Deliverable 3.4

Contents

- 1 Deliverable D3.4 - Report on evaluation of industry dynamics opportunities and threats to industry

- 1.1 Executive Summary

- 1.2 Atlantic cod

- 1.2.1 Summary

- 1.2.2 Global Market review

- 1.2.3 Fisheries Management System in Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland

- 1.2.4 Market approach

- 1.2.5 Processing

- 1.2.6 Price settling mechanism

- 1.2.7 Fishing

- 1.2.8 Consolidation in the sector

- 1.2.9 Overall economic performance and competitiveness of the fisheries value chain

- 1.2.10 Strategic Positioning Briefing

- 1.3 Atlantic Herring

- 1.4 Salmon

- 1.5 Rainbow trout

- 1.6 Sea bass & bream

- 1.7 Pangasius

- 1.8 Bibliography

Deliverable D3.4 - Report on evaluation of industry dynamics opportunities and threats to industry

Executive Summary

In this report, evaluation of industry dynamics opportunities and threats to industry, we are focusing on value chain dynamic for certain industries and species. The framework used is a bit different for caught species (cod and herring) and farmed species (salmonoids, sea bream & bass and pangasius). The industry dynamics is more value chain focused for the caught species, while individual companies are also the focus for the farmed species. The main results for the caught species reviled very interesting structural difference and functionality of the value chains for cod between Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland. Previous studies have argued that the superior harvesting and marketing strategies of the Icelandic industry may be rooted in factor conditions that are difficult to duplicate and a rigid institutional framework in Norway and partly the social resource structure of the Newfoundland industry, where market conditions have very limited consideration in terms of the structure or management of the industry.

The vertically integrated companies in Iceland where the processor owns its own fishing vessels. Unlike the push supply chain system followed by the Norwegian and partly the Newfoundland companies where they must process the fish that they receive, the Icelandic processors places orders to its fishing vessels based on the customer orders and quota status, thus following a pull supply chain system. The Icelandic processors are able to sends orders to the vessels for how much fish of each main spices is wanted, where to catch and to land so they have the desired size and quality of raw material needed for fulfilling customer orders. This structural difference is also affecting the product mix that the countries are going for.

It is also very interesting to see the difference in structure and functionality of the value chains between Norway, Iceland, Denmark and Newfoundland for herring. The structure of the industries is different as seen in the degree of vertical integration and the limits that government’s put on the industries. It is though surprising how homogeneous the industry is between those nations. The nature of pelagic species that is, seasonality and high catch volumes in short periods, makes the product global commodity for further processing from one season to the next. The main markets are Business to Business (B2B)

The first noticeable difference observed, apart from the structure, is the price settling mechanism. On one hand it is the Norwegian system that builds on minimum price and auction market which is the same that is used to determine the Danish price. In Iceland the price is decided by the Official Bureau of Ex- Vessel Fish Prices. he Norwegian price is in many cases double that of the price in Iceland. The price obviously affects the profitability of the industry as the Norwegian fishing is benefiting from high price but the processing sector is suffering from low profitability. On the other hand, the processing sector in Iceland is doing well as well as the profitability of the fishing is healthy. It can be claimed that the overall profitability is higher in Iceland due to the freedom of strategically positioning yourself in the value chain and being vertical integrated or not, without external limitation as those that can been seen in Norway, Denmark and Newfoundland

Aquaculture is the primary source of salmonid supply globally. The different salmonid species available on the market are substitutable to a considerable extent due to their pink flesh colour and similar properties. However, different dynamics in the broader competitive environment, and in the particular circumstances of national sectors, in which the businesses comprising these industries are embedded, have determined different developmental trajectories for the very same industries. These dynamics include the changing nature of consumer demand characteristics, production technology, national regulatory regimes, international trade, industry structure, availability of natural resources. Discussed in this chapter are the cases of farmed Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout in major producer countries and the role key external influences have played in shaping different developmental outcomes. The interaction of selected salmonid producer firms with their distinct competitive environments is illustrated through firm-level case studies of strategic positioning.

The output of most salmonid aquaculture, and Atlantic salmon in particular, is highly commoditised i.e. there is little differentiation between farms and competition is based purely on price. These products, mostly head-on gutted fresh fish, serve as raw material for further processing. In that situation, large enterprises which can reduce costs of production economies of scale and offer the lowest price, would have competitive advantage.

Seabass and seabream are the most important species for the aquaculture of fish in Spain, being one of the most important markets in Europe. The production and the market is highly concentrated and economies of scale may improve the competitiveness of the sector. The integration of production and the stable international trade allows to increase the share of the price value. The pangasius industry in Viet Nam has grown quickly over the last two decades to become one of the main food exports from the country and a major contributor to the Vietnamese economy. Pangasius products, mainly frozen fillets, are currently exported all over the world, with the largest markets being the EU, the USA, and more recently China. The success in market penetration of pangasius products can be attributed to their mild taste, lack of bones, and most importantly their low price compared to other, more traditional whitefish products, for which it acts as a low-cost substitute.

The production node in the pangasius’s value chain was initially highly fragmented, composed of many small-scale family owned enterprises and middle-scale processor-exporters. However, the industry is undergoing a rapid a rapid consolidation and increasingly being served by large-scale vertically integrated enterprises, encompassing all stages of the value chain. The reasons for that can be found in the improvement in seed production methods, control of fish health and disease problems, feed and nutrition and market requirements.

Atlantic cod

Summary

It is very interesting to see the difference in structure and functionality of the value chains between Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland. Previous studies have argued that the superior harvesting and marketing strategies of the Icelandic industry may be rooted in factor conditions that are difficult to duplicate and a rigid institutional framework in Norway and partly the social resource structure of the Newfoundland industry, where market conditions have very limited consideration in terms of the structure or management of the industry.

The vertically integrated companies in Iceland where the processor owns its own fishing vessels. Unlike the push supply chain system followed by the Norwegian and partly the Newfoundland companies where they must process the fish that they receive, the Icelandic processors places orders to its fishing vessels based on the customer orders and quota status, thus following a pull supply chain system. The Icelandic processors are able to sends orders to the vessels for how much fish of each main spices is wanted, where to catch and to land so they have the desired size and quality of raw material needed for fulfilling customer orders.

This structural difference is also affecting the product mix that the countries are going for. Iceland is therefore placing more and more emphasis on fresh fillets and pieces, while the other countries are going for more traditional products, like salted, dried and frozen products. Due to the vertical integration in Iceland, the production plans are developed based on customer orders and then a plan is made for fishing, while in Norway and Newfoundland, the production plans is usually developed after receiving the fish at the processing plant as the information about volumes of specifies caught and quality is not available beforehand.

Global Market review

According to a book by Mark Kurlansky; ”Cod - A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World”. Cod was the reason Europeans set sail across the Atlantic, and it is the only reason they could. What did the Vikings eat in icy Greenland and on the five expeditions to America recorded in the Icelandic sagas? Cod, dried in the frosty air. What was the staple of the medieval diet? Cod again, sold salted by the Basques. As it turns out, cod has sparked wars, shaped international political discourse, impacted diverse cultures, markets, and the environment.

Cod importance has dwindled, but it is still of major importance to Iceland and Norway and growing importance in Newfoundland and therefore it is important to look at industry and market dynamics, opportunities and threats in the value chain of cod for these countries.

Main producers

Atlantic cod is only one of many species entering the global supply chain for whitefish, which can be viewed as substitutes. Amongst them, we find Alaska pollock, hake, saithe, Pacific cod, haddock, hoki and Atlantic redfish. Altogether, the global supply of these species in 2015 was about 6,937 million tonnes, according to FAO. The largest species by far is Alaska Pollock, for which the catch in 2015 added up to 3.3 billion tonnes – 48 per cent of the total whitefish supply – for which US and Russia are the largest actors.

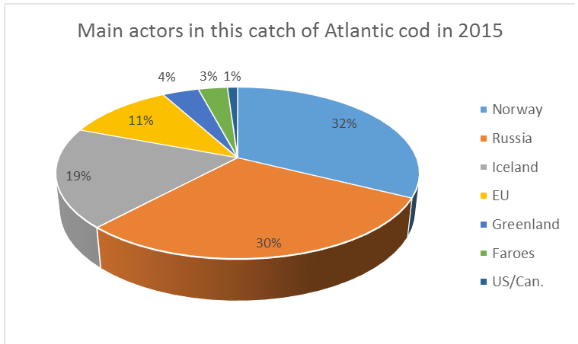

Atlantic cod was the second largest species in the global whitefish supply in 2015, responsible for 1,304 million tonnes, or 19 per cent of the total. The main actors in this catch of Atlantic cod in 2015 was Norway, Russia, Iceland and the EU with 11% of the catches as can been seen in figure 1. The main actors among the EU countries are Denmark, UK, Germany and Poland. The main suppliers since the turn of the century are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Main actors catching Atlantic cod in 2015 according to FAO

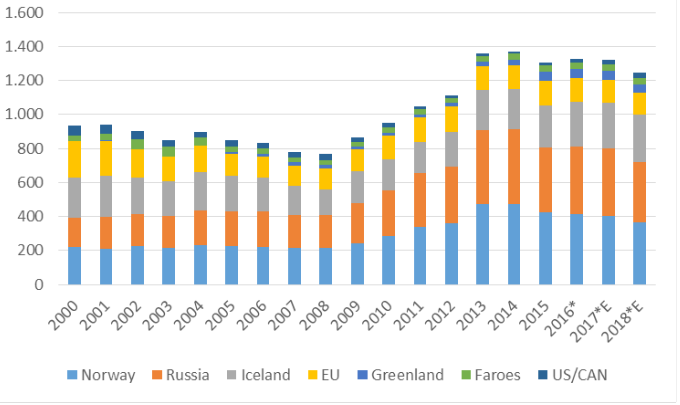

Figure 2. Supply of Atlantic cod from the North Atlantic waters, by country, 1000 tonnes, 2000–2018. Source: FAO and (*) Groundfish Forum

FIgure 2 shows a relatively stable distribution of cod catches until the increase in the quotas for Northeast Atlantic cod about 2009, where Norway and Russia increased their share. Moreover, it shows that the catch of US/CAN fell until the end of this period, when it rose again, and that Greenland catches have increased over the period. As can been seen in Figure 2, The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) has recommended a 20 percent cut in the Barents Sea cod quota for 2018. However, the Joint Russian Federation- Norwegian Fisheries Commission in October 2017 agreed on the 2018 quotas, which include a 13 percent cut in the Barents Sea cod quota to 775.000 tonnes (FAO).

