Difference between revisions of "Deliverable 3.4"

Jacandrade (talk | contribs) (Created page with " = Deliverable D3.4 - Report on evaluation of industry dynamics opportunities and threats to industry = ---- ---- == Executive Summary == ---- In this report, evaluation...") |

(No difference)

|

Revision as of 01:47, 5 July 2018

Contents

- 1 Deliverable D3.4 - Report on evaluation of industry dynamics opportunities and threats to industry

- 1.1 Executive Summary

- 1.2 Atlantic cod

- 1.2.1 Summary

- 1.2.2 Global Market review

- 1.2.3 Fisheries Management System in Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland

- 1.3 Atlantic Herring

- 1.4 Salmon

- 1.5 Rainbow trout

- 1.6 Sea bass & bream

- 1.7 Pangasius

- 1.8 Bibliography

Deliverable D3.4 - Report on evaluation of industry dynamics opportunities and threats to industry

Executive Summary

In this report, evaluation of industry dynamics opportunities and threats to industry, we are focusing on value chain dynamic for certain industries and species. The framework used is a bit different for caught species (cod and herring) and farmed species (salmonoids, sea bream & bass and pangasius). The industry dynamics is more value chain focused for the caught species, while individual companies are also the focus for the farmed species. The main results for the caught species reviled very interesting structural difference and functionality of the value chains for cod between Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland. Previous studies have argued that the superior harvesting and marketing strategies of the Icelandic industry may be rooted in factor conditions that are difficult to duplicate and a rigid institutional framework in Norway and partly the social resource structure of the Newfoundland industry, where market conditions have very limited consideration in terms of the structure or management of the industry.

The vertically integrated companies in Iceland where the processor owns its own fishing vessels. Unlike the push supply chain system followed by the Norwegian and partly the Newfoundland companies where they must process the fish that they receive, the Icelandic processors places orders to its fishing vessels based on the customer orders and quota status, thus following a pull supply chain system. The Icelandic processors are able to sends orders to the vessels for how much fish of each main spices is wanted, where to catch and to land so they have the desired size and quality of raw material needed for fulfilling customer orders. This structural difference is also affecting the product mix that the countries are going for.

It is also very interesting to see the difference in structure and functionality of the value chains between Norway, Iceland, Denmark and Newfoundland for herring. The structure of the industries is different as seen in the degree of vertical integration and the limits that government’s put on the industries. It is though surprising how homogeneous the industry is between those nations. The nature of pelagic species that is, seasonality and high catch volumes in short periods, makes the product global commodity for further processing from one season to the next. The main markets are Business to Business (B2B)

The first noticeable difference observed, apart from the structure, is the price settling mechanism. On one hand it is the Norwegian system that builds on minimum price and auction market which is the same that is used to determine the Danish price. In Iceland the price is decided by the Official Bureau of Ex- Vessel Fish Prices. he Norwegian price is in many cases double that of the price in Iceland. The price obviously affects the profitability of the industry as the Norwegian fishing is benefiting from high price but the processing sector is suffering from low profitability. On the other hand, the processing sector in Iceland is doing well as well as the profitability of the fishing is healthy. It can be claimed that the overall profitability is higher in Iceland due to the freedom of strategically positioning yourself in the value chain and being vertical integrated or not, without external limitation as those that can been seen in Norway, Denmark and Newfoundland

Aquaculture is the primary source of salmonid supply globally. The different salmonid species available on the market are substitutable to a considerable extent due to their pink flesh colour and similar properties. However, different dynamics in the broader competitive environment, and in the particular circumstances of national sectors, in which the businesses comprising these industries are embedded, have determined different developmental trajectories for the very same industries. These dynamics include the changing nature of consumer demand characteristics, production technology, national regulatory regimes, international trade, industry structure, availability of natural resources. Discussed in this chapter are the cases of farmed Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout in major producer countries and the role key external influences have played in shaping different developmental outcomes. The interaction of selected salmonid producer firms with their distinct competitive environments is illustrated through firm-level case studies of strategic positioning.

