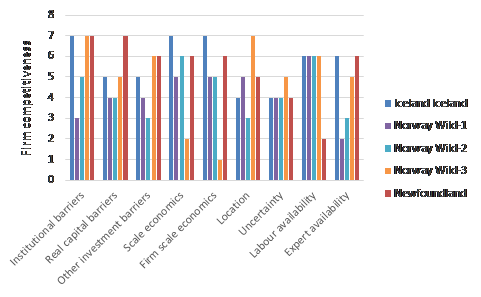

Threat of new entrants

Threat of new entrants is measured by nine individual indicators. Here the Icelandic and Newfoundland firms received the highest score. The survey reveals the existence of substantial barriers to entry, with the Icelandic firms in addition enjoying greater economies of scale and be able to take advantage of that position. The Newfoundland and Norwegian firms have a more advantageous location, but Newfoundland does not have as good access to qualified labour as the other four firms. Qualified experts are more readily available in Newfoundland and Iceland than in Norway.

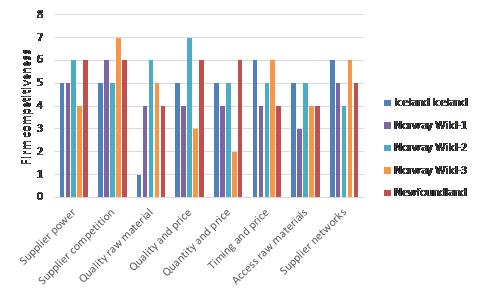

Bargaining power of suppliers

Bargaining power of suppliers is measured through eight individual indicators. Here, one of the Norwegian firms performs much better than the firms in the survey (Figure 7). At the time of the survey, the quality of the raw material available to the Icelandic firm appears to have been very poor. Contrary to what could have been expected for a firm operating under an ITQ management system in fisheries, the relationship between price on the one hand and quality, quantity and timing is not as strong for the Icelandic firm as some of the Norwegian firms and the Newfoundland firm.

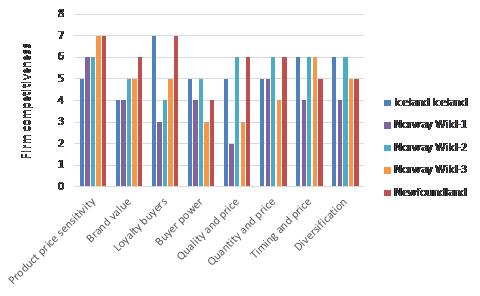

Bargaining power of buyers

The category bargaining power of buyers is measured through eight individual indicators. All the firms believe their buyers are quite sensitive to price changes, but do not regard their brand as particularly valuable (Figure 8). The customers of the Icelandic and Newfoundland firms are far more loyal but all firms rank the power of buyers as relatively similar. The firms have very different views on the relationship between output price and quality.

Threat of substitute products or services

The threat from substitutes is measured by two indicators. Both indicate the firms do have access to niche markets and that substitutes are available (Figure 9).

Rivalry among existing competitors

Rivalry among the existing firms is measured by 13 individual indicators (figure 10). Here the Icelandic firm performs better according to 10 of the indicators. According to the Icelandic firm, R&D collaboration is to a much higher degree conducted in close collaboration with technology firms, and R&D and innovation is regarded vital to maintain a competitive edge. The firm has also more sophisticated technology than its competitors. The Icelandic and Newfoundland value chains are also more flexible and better able to adjust to market condition.

National-level FACI

In the following sections the results from the competitiveness estimation are presented, first the aggregate scores, then the scores for each of the three main pillars (aggregation level 1) and then the score for the subsections within each pillar (aggregation level 2). All scoring is done using a seven step Likert scale. In some instances, data have not been available for certain countries. In particular, this applies to some of the hard data and most frequently for Newfoundland and Vietnam. When one indicator is missing, we have disregarded this from the calculation of the lowest aggregation level for the country in question. For Newfoundland, some themes had several indicators with missing data. Here we have not calculated aggregate level scoring, hence some tables have missing numbers for Newfoundland.

Aggregation level 1 and 2

The national-level FACI was applied to five countries; Norway, Iceland, Spain, Newfoundland and Vietnam. As Newfoundland-Labrador is not an independent country but one of the provinces that make up Canada, the WEF scores for Canada are used for Newfoundland. The hard data and survey is though only based on information from sources in Newfoundland. The data for Newfoundland has some gaps, but the data for the other four countries is almost complete. Because of this, no overall score is calculated for Newfoundland, but where possible scores are presented for individual pillars and subsections, as well as each indicator. Norway, Iceland and Spain all have a similar overall score of 4.8-4.9, while Vietnam gets a score of 3.9 (Table 5). The difference between the European countries and Vietnam is especially large in relation to pillar I, basic requirements, both as regards institutions and infrastructure. Norway and Iceland have a similar score for this first pillar, 4.9 and 5.0, with Spain receiving a score of 4.5. This is mostly due to the Nordic scores getting higher scores for their institutions, but Spain has better infrastructure. The European countries all receive similar scores for pillar II, Efficiency enhancers, and pillar III, Innovation and sophistication, with Vietnam lagging behind in both categories. Newfoundland ranks in between for innovation and sophistication, but due to the lack of data no overall score is calculated for Newfoundland for pillars I and II.