Main markets

The EU is by far the largest market for cod products in the world. Cod is processed in different format to fulfil the needs and customs of different markets. There is a big consumption of fresh and frozen product in EU, especially in UK and France. The tradition of drying fish to preserve it dates back to Viking times, but the process of salting fish began in the 15th century, when the Iberian fishermen were sailing to and from Newfoundland. Cod that had been preserved in salt would last the length of the journey. Clipfish/saltfish or bacalao is also popular in Catholic countries, thanks to a tradition that dates back to the middle ages when the pope ordered Catholics to eat fish instead of meat during Lent. Therefore have Iceland and Norway exported bacalao for centuries to Catholics around the world, especially to Spain and Portugal. There are also number of other traditional markets, like Nigeria for dried fish parts and heads. USA was also a big market for cod products, and it has been growing again in recent years, especially for fresh cod.

Cod producers from Norway have been taking putting effort in emerging market like China, where there is great potential but no custom of consuming cod products.

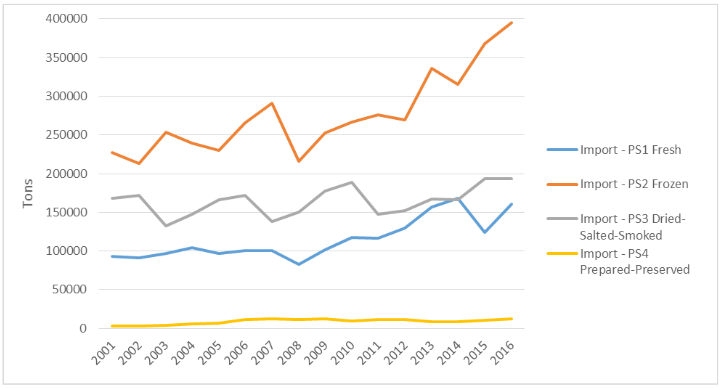

Figure 3. Trade of cod in the EU, Import of cod products in the EU, both extra and intra EU trade. Raw data from EUMOFA.

The total import in the EU was 761 thousand tons in 2016 and the imports in total have been on the rise in recent years. That don’t mean that this came all from outside of EU. Part of the imports (42.1%) came from Intra EU trade while the larger part (57.9%) came into the EU from countries outside the EU, like Norway and Iceland. Largest part of the EU export figures of 421 thousand tons are Intra EU trade or 94.1%, therefore there are only around 25 thousand tons of cod exported out of the EU to non EU countries.

Frozen cod is by far the most common preservation form of traded cod in the EU as can been seen in Error: Reference source not found. The import of dried, salted and smoked cod products have been relatively stable in recent years but the main growth has been in the import of frozen and fresh cod products. The imports of fresh cod has been on the rice since 2008, but 2015 the volume went down but gained momentum again in 2016. The imports of prepared or preserved products is low but relatively stable between years.

Fisheries Management System in Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland

General

Norway

“The main objective for the industrial and fisheries policy is the highest possible value creation in Norwegian economy, within sustainable limits. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries work is to obtain this main objective builds on the following sub- objectives: efficient use of society’s resources, increased innovation and adaptation ability, and companies who succeed in international market. The sub-objectives and prioritised areas to achieve these are just as important for the seafood industry as other activities in Norway. A purposeful superior effort to stimulate to increased innovation and adaptation ability in Norwegian economy is of great importance also for the seafood industry.”

Iceland

Iceland seafood sector is modern and competitive, based on sustainable harvest and protection of the marine ecosystem. Marine products have historically been the country’s leading export items and the seafood industry remains the backbone of the economy. The fisheries management in Iceland is primarily based on extensive research on the fish stocks and the marine ecosystem and biodiversity, and decisions on allowable catches are made on the basis of scientific advice from the Icelandic Marine Research Institute and catches are monitored and enforced by the Directorate of Fisheries.

Newfoundland

Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is responsible for management of the Canadian fisheries stocks in accordance with the roles and responsibilities outlined in Canada’s Fisheries Act. The major objectives and priorities of the DFO’s fisheries management policies include ensuring environmental sustainability and conversation of the resource, ensuring access based on adjacency or proximity to the resources, consideration of the relative dependence of coastal communities and the dependence of various fleet sectors, as well as factors such as economic efficiency and fleet mobility. Inclusion of stakeholders in the decision-making process is regarded as a key priority for fisheries management in Canada (Fisheries Management Decisions, 2017; Sustainable Fisheries Framework, 2017).

Quota system: Individually Transferable Access

Norway

- Rule of thumb: Off-shore vessels governed by licenses, and coastal vessels by annual

participation rights (off-shore conventional vessels excepted).

- In order to get a fishing quota you have to buy a vessel (a pre- requisite is loosened up in later

years, where one nowadays can get hold of structured quotas, without factual vessel transactions). Transferability has increased, buts still with great imperfections compared with an ITQ-regime.

- Quota distribution to vessel groups (coastal vs. off-shore, and different size classes within

the coastal vessel group) based on allocation formulas agreed within the Norwegian Fishermen Association, upon historical rights. Still with some autonomy for the authorities to allocate certain shares of quotas to special schemes (youth, recruitment, R&D, etc.) before allocation to vessels.

- Regional distribution safeguarded by fleet composition, and limited transferability between regions

for some licenses/participation rights.

- Quota year is the same as the almanac year.

Iceland

The ownership of quotas involves the right to catch the fish but does not entail ownership of the fish stock. Thus, it is claimed that the quota does not mean the ownership of the fish but rather the right to catch the fish. Since 2001 small boats has been allocated TAC (Total allowable catches) and all effort based system abolished until 2009 when coastal fisheries was introduced. As can be seen in figure the share of small boats of the TAC was 14.2% in 1992 and is 22.3% in 2016. It peaked in 2001 when it was 24.1% of the TAC in cod. Part of this increase can be explained with changes in classification of small boats as in 2013 when small boat definition went from 15 gross registered tonnes (GRT) to 30 GRT.

- The emphasis of the fisheries management system since 2001 has been to simplify the system and bring all into the quota

system of ITQ and TAC system. Against this, open access fishing was introduced in 2009 when new system was introduced for small boat called costal fishing (isl. strandveiði).

- By the 1990 Act the fishing year was set from 1. September to 31. August in the following year but previously

it had been based on the calendar year. This was an effort to channel fishing of the groundfish stocks away from the summer months, when quality suffers more quickly and many regular factory workers are on vacation.

Newfoundland

Generally, DFO allocates quotas for each stock/species (or group of species) in accordance with a specific fishing season and within a specified fisheries management division. The key regions or fisheries management divisions for cod quota or allocation in NL are:

- 3K (including 2J3KL)

- 3Ps

- 4R (including 4R3Pn)

Information included in a fisheries decision may include:

- opening and closing dates for the season,

- total allowable catches (TAC),

- and management plans (Fisheries Management Plans, 2017) with certain fisheries managed through multi-year Integrated Fisheries

Management Plans (Integrated Fisheries Management Plans, 2017). In Newfoundland, Atlantic cod are managed through a series of strategies. Pending the NAFO region, the cod fishery can be a set quota, a weekly allowance or allocation, or may be an experimental fishery. Based on principles of adjacency and the numbers of vessels /harvesters participating in the fishery, the coastal fleet (<65 feet) has a strong position within the NL fisheries sector.

Entry barriers into the system:

Norway

The activity demand in the Participation Act states that in order to own a fishing vessel one have to be an active fisher.

- Many exceptions have been granted. Firstly, on the same footing as active fishers are administrative fishing vessel

owners – caretaking the daily operation of vessels from land. Also, as the filleting industry in the north of Norway was built up and prioritised as whole year employers, many filleting firms were granted cod trawl licenses, which today are held by two big processing concerns (Lerøy and Nergård)

- To become a registered fisher, you have to live in Norway and work on a registered Norwegian fishing vessel

- To get a vessel registered a as a fishing vessels, demands have to be met regarding size class and operating areas.

Like in other western society fisheries, the closure of the commons have increased the capital intensity, and labour is to a large degree substituted by capital intensive production equipment. Foreigners can buy vessels below 15 meters in Norway and control no more than 40 per cent for boats above 15 metres. Processing industry - no nationality limitations exists

Iceland

All professional fishing in Iceland has to have licences for fishing.

- Capital intensive due to high price of quota

- Entry for foreign investments very limited (or closed).

- Economics of size Costal fisheries

- In 2016 total 9790 thousand tones are allocated for coastal fishing one open access base from May to August.