The output of most salmonid aquaculture, and Atlantic salmon in particular, is highly commoditised i.e. there is little differentiation between farms and competition is based purely on price. These products, mostly head-on gutted fresh fish, serve as raw material for further processing. In that situation, large enterprises which can reduce costs of production economies of scale and offer the lowest price, would have competitive advantage.

Seabass and seabream are the most important species for the aquaculture of fish in Spain, being one of the most important markets in Europe. The production and the market is highly concentrated and economies of scale may improve the competitiveness of the sector. The integration of production and the stable international trade allows to increase the share of the price value. The pangasius industry in Viet Nam has grown quickly over the last two decades to become one of the main food exports from the country and a major contributor to the Vietnamese economy. Pangasius products, mainly frozen fillets, are currently exported all over the world, with the largest markets being the EU, the USA, and more recently China. The success in market penetration of pangasius products can be attributed to their mild taste, lack of bones, and most importantly their low price compared to other, more traditional whitefish products, for which it acts as a low-cost substitute.

The production node in the pangasius’s value chain was initially highly fragmented, composed of many small-scale family owned enterprises and middle-scale processor-exporters. However, the industry is undergoing a rapid a rapid consolidation and increasingly being served by large-scale vertically integrated enterprises, encompassing all stages of the value chain. The reasons for that can be found in the improvement in seed production methods, control of fish health and disease problems, feed and nutrition and market requirements.

Atlantic cod

Summary

It is very interesting to see the difference in structure and functionality of the value chains between Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland. Previous studies have argued that the superior harvesting and marketing strategies of the Icelandic industry may be rooted in factor conditions that are difficult to duplicate and a rigid institutional framework in Norway and partly the social resource structure of the Newfoundland industry, where market conditions have very limited consideration in terms of the structure or management of the industry.

The vertically integrated companies in Iceland where the processor owns its own fishing vessels. Unlike the push supply chain system followed by the Norwegian and partly the Newfoundland companies where they must process the fish that they receive, the Icelandic processors places orders to its fishing vessels based on the customer orders and quota status, thus following a pull supply chain system. The Icelandic processors are able to sends orders to the vessels for how much fish of each main spices is wanted, where to catch and to land so they have the desired size and quality of raw material needed for fulfilling customer orders.

This structural difference is also affecting the product mix that the countries are going for. Iceland is therefore placing more and more emphasis on fresh fillets and pieces, while the other countries are going for more traditional products, like salted, dried and frozen products. Due to the vertical integration in Iceland, the production plans are developed based on customer orders and then a plan is made for fishing, while in Norway and Newfoundland, the production plans is usually developed after receiving the fish at the processing plant as the information about volumes of specifies caught and quality is not available beforehand.

Global Market review

According to a book by Mark Kurlansky; ”Cod - A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World”. Cod was the reason Europeans set sail across the Atlantic, and it is the only reason they could. What did the Vikings eat in icy Greenland and on the five expeditions to America recorded in the Icelandic sagas? Cod, dried in the frosty air. What was the staple of the medieval diet? Cod again, sold salted by the Basques. As it turns out, cod has sparked wars, shaped international political discourse, impacted diverse cultures, markets, and the environment.

Cod importance has dwindled, but it is still of major importance to Iceland and Norway and growing importance in Newfoundland and therefore it is important to look at industry and market dynamics, opportunities and threats in the value chain of cod for these countries.

Main producers

Atlantic cod is only one of many species entering the global supply chain for whitefish, which can be viewed as substitutes. Amongst them, we find Alaska pollock, hake, saithe, Pacific cod, haddock, hoki and Atlantic redfish. Altogether, the global supply of these species in 2015 was about 6,937 million tonnes, according to FAO. The largest species by far is Alaska Pollock, for which the catch in 2015 added up to 3.3 billion tonnes – 48 per cent of the total whitefish supply – for which US and Russia are the largest actors.