Table 5 Total and first two category levels of competitiveness

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 3.9 | |

| 1 Basic requirements | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 3.5 | |

| 1.1 Institutions | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 3.5 | |

| 1.2 Infrastructure | 4.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| 2 Efficiency enhancers | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4,2 | |

| 2.1 Higher education and training | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.8 |

| 2.2 Goods market efficiency | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 3.9 |

| 2.3 Labour market efficiency | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 3,1 | 3,3 |

| 2.4 Fisheries specific inputs | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.9 | |

| 2.5 Fish processing specific inputs | 4.1 | 5,8 | 5,0 | 2,3 | 3,6 |

| 2.6 Aquaculture specific inputs | 5.3 | 4,0 | 4.3 | 4,1 | |

| 2.7 Financial market development | 5.4 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 3.8 |

| 2.8 Technological readiness | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 4.7 |

| 2.9 Market size | 4.6 | 2.7 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.2 |

| 3 Innovation and sophistication | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.8 |

| 3.1 Business sophistication | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 3.8 |

| 3.2 R&D Innovation | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 3.7 |

Pillar I Basic requirements

This section goes into detail on the two components of the first pillar – institutions and infrastructure. We first discuss the he institutions subsection consisting of sections on public institutions, fisheries management and aquaculture management. Subsequent sections discuss these areas again in more detail.Public institutions are much higher ranked in Norway and Iceland and Newfoundland than in Spain and Vietnam (Table 6). This is both due to stronger property rights in these countries and better public sector performance. Fisheries management scores highest in Iceland and Norway, but aquaculture management is considered better in Norway and Spain. Spain has the best infrastructure, followed by Iceland, Norway and Newfoundland and Vietnam having the lowest scores.

Table 6 Basic requirements and two following aggregation levels of competitiveness

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Basic requirements | 4.9 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 3.5 | |

| 1.1 Institutions | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 3.5 | |

| 1.1.1 Public institutions | 5.7 | 5.4 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 3.8 |

| ........Property rights | 6.2 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 4.0 |

| ........Public sector performance | 5.2 | 5.0 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 3.5 |

| 1.1.2 Fisheries management | 5.1 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 2.8 |

| ........Stability | 5.4 | 6.1 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 2.9 |

| ........Research and advice | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 2.7 |

| ........Monitoring and inspection | 4.6 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 2.9 |

| 1.1.3 Aquaculture management | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 3.8 | |

| ........Stability | 4.8 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.2 | |

| ........Research and advice | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 3.4 | |

| 1.2 Infrastructure | 4.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| 1.2.1 Transport infrastructure | 4.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

Fisheries management

There is relatively large variation between the countries in the stability of fisheries management. It is considered very high in Iceland with Norway following with a score about 0,7 lower.Spain is almost a full point behind again and Newfoundland and Vietnam registering a significant lower stability (Table 7). Research and advice sees less variation between the European countries, with score slightly higher in Norway than in Iceland and Spain. Newfoundland and Vietnam again scores worst. Monitoring and inspection is best in Iceland, with Norway and Newfoundland receiving the same score. Spain and Vietnam have the lowest monitoring and inspection scores.

Table 7 Fisheries management and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1.2 Fisheries management | 5.1 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 2.8 | |

| ....Stability | 5.4 | 6.1 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 2.9 | |

| Transparency of fisheries management | 5.3 | 6.7 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 3.4 | Surv |

| Objectives of fisheries management | 5.2 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.3 | Surv |

| Stability of allocation of fishing rights | 5.7 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 2.0 | Surv |

| ....Research and advice | 5.2 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 2.7 | |

| Actual vs recommended fishing mortality | 6.2 | 2.2 | na | na | na | Data |

| Extent of information gathered by research | 5.3 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 3.7 | Surv |

| Information gathering by marine research | 5.3 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 5.2 | 3.7 | Surv |

| Accuracy of forecasts by marine research | 4.9 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 2.8 | Surv |

| Impact of research on investments and operations | 4.3 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 3.4 | Surv |

| ....Monitoring and inspection | 4.6 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 2.9 | |

| Efficiency of management system | 5.9 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 2.6 | Surv |

| Illegal/excess catches | 3.4 | 5.2 | 2.0 | 5.5 | 3.1 | Surv |

Aquaculture management

Aquaculture is a major industry in Norway, Spain and Vietnam with Iceland being a relative newcomer. No data on aquaculture was available from Newfoundland. Stability is highest in Norway, with relatively small differences between the others. Norway’s leading position is due to generally higher scores on all the indicators. Apart from Vietnam, scoring the worst, there are relatively small differences between countries on in research and advice, but Spain in a slight lead (Table 8).