- Open access

- Low profitability (returning loss for all years of operation)

- Coastal fishing is limited to small boats with maximum two handlines per person and

maximum two person on the boat. The maximum 650 kg catch per day and fishing is limited to four days a week.

- There are also limits of TAC for each area for the small

boats.

Newfoundland

No new licences being issued by DFO

- Entry into fishery is based on acquisition of existing licences

- Requires a professional fish harvester certification

- Significant investment in terms of education and training and at-sea experience

- Cost of entry into the fishery is prohibitive due to the high cost of capital investment (vessels,

gear, etc.) and the cost of licences

- Uncertainty over future allocation/quotas and if there will be return on investment

Exit barriers from the industry

Norway

- Exit barriers are fewer Vessel owners are unable to recover the full vessel value as they exit the industry.

- However, the increase in quota prices over the years should cover for such discrepancies.

- Limited transferability between regions in some vessel groups.

Iceland

- Low exit barriers quota easily sold and market open

- No tax limitation for selling the fishing rights and ITQ.

- Unlimited transferability between regions

Newfoundland

- Low exit barriers licenses are easily sold; open market for licence

- No regulations governing the sales

- Exit not linked to potential resource re-allocation for new entrants; i.e. portion of

share or allocation is not reinvested back into the fishery

- No financial reinvestment (e.g.no tax or fee) required to be paid by harvester upon

sale of licence and exit from the system

Quota ownership and quota prices

Norway

There is in Norway a consolidation limit for cod for both conventional off-shore vessels (auto-liners) and cod trawlers, but not for coastal vessels.

- Firms owning conventional off-shore vessels cannot, directly or indirectly, own vessels that

control more than 15 per cent of the group quota for any of the species included.

- For cod trawler, firms cannot control more vessels exceeding more than the number that

controls 12 quota factors. With today’s quota ceiling (maximum four quota factors per vessel), it means 3 full structured vessels and about 13 per cent of the group quota for cod trawlers.

- However, there are specific rules for ship owners that also own

processing facilities, which is the reason that the two before mentioned cod trawler ship owners have more vessels than the limit of the Act. Quotas can be transferred among vessels in a vessel owning company, but only upon authorities’ approval. Also, other eases of transferability exist (renting quotas, ship wrecking, replacement permit – in awaiting of new vessel, and others) A quota flexibility between years is also possible, but within the cod fishery, this is only possible on group level – not for individual vessels. An overfishing of the vessel groups’ cod quota one year will be claimed against next year’s quota, and vice versa if the full quota is not taken. For the vessel groups with a limited number of vessels, this individual vessel quota flexibility between years will be effectuated over the turn of the year from 2017 to 2018. Coastal vessels will have to wait longer until this can be effectuated, since so many extraordinary schemes exists for these vessels Quotas within Norwegian fisheries are transferable, but there exists no central brokerage system where quota prices are noted.

Iceland

Limitation on consolidation of quota ownership – max 12% ownership of TAC for each species.

- Quota is bound to fishing vessel but companies with number of vessels can transfer quota between vessels.

- 15% of TAC can be transferred between years by companies

- 5% can be overfished in the fishing year and will then be withdraw from the companies next year TAC

TAC cannot be transferred between systems, example from the hook system to the general TAC system

- There is regional restriction to fishing in the coastal fisheries

- The fishing ground is split into 4 areas

Newfoundland

Transferability allocation of quota/weekly

- Limit on combining (maximum set at 2:1 or 3:1) shares or allocation for inshore fleet

- Transfer of shares/allocation between vessels is permanent (inshore fleet);

- Larger offshore vessels can transfer quota between vessels annually- it is not permanent

- Opportunity to buddy-up is limited or restricted based on region and season

Possibilities to upgrade in the system

Norway

Upgrading is possible, but is capital intensive. Opposite to the fishing industry, no license is needed to erect processing capacity. Upstream vertical integration (towards the fishing fleet) is prohibited, while downstream (from fleet to processing) allowed. Less cod in onboard processed in the off-shore over time, but more is sold as frozen HG.

Iceland

Limitation to move between systems

- hook system is looked in there but can be transferred inside that system

- Small boats can enter the costal fisheries even if they are operating in other systems.

- only requirement’s is during that time they only operate in costal fisheries.

Newfoundland

- Limited opportunity for vertical integration based on PIICAF and allocation of first 115,000

tonnes to inshore sector

- Upgrading is based on number of licences purchased

Management measurements

Norway

Landing obligations are not a subject in Norwegian fisheries, since it is mandatory to land all caught fish. Delivery obligations have nevertheless been put on about half the cod trawlers in order to see to it that fish is landed where it was supposed to, in the cases where processing firms were granted cod trawler licenses but where ownership to trawlers have been dissolve during the years. No limits exists to how much a vessel can land on a daily basis.

- safety limits to how much cargo a vessel can hold, and

- also a general rule that “a vessel should not carry more than it can take care of in a reasonable manner”,

- but no limits exist as to what is the limit for daily catches in order to enable a best possible raw material quality.

Iceland

Landing obligation

- None, except in coastal fisheries the fish has to be landed before 16:00 and in harbours in the fishing zone

- Delivery obligations are not in place in Iceland and no processing requirements

Fishing days – regulations/number of days

- Coastal fisheries have limitation (4 days pr. week/4 months)

- Gear restriction in the hook system

Quantity

- In the coastal fisheries system

- Max 650 kg pr. day/14 hours pr day

- TAC for each area

Closures

- Marine Institute has licences to introduce closures fishing areas if for example share of small fish

is too high according to landing or historical landing data Discard ban

- There are measurement’s in place to avoid discard

- Limited withdraw on unwanted catch form TAC

- Up to 5% of fish that is damage can be landed as VS fish special weighted and not withdraw from TAC

Newfoundland

Landing obligation

- must land all catch unless a species exemption is received from DFO

Minimum processing requirement

- cannot process at sea

Fishing season

- determined annually; reportedly based on ease of access to the fishery and not linked to market conditions

Gear restriction

- in place (e.g. fixed versus mobile gear)

Market approach

Differences in exports

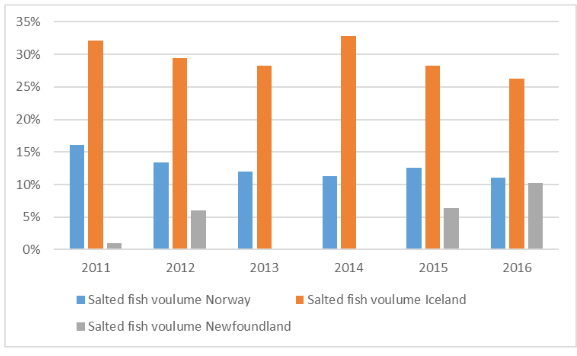

It is interesting to look at the nature of the export from each of the value chains; that is whole fish, fillets, salted products and dried fish.

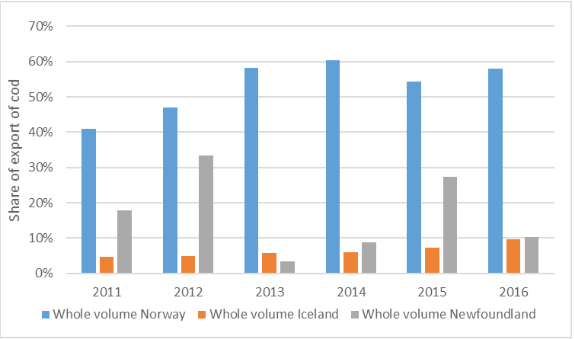

Figure 4. Export of whole unprocessed fish from Norway and Iceland as share of total exports.

- Export of whole fish from Norway has rather been increasing in the recent

years. Part of that could be the increase in catch in Norway or from around 215.000 thousand tons in 2008 to 422 thousand tons in 2015. This export is both frozen H/G (headed and gutted) and fresh.

- Norwegian have focused a lot the last year of marketing their H/G fresh

fish as Skrei where they select the best fish for export under the brand name Skrei and receive premium for that export.

- Export from Iceland has been increasing slightly and is mainly fresh with

head on and is up to 9.7% in 2016 from 4.1% in 2011.

- Newfoundland export of whole fish fluctuates a lot between years;

somewhat determined by the fluctuating TAC and weekly allocation/permissible catch rates. Another way to look at the processing stage of the value chain is to look at the share of fillets in the export from those countries. In figure 3, all filletsexport is summarized. This takes into account whole fillets, fillets portions and fillets from different processing; fresh, frozen and dried.

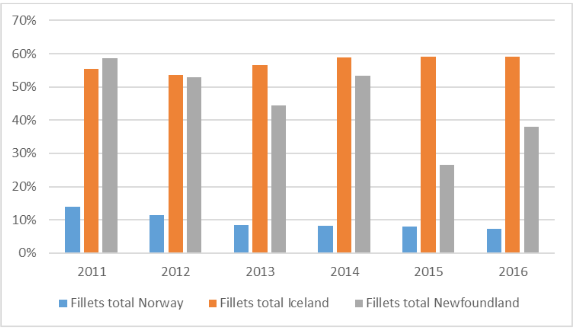

Figure 5. Total share of volume of fillets in export from Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland.

- Fillets production is very limited in Norway and accounts for less than 10%

of the export in 2016 and the share has been decreasing. The fillets production is mainly frozen in Norway.

- Iceland Fillet production is stable from around 55% to almost 60% of the

total export. The 12.1 % of the export are fresh fillets or fillet parts, 21% is frozen and 10.3% are salted both frozen lightly salted and as salted fillets.