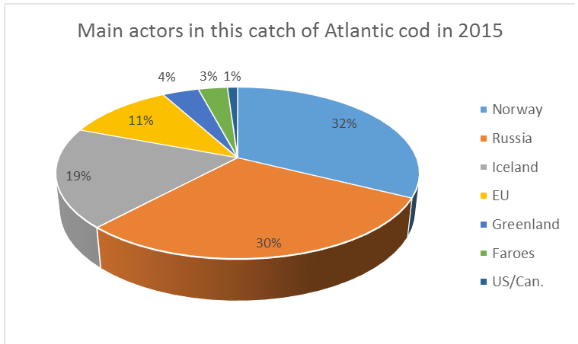

Atlantic cod was the second largest species in the global whitefish supply in 2015, responsible for 1,304 million tonnes, or 19 per cent of the total. The main actors in this catch of Atlantic cod in 2015 was Norway, Russia, Iceland and the EU with 11% of the catches as can been seen in figure 1. The main actors among the EU countries are Denmark, UK, Germany and Poland. The main suppliers since the turn of the century are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Main actors catching Atlantic cod in 2015 according to FAO

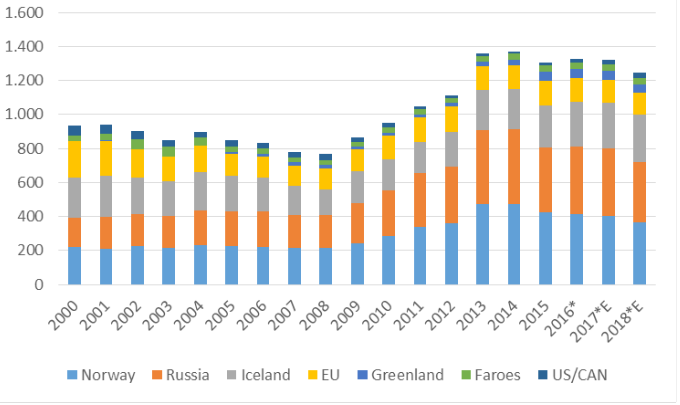

Figure 2. Supply of Atlantic cod from the North Atlantic waters, by country, 1000 tonnes, 2000–2018. Source: FAO and (*) Groundfish Forum

FIgure 2 shows a relatively stable distribution of cod catches until the increase in the quotas for Northeast Atlantic cod about 2009, where Norway and Russia increased their share. Moreover, it shows that the catch of US/CAN fell until the end of this period, when it rose again, and that Greenland catches have increased over the period. As can been seen in Figure 2, The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) has recommended a 20 percent cut in the Barents Sea cod quota for 2018. However, the Joint Russian Federation- Norwegian Fisheries Commission in October 2017 agreed on the 2018 quotas, which include a 13 percent cut in the Barents Sea cod quota to 775.000 tonnes (FAO).

Main markets

The EU is by far the largest market for cod products in the world. Cod is processed in different format to fulfil the needs and customs of different markets. There is a big consumption of fresh and frozen product in EU, especially in UK and France. The tradition of drying fish to preserve it dates back to Viking times, but the process of salting fish began in the 15th century, when the Iberian fishermen were sailing to and from Newfoundland. Cod that had been preserved in salt would last the length of the journey. Clipfish/saltfish or bacalao is also popular in Catholic countries, thanks to a tradition that dates back to the middle ages when the pope ordered Catholics to eat fish instead of meat during Lent. Therefore have Iceland and Norway exported bacalao for centuries to Catholics around the world, especially to Spain and Portugal. There are also number of other traditional markets, like Nigeria for dried fish parts and heads. USA was also a big market for cod products, and it has been growing again in recent years, especially for fresh cod.

Cod producers from Norway have been taking putting effort in emerging market like China, where there is great potential but no custom of consuming cod products.