Table 8 Aquaculture management and individual indicators

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1.3 Aquaculture management | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 3.8 | ||

| ....Stability | 4.8 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.2 | ||

| Transparency of aquaculture management | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.2 | Surv | |

| Objectives of aquaculture management | 4.4 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4.2 | Surv | |

| Stability of allocation of aquaculture licenses | 5.5 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 4.8 | Surv | |

| Efficiency of management - aquaculture | 4.5 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 3.5 | Surv | |

| ....Research and advice | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 3.4 | ||

| Extent of information gathered by research | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 3.4 | Surv |

Infrastructure

Infrastructure in Spain appears to be far better than in any of the other four countries, not least because of relatively low transport costs (Table 9). Iceland and Spain receive similarly high scores for their communication systems. Norway in general scores wore than Spain for all indicators, but sees less costly transportation than Iceland. Both Newfoundland and Vietnam have poorer scores, with transportation costs and communication network needs scoring particularly badly for the former.

Table 9 Fisheries management and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2 Infrastructure | 4.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 | |

| ....Transport infrastructure | 4.2 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 3.5 | |

| Quality of overall infrastructure | 4.8 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 3.6 | WEF |

| Communication network needs | 3.8 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 3.5 | Surv |

| Communication network restrictions | 3.9 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 3.1 | Surv |

| Cost of domestic transportation | 4.0 | 3.2 | 5.3 | 2.3 | 3.5 | Surv |

| Cost of cross-border transportation | 4.4 | 3.6 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 3.8 | Surv |

Pillar II Efficiency enhancers

This pillar consists of a number of quite diverse subsections that measure the competitiveness of the country in terms of quality and efficiency of education, markets, inputs and technology. Norway, Iceland and Spain all receive a score of 4,8-4,9 for the pillar as a whole, but there are some important discrepancies (Table 10). Iceland receives the highest score for education and training, goods market efficiency, for inputs into harvesting and processing of wild capture fish, and technological readiness, but has an inefficient financial system and small markets. Norway has the best aquaculture sector while Spain, Newfoundland and Vietnam enjoy the largest markets.

Table 10 Efficiency enhancers and two following aggregation levels of competitiveness

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Efficiency enhancers | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4,2 | |

| 2.1 Higher education and training | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.8 |

| 2.1.1 Quality of education | 5.3 | 5.7 | 4.4 | 5.4 | 3.7 |

| 2.1.2 On the job training | 5.0 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 3.8 |

| 2.2 Goods market efficiency | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 3.9 |

| 2.2.1 Competition | 4.1 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| ......Domestic competition | 4.2 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| ......Foreign competition | 4.1 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.9 |

| 2.2.2 Quality of demand conditions | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 3.2 |

| 2.3 Labour market efficiency | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 3,3 | |

| 2.3.1 Flexibility | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 4.9 | 4.2 |

| 2.3.2 Efficient use of talent | 5,1 | 5,5 | 3.9 | 3,3 | 4,7 |

| 2.3.3 Supply of labour | 5.1 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 4.1 |

| 2.3.4 Cost of labour | 4.8 | 3.1 | 4.5 | ||

| 2.4 Fisheries specific inputs | 5.1 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 4.9 | |

| 2.4.1 Property rights | 5.4 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 6.1 |

| 2.4.2 Capacity utilization | 3.9 | 5.9 | 5,0 | 2.8 | 3,2 |

| 2.4.3 Cost items | 7.0 | 3.6 | 7.0 | 7.0 | |

| 2.4.4 Profitability | 3.8 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 2,2 | 3.1 |

| 2.5 Fish processing specific inputs | 4.1 | 5,8 | 5,0 | 3,6 | |

| 2.5.1 Capacity utilization | 2.9 | 4.0 | 5,5 | 2,5 | 3,8 |

| 2.5.2 Cost items | 5,3 | 6,8 | 5,7 | 4,3 | 3,7 |

| 2.5.3 Profitability | 3.7 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 3.3 | |

| 2.6 Aquaculture specific inputs | 5.3 | 4,0 | 4.3 | 4,1 | |

| 2.6.1 Property rights | 6.0 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 1.3 | |

| 2.6.2 Capacity utilization | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 4.8 | |

| 2.6.3 Cost items | 4,6 | 5,1 | 4,6 | 5,1 | |

| 2.6.4 Profitability | 5.5 | 1.8 | 2.8 | 4.6 | |

| 2.7 Financial market development | 5.4 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 3.8 |

| 2.7.1 Efficiency | 5.4 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 3.8 |

| 2.8 Technological readiness | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 4.7 |

| 2.8.1 Technological adoption | 6.3 | 6.2 | 5.1 | 5.7 | 4.3 |

| 2.8.2 Fisheries technology | 5.4 | 6.3 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 3.3 |

| 2.8.3 Fish processing technology | 4.1 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 5.0 |

| 2.8.4 Aquaculture technology | 6.3 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.8 |

| 2.9 Market size | 4.6 | 2.7 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.2 |

| 2.9.1 Domestic market size | 4.2 | 1.9 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 4.5 |

| 2.9.2 Foreign market size | 5.0 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

Higher education and training

The category higher education and training consists of education and on-the-job training. Only the latter has indicators specific for the survey and is hence detailed in Table 11 below. Iceland scores slightly higher than Norway in this subsection, mainly because training and education in fish processing seems to be better in Iceland. Spain and Newfoundland have the same overall score. Vietnam appears to lag behind the other countries on all accounts.