- Newfoundland export of fillets fluctuates between years.

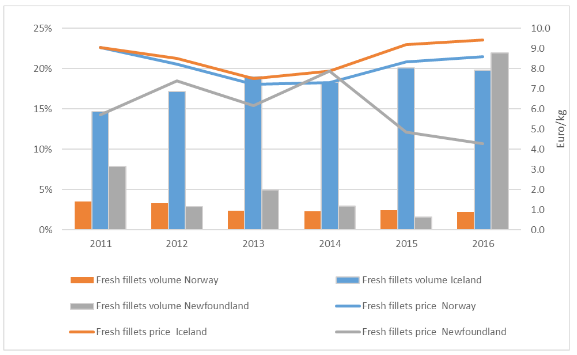

The most valuable fillets production is the fresh fillets or fillet portions. In Figure 6 the fresh fish fillet export is expressed with export value per kg of fillets exported

Figure 6. Share of export for fresh fillets by volume and average export price.

- The volume of fresh fillets as a share of the total export in Norway has

been decreasing in share although the real quantity has not been reduced as the share as quantity of landed cod has increased considerable in this period. It is interesting that the price per kg of exported fillets are lower than for Icelandic fillets, which could suggest more export of whole fillets instead of fillet portions (loin cut) export from Iceland or lower price in the market.

- The export of fresh fillets has been increasing it share in Iceland as well as

price per kg which can mainly be traced to higher degree of portioning in Iceland today due to water jet cutting in the processing part of the value chain.

- The share of fresh fillets in Newfoundland was decreasing from 2011 when

it was 10.1% to 2015 when it was 1.5%. Then in 2016 it was up to 22% of the total export. Price of the export is in most cases (except 2014) much lower than fresh fillets from Norway and Iceland.

Figure 7. Share of export for frozen fillets by volume and average export price.

- The share of the Norwegian frozen fillets export is decreasing or from

around 6% in 2011 to 2.9% in 2016. What is interesting is that the Norwegian receive higher price per kg of fillet than Iceland. One reason for this could the focus of fresh fillet portions (loin cut) in Iceland leaving the tail and belly flap behind less valuable part of the fillet.

- Newfoundland have just under 30% of their export in frozen fillet and the

price is in between Iceland and Norway except for 2013 when they receive the highest price of the three nations. The traditional markets of cod from all the three countries is the salted fish markets mainly in the Mediterranean countries.

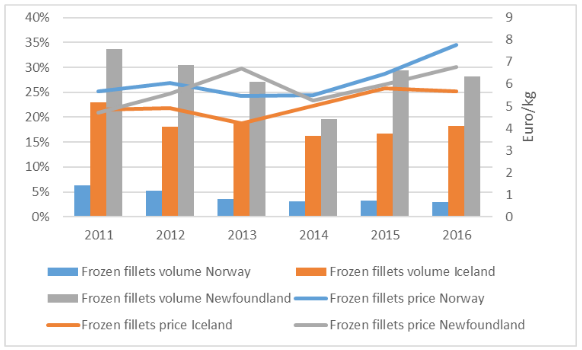

Figure 8. Total share of volume of salted fish in export from Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland

- Salt fish export form Iceland is divided between fillets and split fish. The

share of export of split fish has been decreasing and the share of fillets increasing.

- The Norwegian export is mainly spited fish or clipfish dried salted that is

counted as dried fish.

- The NL export consists of cod fillets dried and salted in brine (with/out

smoking) and wet salted

The export of dried fish is also important for Norway and Iceland but not for the Newfoundland cod. The total share of salted and/or dried fish for NL has decreased over time. Between the years 2005-2010, NL salt fish exports ranged from 8-37% of total exports. This decreased from 2011-2016 where exports varied from 0% to 8.5%

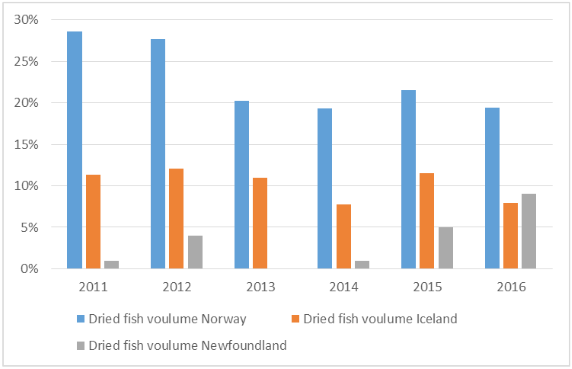

Figure 9. Total share of volume of dried fish in export from Norway and Iceland

- The export of dried fish from Iceland is mostly dried head and frames.

- The Norwegian export is stock fish. The main markets is Italy, which

Norwegian have overtaken almost completely.

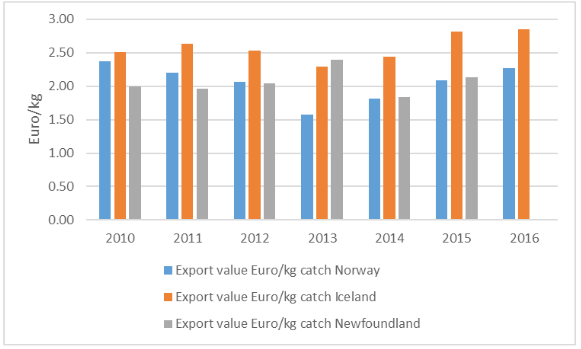

To summarise the marketing and production part together, it is interesting to look at how much value each of the value chains are returning for per kilo of cod. From Figure 10 it can been seen that from 2010, Iceland has in most cases been returning highest value per kg of cod.

Figure 10 Total value of export per kg of cod landed

- This method of calculating value creation does not take into account stock

in the beginning of the year or at the end of the year. So that could affect the numbers especially in Newfoundland that focuses on frozen products.

Summary of main influencing factors regarding market approach

| Factor | Iceland | Norway | Newfoundland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree of processing | Focus on:

|

Raw material exporters.

Focus on:

|

Focus on:

|

| Marketing | Limited mainly based on individual companies | Medium, based on central focus of Norges rafisklag and individual companies.

Producers and fisherman pays fee for marketing of Norwegian seafood |

Limited or based on individual companies |

| Risk in marketing | Rather high. Depend on rather few countries. 94% of the export goes to 10 counties | Medium. Emphasis on marketing and selling to many countries. 86% of exports go the 10 countries | High, Depend on few countries |

Processing

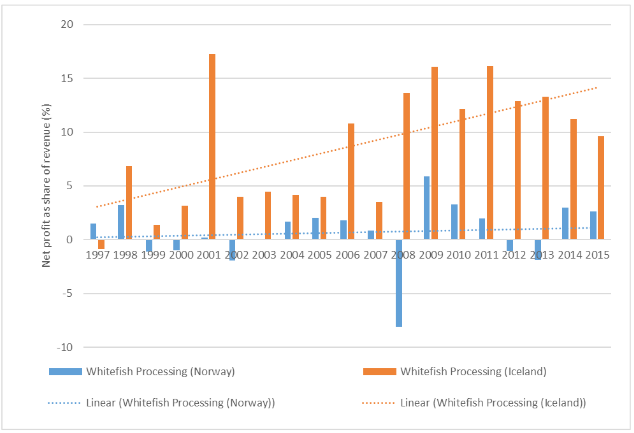

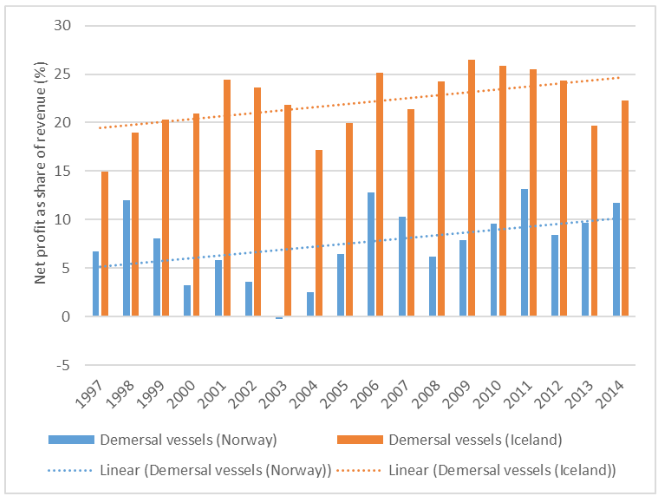

Profitability and performance

Looking at the profitability of the processing sector as a whole as net profit as a share of revenue it is clear that the Norwegian industry is behind the Icelandic processing sector regarding these criteria. The trend line for profit for the processing sector is but much steeper in for the Icelandic sector than for the Norwegian one. The Norwegian processing sector has been suffering from low profitability in recent years. Information about profitability is not available from Newfoundland.

Figure 11. Net profit as share of revenue (Profitability) for the processing sectors in Norway and Iceland 1997-2015.

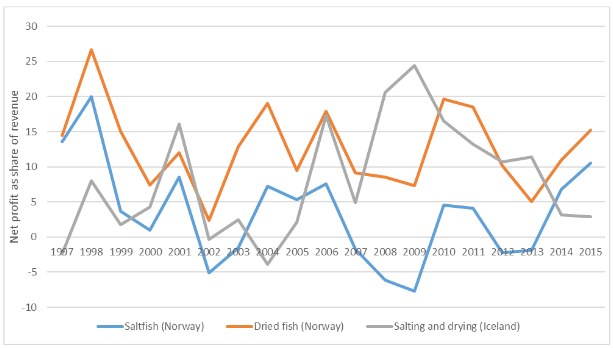

It is interesting to look at the difference in performance for the salting and drying sectors between Iceland and Norway.