Table 11 On-the-job training and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 Higher education and training | 5.1 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.8 | |

| ....On the job training | 5.0 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 3.8 | |

| Local availability of specialized training services | 5.8 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 5.8 | 3.7 | WEF |

| Extent of staff training | 5.5 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 3.9 | WEF |

| Training and education fisheries | 4.6 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 3.8 | Surv |

| Training and education fish processing | 3.7 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.3 | Surv |

| Training and education aquaculture | 5.1 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 4.4 | Surv |

Goods market efficiency

Efficiency in the goods market appears to be quite similar in all five countries, although Iceland and Spain score higher than the other three countries (Table 12). Iceland enjoys a competitive advantage both as regards domestic and foreign competition. Taxes have a detrimental effect on competitiveness in Spain, while Vietnam suffers from lack of access to international markets due to tariffs and on-tariff barriers. The quality of demand conditions is best in Spain, but quite similar in Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland.

Table 12 Goods market efficiency and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.2.1 Competition | 4.1 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.2 | |

| ....Domestic competition | 4.2 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.5 | |

| Intensity of local competition | 5.1 | 4.8 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 5.0 | WEF |

| Extent of market dominance | 4.7 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 3.6 | WEF |

| Effect of taxation on incentives to invest | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.6 | WEF |

| Total tax rate | 3.5 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 3.5 | WEF |

| Competition for fishing rights (quota) | 3.8 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | Survey |

| Market for fresh fish - fisheries | 5.1 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 3.0 | 5.4 | Survey |

| Market for fresh fish - fish processing | 2.4 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 5.2 | Survey |

| Competition between marketing/distributors - marketing | 5.2 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 5.4 | Survey |

| Competition between companies that market and distribute seafood products | 5.2 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 5.4 | Survey |

| ....Foreign competition | 4.1 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.9 | |

| Prevalence of non-tariff barriers | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 3.9 | WEF |

| Trade-weighted average tariff rate | 5.2 | 5.3 | 4.0 | 5.3 | 2.3 | WEF |

| Current markets - free trade agreements | 4.3 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.6 | Surv |

| Potential markets - free trade agreements | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.8 | Surv |

| 2.2.2 Quality of demand conditions | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 3.2 | |

| Degree of customer orientation | 5.6 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 4.1 | WEF |

| Buyer sophistication | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 3.5 | WEF |

| Product development - fish processing | 3.3 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | Surv |

| Product development - aquaculture processing | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 3.0 | Surv |

Labour market efficiency

Labour market efficiency is highest in Iceland and Norway, not least because of far higher productivity in harvesting and fish processing (Table 13). Supply of labour scores similarly in Iceland, Norway and Spain, but Newfoundland and Vietnam appear to be affected by the availability of good labour.

Table 13 Labour market efficiency and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.3.2 Efficient use of talent | 5,1 | 5,5 | 3.9 | 3,3 | 4,2 | |

| Pay and productivity | 4.9 | 4.9 | 3.6 | 4.9 | 4.0 | WEF |

| Reliance on professional management | 6.2 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 3.6 | WEF |

| Productivity of fishermen | 5.8 | 6.5 | 3.6 | na | na | Data |

| Wage system fisheries | 5.4 | 5.9 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 2.8 | Survey |

| Productivity of employees fish processing | 3.9 | 5.8 | 2.7 | na | na | Data |

| Wage system fish processing | 4.1 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 6.0 | Survey |

| Productivity of labor aquaculture | na | na | na | na | na | Data |

| Labour skills and productivity - aquaculture | 5.8 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.0 | Survey |

| 2.3.3 Supply of labour | 5.1 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 4.2 | 4.1 | |

| Supply of qualified officers | 5.0 | 6.0 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.2 | Survey |

| Supply of skilled fishermen | 5.5 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.2 | Survey |

| Supply middle management fish processing | 5.0 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 4.0 | 3.8 | Survey |

| Supply of skilled labour fish processing | 4.1 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 3.0 | 4.0 | Survey |

| Supply middle management aquaculture | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 4.8 | Survey |

| Supply of skilled labour aquaculture | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 4.8 | Survey |

| 2.3.4 Cost of labour | 4.8 | 3.1 | 4.5 | na | na | |

| Labour cost fisheries | 4.8 | 3.1 | 4.5 | na | na | Data |

| Labour cost fish processing | na | na | na | na | na | Data |

Fisheries specific inputs

The fisheries specific inputs score countries in terms of quality of the property rights in management, capacity utilisation, taxation and oil costs, and profitability. Iceland scores highly here, mainly because of the good quality of the property rights system employed in the harvesting sectors, high degree of capacity utilisation and profitability. However, taxation in the Icelandic fisheries erodes some of the competitive advantage. Newfoundland performs poorly in this subsection.

Table 14 Fisheries specific inputs and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4.1 Property rights | 5.4 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 6.1 | |

| Permanency of fisheries rights. | 5.8 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 6.2 | Survey |

| Transfers of fishing rights between firms | 5.0 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 3.8 | 6.0 | Survey |

| 2.4.2 Capacity utilization | 3.9 | 5.9 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 3,2 | |

| Transfers of fishing rights between vessels | 4.0 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 3.0 | 5.5 | Survey |

| Impact of quota system on capacity utilisation | 4.5 | 6.3 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.7 | Survey |

| Stability of catch for the 5 most important species. | 3.2 | 4.6 | na | na | 3.2 | Data |

| Impact of authorities on investment decisions | 4.1 | 6.1 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 2.4 | Survey |

| 2.4.2 Cost items | 7.0 | 3.6 | 7.0 | na | 7.0 | |

| Special taxation fishing | 7.0 | 3.6 | 7.0 | na | 7.0 | Data |

| Oil price | na | na | na | na | na | Data |

| 2.4.3 Profitability | 3.8 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 2,2 | 3.1 | |

| Profit margin | 4.7 | 5.2 | 4.1 | na | 2.0 | Data |

| Capital turnover | 2.2 | 5.5 | 3.7 | na; | 1.3 | Data |

| Financial strength | 2.9 | 4.3 | 6.3 | na | 4.6 | Data |

| Ability to use economies of scale | 4.1 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 5.0 | Survey |

| Ability to use economies of scope | 4.3 | 6.1 | 3.8 | 2.7 | 5.0 | Survey |

Fish processing specific inputs

All the countries have rather low scores for fish processing specific inputs. Capacity utilisation is particularly low in Newfoundland and Vietnam, but also poor in Norway and Spain. Iceland has very strong supply and cost of fresh water, with Spain and Norway following and Newfoundland and Vietnam having relatively worse scores, impacting negatively on the country’s competitiveness (Table 15). The Icelandic fish processing sectors financially outperforms the industry in the other four countries with data on this topic.

Table 15 Fish processing specific inputs and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5.1 Capacity utilization | 2.9 | 4.0 | 5,5 | 2,5 | 3,8 | |

| Distribution of the catch within the year | 3.3 | 2.2 | na | na | na | Data |

| Timing of wetfish availability | 2.5 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 3.8 | Survey |

| 2.5.2 Cost items | 5,3 | 6,8 | 5,7 | 4,3 | 3,7 | |

| Cost of electricity | na | na | na | na | na | Data |

| Supply and cost of fresh water - fish processing | 5.3 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 4.3 | 3.7 | Survey |

| 2.5.3 Profitability | 3.7 | 5.9 | 3.9 | na | 3.3 | |

| Profit margin | 3.5 | 5.8 | 3.8 | na | 3.5 | Data |

| Capital turnover | 3.0 | 6.5 | 3.0 | na | 1.2 | Data |

| Financial strength | 5.0 | 5.5 | 5.5 | na | 5.7 | Data |

| Ability to use economies of scale | 4.1 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 1.5 | 5.0 | Survey |

| Ability to use economies of scope | 4.3 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 5.0 | Survey |

Aquaculture specific inputs

As expected, Norway has a clear competitive advantage in aquaculture. The country scores highly in terms of transferability of licenses between firms, costs and profitability, but the impact of regulations on capacity utilisation has a better impact on competitiveness in Spain (Table 16).

Table 16 Aquaculture specific inputs and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.6.1 Property rights | 6.0 | 4.9 | 4.9 | na | 1.3 | |

| Transfers of licenses between firms | 6.0 | 4.9 | 4.9 | na | 1.3 | Survey |

| 2.6.2 Capacity utilization | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.7 | na | 4.8 | |

| Impact of regulations on capacity utilization | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.7 | na | 4.8 | Survey |

| 2.6.2 Cost items | 4,6 | 5,1 | 4,6 | 5,7 | 5,1 | |

| Cost of electricity | na | na | na | na | na | Data |

| Supply and cost of seedstocks | 4.7 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 6.0 | 3.8 | Survey |

| Supply and cost of feed | 4.6 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 5.8 | Survey |

| 2.6.3 Profitability | 5.5 | 1.8 | 2.8 | na | 4.6 | |

| Profit margin | 6.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 | na | 3.7 | Data |

| Capital turnover | 3.8 | 2.9 | 1.9 | na | 6.7 | Data |

| Financial strength | 6.2 | na | 6.5 | na | 4.0 | Data |

| Ability to use economies of scale | 5.3 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 5.3 | Survey |

| Ability to use economies of scope | 4.8 | 4.9 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 5.3 | Survey |

Technological readiness

The level of technology in the harvesting and fish processing sectors is considerably higher in Iceland than in the other four countries, but Norway, Newfoundland and Vietnam all receive high scores for the technology employed in the aquaculture sector (Table 17).