Figure 12 Net profit as share of revenue in salting and drying processing sectors in Norway and Iceland 1997-2015

Main issues:

- The best profit in Norway is in dried stockfish and clipfish, that is dried

salted fish. Salting and drying in Iceland is mainly salt fish. Light salted and even light salted and frozen. Profitability is much higher than in salted production in Norway, where production is mainly traditionally salted fish.

- Stockfish production in Norway is returning healthy EBIT for most year. The

stockfish production is aimed for high end niche markets in Italy and lower value markets in Nigeria.

- Drying of whole fish is very limited, the main product of the drying sector

in Iceland are heads and bone frames.

Figure 13. Net profit as share of revenue in filleting processing in Norway and frozen production in Iceland 1997-2015

- Compering export and profitability on fillets production it is possible to

compare the frozen production in Iceland with the filleting production in Norway. The frozen products from Iceland are mainly fillets or fillets portions. It is obvious that there is great difference in profitability although the profitability in Norway has been improving since 2008. One of the influencing factor on the performance of the processing industry is the flow of fish to the processing part. It is interesting to see the distribution of catches for Norway and Iceland as is done in Figure 14, were the flow is shown as monthly share of total catches for the year vs. export price of fresh fillets for these countries in 2014.

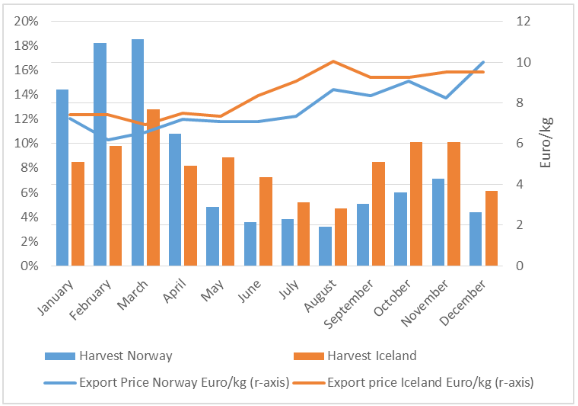

Figure 14. Monthly catches of cod as share of total catches for 2014 and export price in Euro per kg for fresh fillets.

- Norway has around 62.1% of the total catch landed in the first four months

of the year while in Iceland the 39.2% of the total catch is caught during that period.

- During the first four months the price is lower than in the rest of the year

and Iceland receives higher prices every month, except in December.

By-products

Product export statistic from the countries are not comparable making it difficult to estimate the utilisation of the cod. However, the availability and the critical mass needed for creative usage of by-products is always facilitated by the size of processing facilities and level of automation.5.3 Summary of main influencing factors regarding processing

Summary of main influencing factors regarding processing

| Factor | Iceland | Norway | Newfoundland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profitability | High | Low | Undetermined |

| Degree of processing | Medium/fillets | Low | Medium/fillets/frozen |

| Flow of raw material | Stable controlled by the processing marketing needs | Seasonal controlled by the catch and seasons | Seasonal controlled by catch limits (weekly limits may vary within

the same season) and fisherman’s willingness to sell to processing companies |

| Structure of the industry | Vertical integrations | Ban or limits to vertical integrations | Limited vertical integration; Regulations in place to limit

increase in vertical integration |

| Vertical integrations | High | Low | Low |

| Flow of raw material | Stable controlled by the processing marketing needs | Seasonal controlled by the catch and seasons | Undetermined |

Price settling mechanism

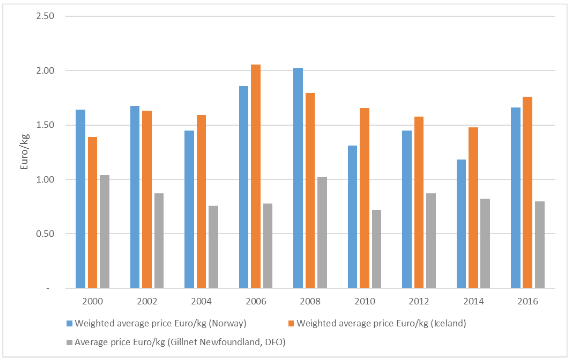

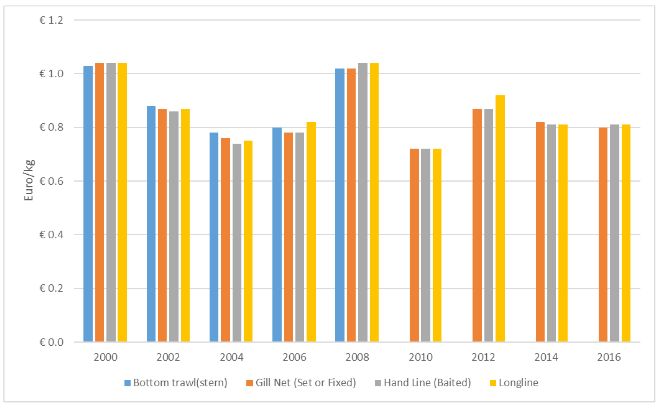

One of the factors determine the dynamic in the value chain is the first gate price that the industry is capable of paying for the raw material and the form of selling. It is also interesting to study how effective the price settling mechanism is in rewarding for attributes of the raw material, like quality and fishing gear used. In Figure 15 development of the first gate price is expressed as weighted average price.

Figure 15. First sale price as weighted average price for cod in Norway and Iceland 2000-2016.

Iceland has three ways of exchanging fish:

- Auction markets sells around 16% of the total landed cod,

- The VICs are responsible for around 70% of the landed catch and process

most of the catches in own processing facilities. The price to the VIC ́s is connected to the auction price in Iceland.

- Contracts between individual boat owners and producers is responsible

for 14% of the first sales. In Norway there are two main form of trade of fish from fisherman to producers:

- Fresh fish is traded upon direct agreements between seller and buyer, but

with minimise price settling according to Act of the Fish Sales organizations (Fiskesalgslagsloven), which gives sales organizations owned by the fishers monopoly in the first hand trade of fish. In the case of cod, two of those organization are responsible for nearly 99 % of all cod landed by Norwegian fishers (in 2016). The sales organizations are responsible for setting minimum prices for fish which is in most cases the price in the transaction.

- Frozen fish is sold on auction or by own acquisition, where the vessel

owner upon landing himself takes care the sale of fish. In general, frozen cod either goes to clipfish production or is exported unprocessed abroad, while fresh cod to a greater degree is processed where it is landed. In Newfoundland first hand price is negated before the start of the respective fishing season.

- This is done by The Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union (FFAW) and the

processing companies convene as a price settling panel to negotiate the first gate prices paid to harvesters.

- The grade or quality of the product constitutes the price received with cod

graded as either Grade A, B, C, or reject. The negotiated price is considered the minimum price and it is often augmented by the processing companies.

Price according to fishing gear

It is important to understand if the price settling mechanism is rewarding fisherman for attribute that could affect the value creation in later stages in the value chain. These attributes are for example quality, timing, size of fish, fishing gear and temperature of the fish. It is impossible to evaluate all those factors, but it is possible to evaluate the ability of the price settling mechanism to pay different price according to fishing gear.

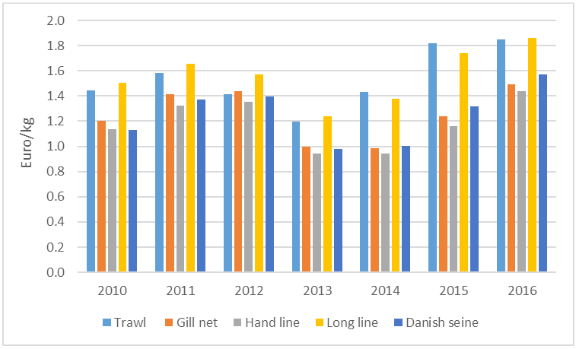

Figure 16. Norway, price according to fishing gear Euros/kg 2010 to 2016

It is clear that the price is different in Norway after according to the fishing gear.

- Longline and trawl receive the highest price but it is interesting that hand

line usually gets the lowest price which is in contrast with the general believe that hook and line fish have the best quality. The price difference is quite high or up to 0.58 euro in 2015 between the highest and the lowest. Which means that the lowest price in 33% lower than the highest.

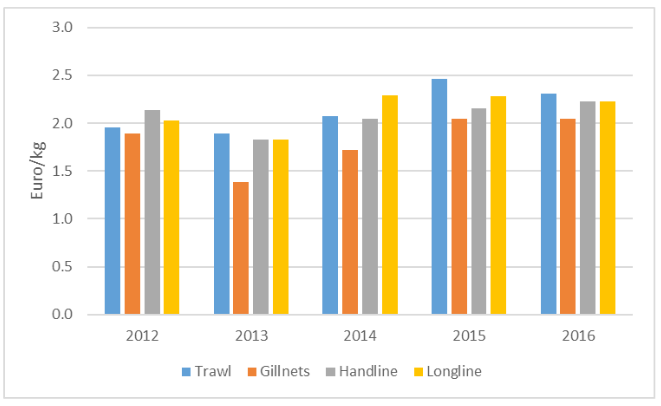

Figure 17. Iceland, price according to fishing gear Euros/kg 2012 to 2016

Price varies according to fishing gear in Iceland.

- The same trends can be detected as in Norway that the longline and trawl

receive usually the highest price. Gillnets receive the lowest price but hand line receive the highest price in 2012, although the share of the total landed cod is rather low.

- The price difference between the highest and lowest price range between

0.25 to 0.51 euros per kilo and is biggest in 2013 when the difference is 27%.

- It is interesting to see the difference in price between hand line in Norway

and Iceland that races questions about quality and the how active the price settling mechanism is in identifying and rewarding for quality.

Figure 18 Newfoundland, price according to fishing gear Euros/kg 2000 to 2016

In Newfoundland there is no difference according to fishing gear indicating there is no efficiency in the price settling mechanism to identify quality and pay incentives for that. There are recent examples were processing companies are engaged in collaborative relationships with harvesters and are paying higher premiums to those using fishing gear that produce a premium product.

Summary of main influencing factors on value chain dynamic

| Factor | Iceland | Norway | Newfoundland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Price settling | Auction markets Price settling committee but the auction price is

used as benchmark for other prices calculations in vertically integrated companies (VIC). |

Minimize price decided by sales organizations owned by the fishers for fresh

fish Frozen fish is put up to auction |

Minimize price negotiated in the beginning of the season |

| Market activities | Active | Limited | Low |

| Transparency in price settling | High Transparency in price formation – online auctions.

Equal access to auctions. Price to harvester has increased. |

Low | Low |

| Dynamic of the price settling mechanism | They play important role in returning marketing signal to the harvesting sector

making price formation transparent and market based Provided necessary quality incentives Facilitate the utilization of by-products |

The price settling mechanism has been effective in avoiding “noise” or sharp changes

on fish price to fishermen. Less part goes through auction markets of the offshore fish. |

None or limited |

| Different price according to fishing gear | Active | Active | Limited |

| Quality | Not possible to evaluate | Not possible to evaluate | Not possible to evaluate |

| Role of Auction markets regarding Specialisation | The auction markets have support specialisation in processing. Transforming heterogenetic raw

material into standardise lots for processing (spices, size,quality) |

Limited | Limited |

| Role of Auction markets regarding flow of raw material | They provide a stable flow of raw material to many small processors, creating a lower entry barrier for

entrepreneurs in fish processing. Helps maintaining competition in the processing. Foreign companies are on the market. Even out short run catch variations. Pressed for new product mix. Create channel for by-catch species and undersized fish. Creates critical mass in small species/economic of scale Supported more efficient logistic |

Seasonal flow of material | Auction markets non-existent. Seasonal flow of material |

Fishing

Fishing gear

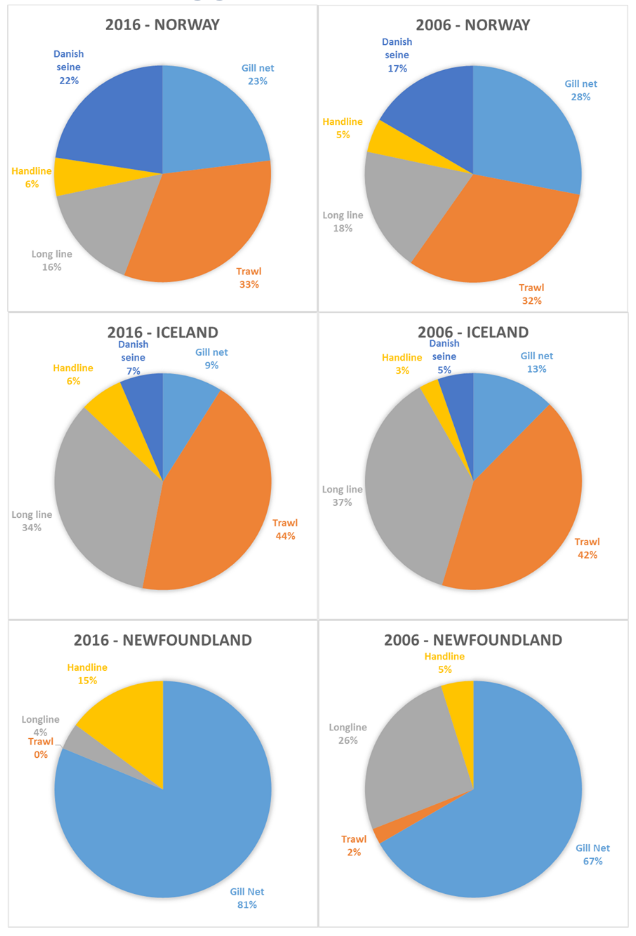

Figure 19. Newfoundland, Icelandic and Norwegian cod catch by fishing gear as share of total catch for the years 2016 and 2006.

Use of gillnets in Newfoundland had been dominated fishing gear accounting for around 80% of the total catch in 2016. In 1998 use of gillnet was around 62% and longline was around 28% but since then use of longline has been decreasing and in 2016 it counts for 3.9%. Use of hand line has been increasing or from 6.4% in 1998 to 14.9% in 2016. The reasons are:

- No active auction markets

- Very limited price difference between fishing gear

- Very limited marketing effect in the relationships between producers and

fisherman’s.

- The use of gillnets and lack of markets connection suggest that most

fisherman focus on minimising the cost of fishing and low cost strategy. Trawl is the most important fishing gear in Iceland with around 43% of the total catch in 2016. The main change in development of fishing gear is that the share of gillnets has steadily been decreasing from around 33% in 1982 to 13% in 2006 down to 8.8% in 2016. Longline has been increasing it share or from 11% in 1982 to 37% in 2006 and is around 33.5% in 2016. Use of hand line has increased mainly due to the introduction of coastal fishing in 2008. The share of hand line is around 6% and has double from 2006 when it was around 3% which is similar as in 1982. The reasons are:

- The auction market in Iceland is active

- Price varies between fishing gear is creating incentives for better quality

- The strategy is in most cases on quality and maximising the revenue

In Norway, trawl is the most important fishing gear and accounts for 33% in 2016 which is increase of 1% since 2006. The use of gillnets has been going down from 2006 when the share was 28% to 23% in 2016. The biggest increase is in use of Danish seine has been increasing from 17% in 2006 to 22% in 2016. The reasons are:

- Clear difference in price between fishing gear

- Suggesting quality incentives in the relationship between producers

and fisherman

- Seasonal fishing and use of gillnet and Danish seine suggest that the focus

in fishing is mainly on minimizing cost of fishing

Performance and profitability

Profitability in fishing in Norway and Iceland have been rather low during the past. In figure 20 all the demersal vessel from small boats to processing trawlers are expressed. This is net profit of the operation as share of revenue (EBIT = Earnings Before Interest & Tax).

Figure 20. Profitability for the demersal fishing sector, based on EBIT as share of revenue.

- The profitability in Norway and Iceland varies a lot but the profitability in

Iceland is considerable higher than in Norway. The EBIT in Norwegian demersal fisheries has been rather low or in most cases below 10% with few exceptions.

- There is difference in the fleet groups as in Norway cod trawler are

returning highest profitability in the last years and the coastal fleet or smaller vessels are less profitable. The same trend is in Iceland as small boat fleet is returning lower profitability than fresh fish trawler and bigger vessels.

Performance

Fishing per vessel have increase a lot last years both in Iceland and Norway while it has rather decreased in Newfoundland.

- Trawler in Norway is fishing 43.8% more in 2016 than 2008

- Coastal boat 15-21 m Norway are fishing 145.7% more in 2016 than 2008

- Trawler in Iceland is fishing 36,0% more in 2016 than 2008

- From 1998 the increase is 136%

- Medium vessel is fishing 24.1% more in 2016 than 2008.

- From 1998 the increase is 367 %

- The change in Newfoundland depend on the size class.

- Average vessel is fishing 3.0% less in 2016 than 2008.

- Looking further back the or from 1998 this development has been

the same except for the class size 45 to 54 feet

| Factor | Iceland | Norway | Newfoundland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fisheries management system | ITQ system pushed for consolidation increased efficiency more catches pr. boat

fewer boats catching more fish fresh fish trawlers have been the most profitable reduction on processing trawlers Costal fisheries struggling financially |

Quota system have supported increased efficiency and catch per vessel has increased.

Profitability has been increasing |

Restriction and limited catch per vessel. Catch level have been decreasing Lack of flexibility

and transferability |

| Profitability | Medium/High | Low/Medium | Undetermined |

| Productivity | Productivity has increased because of more automation, both in fishing and

processing of seafood. More catches pr. boat |

Productivity has increased because of more automation, both in fishing and

processing of seafood. More catches pr. boat |

Limitation of catch per week and lack of transferability of licences limits the productivity |

| Processing | Fish is more processed in Iceland instead of exporting HG (headed and gutted) fish for

further processing abroad. Changes from processing on sea to processing on land, where utilization is better (better filleting) |

Emphasis on minimum processing that is H/G frozen at sea

or export of Skei H/G fresh fish. Fillet production has been decreasing |

Emphasis on frozen fillet production. |

Consolidation in the sector

One way of expressing consolidation in the seafood sector in different countries is to calculate HHI or Herfindahl, Hirschman index which for the seafood sector can be calculated by summing up the squared quota shares of the firms in question. The index value is found by the sum of the squared market shares of all firms (N): and can be expressed as a normalized figure (0 ≤ HHI ≤ 1), or taking numbers between 5 and 10,000, for whether market shares are expressed in percentages or rates. For a company with 100 per cent market share the value will be 10,000 (or corresponding 1), while for a market with 10 firms and 10 per cent market share each the value will be 1,000 or 0.1.