Table 17 Technological readiness and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.8.2 Fisheries technology | 5.4 | 6.3 | 5.5 | 4.1 | 3.3 | |

| Technical level of vessels and mechnical equipment | 6.0 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 3.5 | Survey |

| Fishing technology | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 4.1 | 3.5 | Survey |

| Processing technology on board | 4.8 | 6.6 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 3.0 | Survey |

| 2.8.3 Fish processing technology | 4.1 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 5.0 | |

| General technology - fish processing | 4.1 | 6.6 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 5.0 | Survey |

| 2.8.4 Aquaculture technology | 6.3 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.8 | |

| General technology - aquaculture | 6.3 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.8 | Survey |

Pillar III Innovation and sophistication

This pillar consists of two subsections on business sophistication and R&D innovations. Vietnam received the lowest scores fin both categories (Table 18).

Table 18 Business sophistication and two following aggregation levels of competitiveness

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Innovation and sophistication | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.8 |

| 3.1 Business sophistication | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 3.8 |

| 3.2 R&D Innovation | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 3.7 |

Business sophistication

The level of business sophistication is similar in all the countries except Vietnam (Table 19). Norway is the only country where the industry receives official marketing support.

Table 19 Business sophistication and individual indicators, average score

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 Business sophistication | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 3.8 | |

| Official marketing support - marketing | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | Survey |

| Marketing operations - wild fisheries | 4.9 | 4.3 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 4.0 | Survey |

| Marketing operations - aquaculture products | 5.2 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 3.8 | Survey |

| Competition among major suppliers - fisheries | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 5.3 | Survey |

| Cooperation in the value chain - fisheries | 3.1 | 5.4 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 3.3 | Survey |

| Cooperation in the value chain - fish processing | 3.1 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 2.7 | 3.2 | Survey |

| Competition among major suppliers - fish processing | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 4.3 | Survey |

| Cooperation along the value chain - aquaculture | 5.6 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.4 | Survey |

R&D Innovation

Iceland and Spain have a slight edge in R&D innovation, with Norway and Newfoundland receiving slightly lower scores and Vietnam some distance behind (Table 20).

Table 20 R&D innovation and individual indicators, average scores

| Level | Norw. | Iceland | Spain | Newfld. | Vietnam | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.2 R&D Innovation | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 3.7 | |

| R&D Fishing technology fisheries | 4.6 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 3.5 | Survey |

| R&D Processing technology fisheries | 3.9 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 4.0 | 4.3 | Survey |

| R&D Processing technology fish processing | 4.5 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | Survey |

| R&D - aquaculture equipment | 5.9 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 4.4 | Survey |