Iceland

Concentration ratios are calculated by simply adding together the quota shares of a pre-determined number of firms. A five firm concentration ratio will thus show the combined quota share of the five largest firms, but will not consider how the quota is shared within this group of firms. The HHI values obtained in the Icelandic study indicated that the market for quota shares is competitive. This is hardly surprising, given that there are quota ceilings in place for both fleet segments. However, although relatively small, the HHI values have increased over the period under study; by two thirds for the larger vessels and more than three times for the hook-and-line boats. Some further consolidation has occurred since the fishing year 2014/2015 with individual boats or trawlers with quota or just quota being bought by VICs, however, the HHI is probably still far less than 1000, indicating low market concentration.

Norway

The Norwegian whitefish sector is a heterogeneous branch consisting of very different units in all links of the value chain – from small independent coastal vessels, fishing and delivering fresh whitefish (mainly cod), to smaller or larger seafood processors in rural areas, to large (concentrated or diversified) concerns of firms with a fleet of integrated (freezing) trawlers. Our choice of case study firms show intendedly only sparse examples of businesses found in this sector, since there is practically no “typical” firm in this industry. They are however, examples of firms that we find in this sector.

For the sellers of cod/whitefish in the first hand market in the Norwegian seafood value chain (fisheries) it is obvious that the first hand market of fish is the relevant market. However, the products sold on in this market are not necessarily homogeneous, and therefore substitutes to such a degree that they all should be weighed together.

The largest company has a 15 per cent market share in 2010, while 17 per cent in 2015. Increased concentration was seen in this market from 2010 to 2015, but still at modest level. Hence, the first hand market for frozen fish should also be deemed “un-concentrated” when following the rule of thumb, where the “cut-off” to becoming moderately concentrated, was 0.15.

Newfoundland

HHI index was not calculated for Newfoundland due to low concentration in the cod fishing in Newfoundland. The NL cod fishery is a relatively homogenous industry with the majority of landings (~95%) coming from predominately small, independently owned and operated vessels <45 feet (13.7m) in length. Comparatively, there are much fewer larger companies with fully integrated systems in operation. There are approximately 73 primary and 2 secondary processing facilities, the majority of which compete for available cod catches. The current fisheries management structure in NL, in particular the allocations of quota or weekly catch limits, caps the number of licenses an enterprise can acquire. Similarly, the fleet separation policy is also having an impact on the level of concentration, the competitiveness and consolidation by harvesters and processing companies.

Summary of main influencing factors regarding concentration

- According to HHI index calculated for Iceland and Norway there is no real

danger of too high consolidation in the value chains. The HHI index was not calculated for Newfoundland fisheries due lack of data and it was obvious that the degree of consolidation is very low.

- It is though question if calculating the HHI index is the right way of

measure the danger of too much consolidation in the fishing sector as it is mainly meant for calculating market domination rather than consolidation in the fishing sector.

- Too calculate and identify consolidation and the danger of lack of

competition in the fishing sector it would be necessary to study the different subgroups in the fishing sector, that is quota classes or size groups in those different countries.

| Factor | Iceland | Norway | Newfoundland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction on consolidation | Quota celling For vessels operating under the regular quota

system, the combined share in all fisheries may not exceed 12% in cod equivalents, The corresponding maximum for hook-and-line boats is 5%. |

Limits to quota consolidation both in offshore vessels 15% and cod trawler,12

quota factors accounting for around 13% of the share. For coastal vessels there are not quota limits. |

Limits of stacking of licences, maximise three licences |

| HHI index | Low consolidation | Low consolidation | Not calculated but very low consolidation |

Overall economic performance and competitiveness of the fisheries value chain

Value chain dynamics depends heavily on the governmental form of the vale chain and the relationship within the value chain and the governance form. Geraffi claims that in many chains are characteristic of dominate party/parties who determine overall character of the chain. In the same way the lead firm(s) becomes then responsible for upgrading activities within individual links and coordinating interaction between links in the value chain. Hence, the role of governance in the value chain is important and Geraffi[ CITATION Ger94 \l 1039 ] makes distinction between two types of governance in value chain, first where buyers is undertaken coordination in the value chain (buyer drive commodity chains) and those which producers play key role of coordination (producer-driven commodity chains). In fisheries that builds on natural resource, it is interesting to analyse the different forces in the value chains and how activities are impacting the results of the value chain.

Iceland

Governmental form of the value chain

Links between fishery and producer’s

- One of the most important changes of the domestic value chain dynamic

was the establishment of the auction markets.

- Before that the most common form of the governmental of the domestic

part of the value chain was either hierarchy through VIC or relational through landing agreements between individual boat owners and producers.

- In some cases, there are market relationships where individual boat

owner based their relationship with the producers on just the highest available price.

- By the establishment of the auction markets more and more of the

individual boat owners moved their business to the auction markets increasing the emphasis of the market form.

- Then after the implementing the ITQ system more of the TAC moved to the

VIC as can be seen that only around 15% of cod is sold through the auction markets and around 70% thought he VICs.

- There are mainly two form of governmental structure in the

domestic part of the value chain of cod that is markets based on supply and demand of the auction markets and hierarchy relationship through vertical integrated companies. Other form as relational can still be identified but in limited cases. Producers export links

- During the period before 1994 when the limited export licences were still

active the governmental structure of the value chain of cod from fishing to markets was Captive form as the sale organisation in key position in the value chain where producers had duty of handing inn all their product for selling thought the SMOs.

- The export part of the value chain has as changed a lot for the last 30

years. The bigger VIC have in many cases established their own marketing division or even their own marketing companies abroad depending on hierarchy form of governance.

- In most cases Icelandic companies are selling to middleman abroad as

distributers or wholesalers, although some are selling directly to retail chain as in the fresh fish markets. In most cases companies have contract with buyers that that could be regarded as relational from of governance. Dependency

- The dependency in the value chain varies a lot depending degree of long

term contracts in their business instead of ad hoc sale. In interview with mangers in the Icelandic fish industry it is clear that more and more of the TAC is sold before it is caught. This indicates long term relationship and relational governance form in the export part of the value chain term relationship Power structure/balance

- It is in the nature of quota system that the quota holder has the power in

the value chain. Hence it is in the hands of the quota holders when where and how the fish is caught and then for others to try to make the most out of the raw material that is brought onshore. Due to high degree of VICs (70%) in the value chain in Iceland, the negative effects of this power is not real. Auction markets are as well important for power balance as they send markets signal to the independent fisherman about quality, fishing gear and even timing. The power balance between links in the value chain are in good balance in the Icelandic value chain

Drive force in the value chain

The drive force in the value chain have changed a lot the last 30 years from having:

- harvesting/production driven value chain to becoming more and more

marketing driven value chain. The main reasons for this changes can be trace to:

- Introduction of auction markets in 1987

- Introduction of the ITQ system in 1991

- Abolishment of strict and limited export licences opening up for

more marketing connection of producers.

- The drive force for changes in the dynamic of the value chain of Icelandic

cod areo FMS (ITQ) system that allows companies to maximize their returns and plan according to market condition

- Direct marketing connection and understanding of market situation

- Coordination in the value chain mainly done through the hierarchy

in the VIC

- Auction markets

production

- Power balance. In quota system it is clear that the formal power lies

with the quota holder or the individual that has the TAC. Due to the fact that around 70% of the TAC is hold by the VIC companies so it is clear that they are the most powerful players in the value chain. Due to limits to the consolidation that is 12% in the demersal spices there are limits to how individual company can dominate the industry.

- Vertical integration support power balance in the value chain

Support coordination and specialisation in Norway

Governmental Form

- In modern times (after WWII), up until the new seafood export legislation

in the 1990’ies, all branches in the cod sector was subject to the trade conditions dictated by the sectoral export commissions. These commissions was leading actors in the centralised export, where they lead negotiations and entered into common agreements for most all important seafood products. They were, like in Iceland at that time, a captive lead firm that explicitly coordinated the export, and by that had great influence on the business environment.

- After the new Export Act in 1992, these export commissions were

dissolved, and new liberal rules granted practically anyone paying an export fee could to start export of seafood. With this many processors above a certain side (or even just processors that have found it opportunistic) have started their own export. There are of course cooperation between exporters, processors and both, where some quantities/products/species are sold by standalone exporters, while some have caretaker in-house, but in general the structure and governance form in the marketing sector is atomistic. Some large exporters exists within some products, and also some major processing firms dominate the export of other products, but in general a market to modular form of this trade is the usual. This is our impression of the chain as a whole, and we cannot see a big development towards one governmental form or the other throughout the latest 10 to 20 years.

- The power between purchasers and suppliers is balanced in the way that

terms of trade is governed by the price, even though relations play a role together with trust and esteem/reputation.Power balance/structure

- The consolidation in the fleet might have had an effect on the power

balance, and some would maintain that the fishing industry have increased their power on expense of the processing industry.

- Others again, would maintain that the processing industry, by ways of

consolidation in this link of the chain, have ascertained increased power over the fishing/selling side of the transaction.

- However, the heterogeneity of the fishing sector makes it impossible to

conclude unanimously on this matter. In some areas for some vessel groups consolidation might have increased the fishing side’s power towards the processing sector, whereas in other areas the opposite might be the case. The power balance might also depend on the aggregated demand and supply situation, and as such depend on the cod quota available for the industry.

Drive force in the value chain

- The development of the Norwegian seafood industry has over time

followed a trend of liberalization, where the emphasis has changed from protection and subsidies (pre-1990’ies) to international competitiveness and environmental and economic sustainability. It is not easy to set a clear division in time where this policy change occurs, but over time the emphasis has gone in that direction.