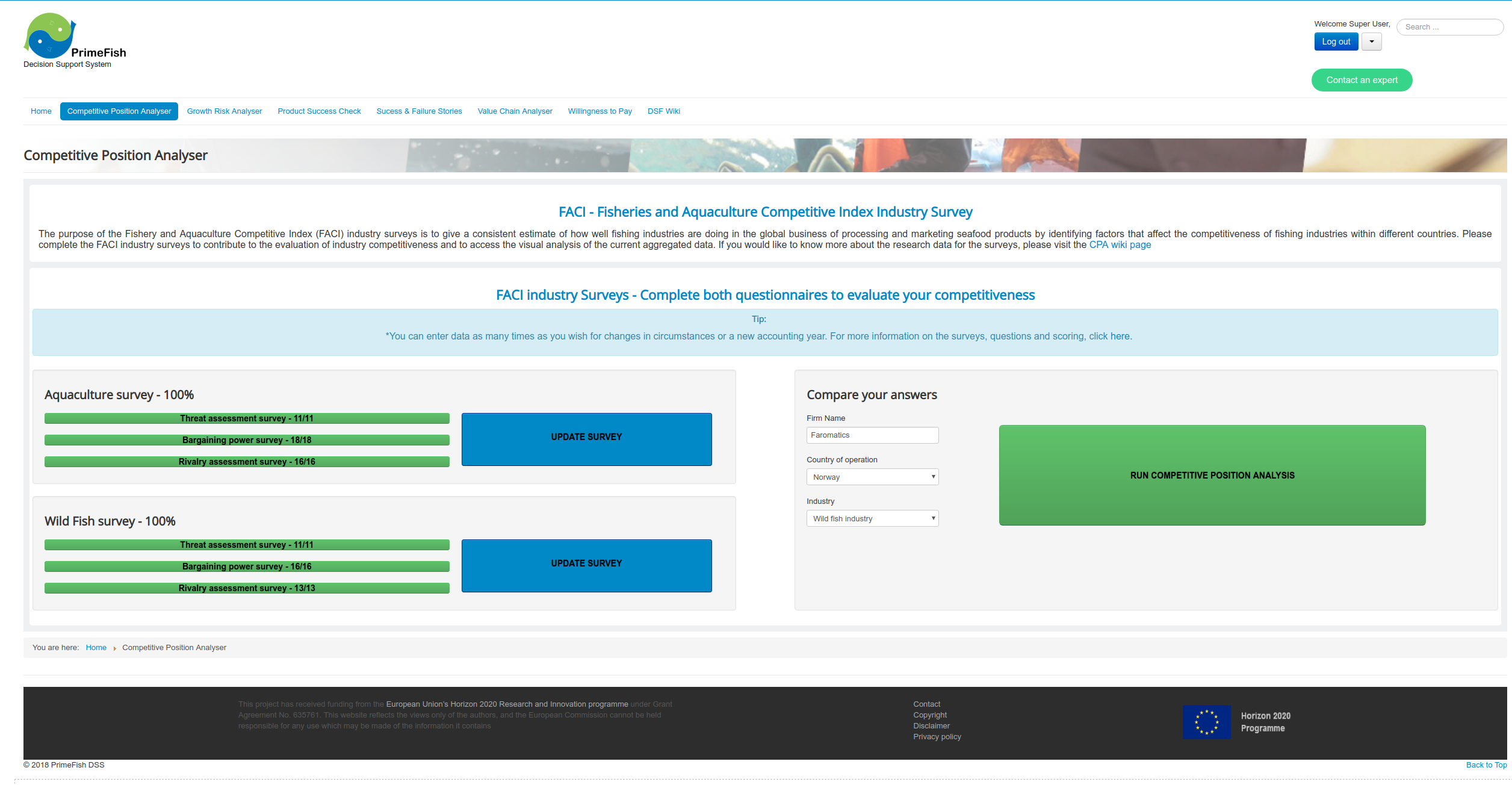

The tool

The | CPA tool is the implementation of the FACI survey both at firm-level and national-level. It can be accessed by clicking the quick access icon for the CPA in the | PrimeFish DSS home page or by clicking the appropriate menu link in the top navigation bar.

CPA home page

In the home page the users can define their company's profile information, including the country, which is used as a parameter to select which values to display as a benchmark when running the CPA tool. If the user selects France as their company's country, the results will be compared against the data collected for France. The user can change the value of any of the input fields in the Company Profile section located in the left side of the home page and click the update button to save the changes.

Right below this section the users can select additional search parameters before running the CPA tool. These parameters will set which industry, species and market data will be shown in the results page. Once the user click the Run CPA tool button, the user will be redirected to the results page where a graphical analysis will be shown. Completion of any survey is not required to run the tool, however any references to user value will be set to zero in the graphical comparison in the results page.

The firm-level survey can be accessed by clicking its respective Update survey button on the right section of the CPA home page, which will redirect the user to the survey page for the chose survey. The surveys are divided in two sections by industry (Aquaculture/Wild fish) and each one is further subdivided into three subsections:

- Threat Assessment Survey

- Bargaining Power Survey

- Rivalry Assessment Survey

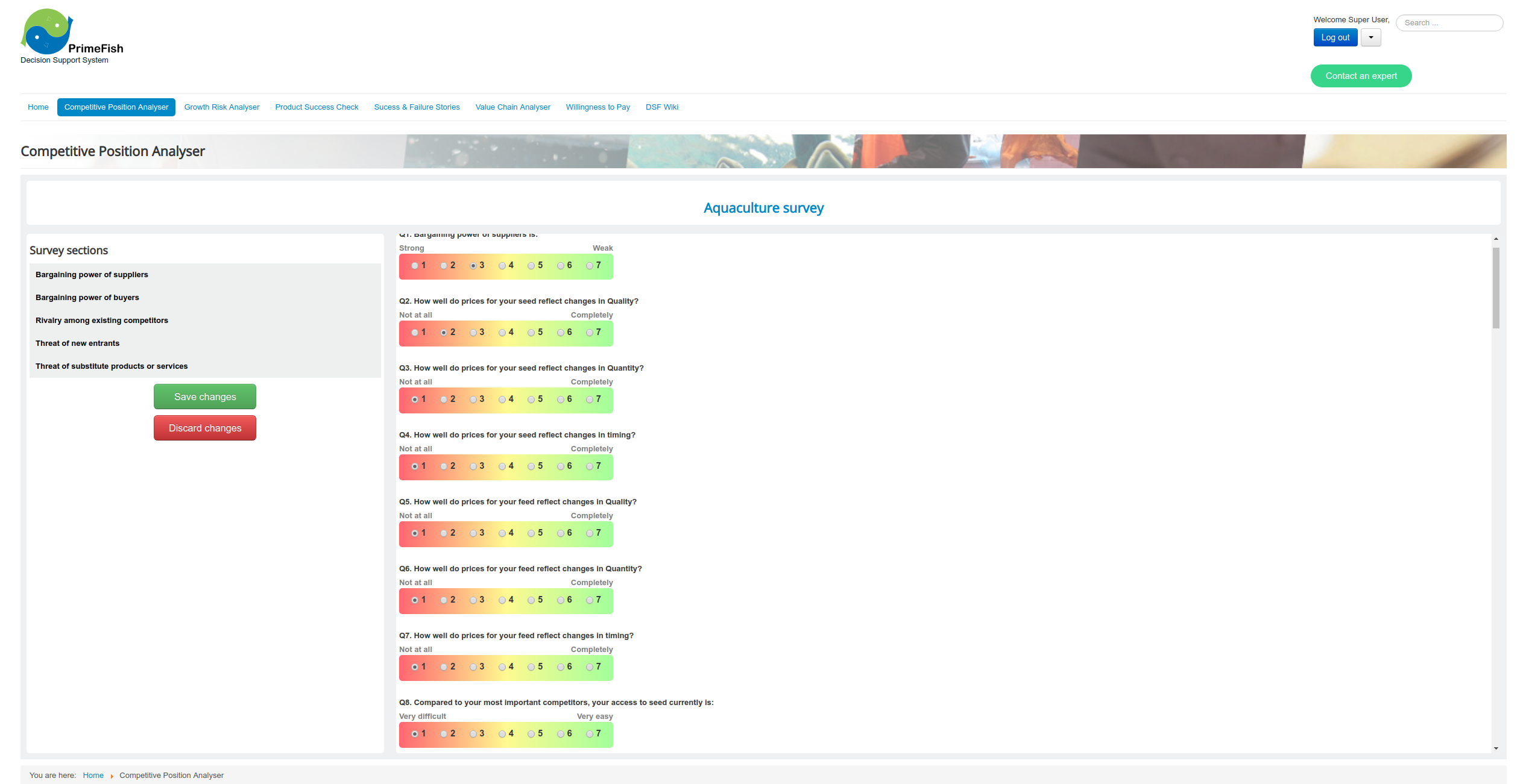

CPA survey pages

After clicking the appropriate button and being redirected to the survey page, the user can then analyse and answer the survey by choosing the answers from the array of possibilities and then choosing to move to the next/previous survey or by returning to the home page. The survey answers are automatically saved as long as the user clicks one of the blue buttons on the bottom page of the current survey page to go to the next/previous survey or to go to the home page. If the users clicks the red Discard changes button, the current changes will not be saved and the user will be redirected to the CPA home page. The answers can be updated at any time and as many times as needed. Once the user is satisfied with his answers he can run the CPA tool by clicking the Run CPA tool button in the home page to get the results relative to their answers. The user can answer as many or as few questions from any survey as he/she wants, and return at any point in time to change their answers. A yellow progress bar for each subsection of the surveys is shown in the CPA home page to let the user know of the progress they made. If no answers have been given for a particular survey subgroup, no progress bar is shown and once the user answers all questions in a survey subgroup, the progress bar will turn green. The more answers the user gives, the more accurate the calculation for the CPA will be.

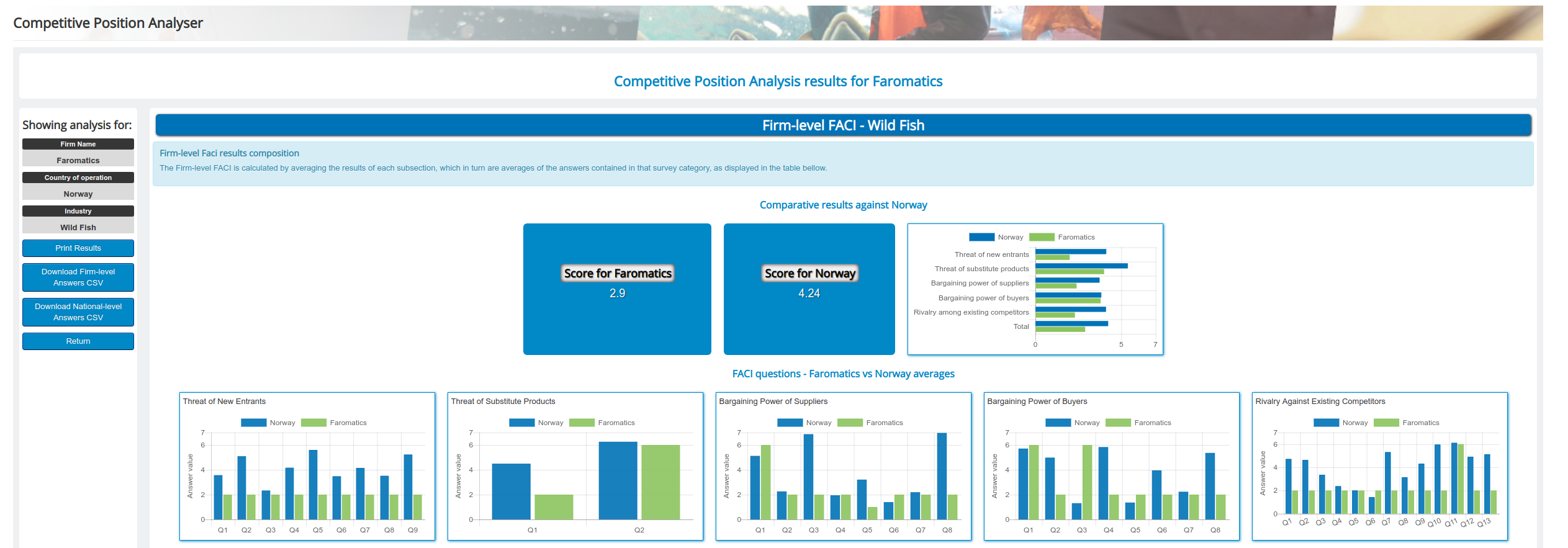

CPA results page

When the user clicks the Run CPA tool button, the results page will first display the user's FACI score, with details about their average score in each section and also detailed comparative scores for each answered question.