- From early 1970’ies as a process where resources and resource allocations

becomes the main theme in the fisheries policy, while negotiations on subsidies and its distributions becomes secondary.

- In the mid-1990’ies, Norway has left a period with free conduct on the

ocean and regulated market behaviour, to one with regulated conduct on sea and free competition in the market. Earlier (pre-1990’ies), the seafood export was organised in trade unions, dependent on product (dried fish, salt fish, fresh fish, frozen fish and clipfish) whereas a deregulation of the seafood export act in early 1990’ies open up for anyone – satisfying a set of objective criteria, to export seafood.

- In the first hand market, the abolishment of subsidies involved that the

price wedge between supply and demand was removed, enabling price movements in the market to be directly transferred to fishers.

- Sales organisations’ right to set minimum prices still meant a

share of market power on behalf of fishers, but also here the development towards a dynamic minimum price – dependent on objective and observable factors on the market place – have reduced the shielding of fishermen from market signals.

- The reduction of both fishing vessels and purchasers along the coast, has

consolidated and professionalised the industry on both sides of the transaction in the first hand market.9.3 Newfoundland

Governmental Form

- In Newfoundland it is possible to separate the fishing industry into two

sectors. First is the offshore sector that is vertical integrated in fishing, processing and marketing and then inshore fleet, which is based up on individual boat owners where vertical integration is banned.

- Today TAC in cod is only allocated to the inshore sector (TAC will need to

exceed 115.000 thousand tons before it is reallocated to the offshore sector).

- The links between boat owner and producers is based on negotiated price

between FFAW (The Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union) and associations of producers. There are no auction markets and more or less the negotiated price is used in the transaction.

- The relationship is in some way captive due to lack of active markets in

the relationship but in some cases it could be regarded relational where boat owner and producers have some contract about landing of cod and other spices.

- Stakeholders seems to play more active role in governing the value chain

and its structure than in other countries as allocation of quota and limits on transferability seems to depend on the stakeholders as FFAW. Power balance/structure

- Due to the structure of the fisheries management system that is individual

vessel do not have TAC (have to follow the weekly limits of catch) and very limited possibility of transferring fishing licenses (stacking up) the power in the value chain lies in the hands of the stakeholders that decides on the system.

- The stakeholders are the policymakers that is the politicians and the

parliament that decide on the system. Secondly it is the FFAW that plays big role in influencing the system and deciding of how it is conducted.

- FFAW and negotiated agreements are having significant influence on the

free markets; the agreements preventing markets relationship and market influence in the value chain.

Drive force in the value chain

- Due to low quota in Newfoundland and more important species as lobster

and crab, cod have been looked up as filling and not major species in fishing. With foreseeable increase in quota this can become problematic.

- The fishing of cod in gillnet during August points out that the drive force is

minimising the cost of fishing rather than anything else.

- Longer season and strict rules about transferring quota (stacking up)

points out that the fishing is looked at as a social aspect rather than building up economic sustainable business. The influence of stakeholders seams to affect the economical sustainability of the industry.

Summary of main influencing factors regarding concentration

- The structure and the governance of the value chain, Vertical integration is

creating more value per kg of raw material and returning higher profit

- The profitability is higher than in other system

- The market responsive is better

- The flow and stability is better

- In value chain where vertical integration is banned or limited the strategy

of fishing is more or less to minimise the cost of fishing.

- Seasonal fishing

- Use of gillnets is common

- The auction markets in Iceland has created new source of dynamic in the

value chain that is specialisation in production

Companies selling of species and sizes that do not fit their production mix

- Iceland has freedom on decide on its structure that is vertical integration

or not

- Norway has limits on vertical integration in the coastal fishing

- Newfoundland ban vertical integration in inshore fleet.

- Source of competitiveness of the value chains

| Factor | Iceland | Norway | Newfoundland |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure of the industry | Vertical integrations Hierarchy Market through auction markets | Limits to vertical integrations Individual boat owner and producers | Ban on vertical integration’s in the inshore fleet. Offshore fleet has no cod quota |

| Vertical integrations | High | Low | Low/none in inshore fleet |

| Flow of raw material | Stable controlled by the processing marketing needs | Seasonal controlled by the catch and seasons | Seasonal controlled by catch limits and fisherman’s effort |

| Governance | Mainly through hierarchy of VICs or use of auction markets

Market relationship, based on auction markets |

The role of minimum price affect the dynamic in the value chain | Significant stakeholder involvement such as FFAW |

| Coordination | High in the VICs and based on buyers need in some sense.

In the auction markets coordination is limited |

Low in coastal fleet In the offshore fleet it could be high due to

vertical integration |

Very low in inshore fleet; some in the offshore sector and cooperatives |

| Dependency | High in the hierarchy low in the market based | High in the hierarchy low in the market based | Low but minimum processing requirements can create dependency

between fishing and production |

| Power structure/balance | Twofold Hierarchy with high dependency by sectors and power balance Markets based on

power of quota holders. Low dependency |

Twofold Hierarchy with high dependency by sectors and power balance Markets based on

power of quota holders. Lowdependency |

Unbalanced power lies in the hands of stakeholders mainly FFAW |

| Drive force | Buyer driven value chain based on coordination of fishing and production through

VICs and auction markets |

Harvesting (product) driven value chain. Based on minimising cost strategy of fisherman’s | Harvesting (product) driven value chain, Stakeholders driven (FFAW) Based on minimising cost

strategy of fisherman |

| Lead firm | VICs | Owner of the off shore fleet. | None/FFAW on behalf of small boat owners |

| Specialisation | Rather high ITQ in in fishing Auction markets for processing, spices, sizes etc. | Rather low or limited | Very low seasonal industry |

Strategic Positioning Briefing

Iceland

In general the main strength of the Icelandic system is the distribution of catches around the whole year, strengthen by the start of the quota year on 1. September each year. The industry is putting more emphasis on production of fresh fish instead of frozen or salted product with huge investment in new fresh fish trawlers. The processing companies have also been investing in new equipment, especially regarding water cutting and super-chilling. With super- chilling and good control of temperature in containers, more emphasis has been put in transportation on sea rather than by plane. This is related to cost but also to carbon footprint. There is also more emphasis on markets in N-Amerika and the industry in closely monitoring developments in Asia. VICs are extremely strong as they control more than 2/3 of the cod quota and therefore limited amount is going through the auction markets.

| Description | Share cod quota | Access barriers | Opportunities and upgrade possibilities | Threats | Value chain relationship | Dynamic in the value chain | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open vessel group | 2000 vessels <11m, max. vessel quota 15-24t (length dep.) guaranteed 11-18t | 6.8 % | Low | Pressure due to high uptake and stop. Opportunities in other fisheries than cod, and quota purchase. | Lower cod quotas. Regional differences in availability and landing opportunities.

New safety regulations will increase capital demands. |

Direct agreement with buyers, little influence on price. | Open fishery with entry under profitable circumstances |

| Coastal vessels under 11m | 1200 vessels, with vessel quota of 25- 50t | 14.1 % | Relatively low. Higher quota prices up to 350kEUR | Differentiation through quality, opportunities in other fisheries (king crab, haddock) and co-fishing | Uncertainty regarding future fisheries management system, (structuring and vessel length

limits). Structural development in landing sites. |

Direct agreements with buyers. Often close ties with local purchaser. | Maximize first hand value, often with low cost focus (seasonality). |

| Coastal vessels, 11m and above | 560 vessels, with

structuring, vessel quotas of 50-166t |

37.1 % | High - capital intensive, due quota price | Better handling. Sale contracts with producers. Many generalists with rights in pelagic sector also. | Uncertainty regarding fisheries management system, potential introduction of resource rent tax, affecting profitability. | Direct agreements, high mobility and in greater (volume) demand. | Maximize first hand value, low cost focus (seasonality). On board freezing incr. |

| Off shore vessels (auto-line and trawl) | 26 conventional vessels (autoline), vessel quota >274t 36 cod trawlers, vessel quota >1,096t | 8 %

30.8 % |

Very high | On board processing potential exploited by few. High quality on hook catch, with price

premium. Tendencies towards own sale. Structuring potential exploited. |

Currency and quota fluctuations. Uncertainty regarding future management options and resource rent tax. | Auction sale of frozen fish, tendency towards contracts and own takeover of catch | Maximize value from catch. Full capacity utilisation with later years’ quotas. |

| White fish processing firms | Companies with processing facilities, some with vessel ownership, some

with export licence. Great heterogeneity. |

0 | Low to medium, dependent of capital intensity of production. | Choice of product mix. Increasingly capital intensive processing have led to big fresh fish export under high

quotas and seasonality. Falling quotas can counter this dev. |

Favourable but unstable currency fluctuations. Seasonality in supply. Much fish surpass traditional supply

channels, to an increasing degree. Thawing have reduced comp. power of fresh. High Norw. salary level. |

Tough competition up- and downstream the value chain, but close ties and trust | Small margins and low profitability on average. Liquidity challenges in production of conventional prod. |

| Export and marketing companies | Many exporters of varying size, markets and product portfolio.

In-house, stand alone and preferred traders. |

0 | Low | Small degree of own brands in international seafood trade, especially with raw material and semi-finished products.

Supported by the generic marketing of seafood from the Norw. Seafood council. |

Currency fluctuation. Lack of branding. Seasonal landings complicates continuous supply of fresh fish. | Demanding retail chains and spot markets. Price signals most important but also relational customer ties. | Monitor markets needs and preferences and share market signals to producers. Multiple and regional