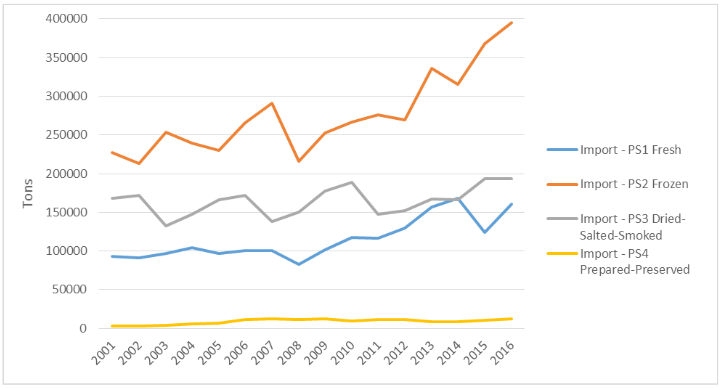

Figure 3. Trade of cod in the EU, Import of cod products in the EU, both extra and intra EU trade. Raw data from EUMOFA.

The total import in the EU was 761 thousand tons in 2016 and the imports in total have been on the rise in recent years. That don’t mean that this came all from outside of EU. Part of the imports (42.1%) came from Intra EU trade while the larger part (57.9%) came into the EU from countries outside the EU, like Norway and Iceland. Largest part of the EU export figures of 421 thousand tons are Intra EU trade or 94.1%, therefore there are only around 25 thousand tons of cod exported out of the EU to non EU countries.

Frozen cod is by far the most common preservation form of traded cod in the EU as can been seen in Error: Reference source not found. The import of dried, salted and smoked cod products have been relatively stable in recent years but the main growth has been in the import of frozen and fresh cod products. The imports of fresh cod has been on the rice since 2008, but 2015 the volume went down but gained momentum again in 2016. The imports of prepared or preserved products is low but relatively stable between years.

Fisheries Management System in Norway, Iceland and Newfoundland

General

Norway

“The main objective for the industrial and fisheries policy is the highest possible value creation in Norwegian economy, within sustainable limits. The Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries work is to obtain this main objective builds on the following sub- objectives: efficient use of society’s resources, increased innovation and adaptation ability, and companies who succeed in international market. The sub-objectives and prioritised areas to achieve these are just as important for the seafood industry as other activities in Norway. A purposeful superior effort to stimulate to increased innovation and adaptation ability in Norwegian economy is of great importance also for the seafood industry.”

Iceland

Iceland seafood sector is modern and competitive, based on sustainable harvest and protection of the marine ecosystem. Marine products have historically been the country’s leading export items and the seafood industry remains the backbone of the economy. The fisheries management in Iceland is primarily based on extensive research on the fish stocks and the marine ecosystem and biodiversity, and decisions on allowable catches are made on the basis of scientific advice from the Icelandic Marine Research Institute and catches are monitored and enforced by the Directorate of Fisheries.

Newfoundland

Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) is responsible for management of the Canadian fisheries stocks in accordance with the roles and responsibilities outlined in Canada’s Fisheries Act. The major objectives and priorities of the DFO’s fisheries management policies include ensuring environmental sustainability and conversation of the resource, ensuring access based on adjacency or proximity to the resources, consideration of the relative dependence of coastal communities and the dependence of various fleet sectors, as well as factors such as economic efficiency and fleet mobility. Inclusion of stakeholders in the decision-making process is regarded as a key priority for fisheries management in Canada (Fisheries Management Decisions, 2017; Sustainable Fisheries Framework, 2017).

Quota system: Individually Transferable Access

Norway

- Rule of thumb: Off-shore vessels governed by licenses, and coastal vessels by annual

participation rights (off-shore conventional vessels excepted).

- In order to get a fishing quota you have to buy a vessel (a pre- requisite is loosened up in later

years, where one nowadays can get hold of structured quotas, without factual vessel transactions). Transferability has increased, buts still with great imperfections compared with an ITQ-regime.

- Quota distribution to vessel groups (coastal vs. off-shore, and different size classes within

the coastal vessel group) based on allocation formulas agreed within the Norwegian Fishermen Association, upon historical rights. Still with some autonomy for the authorities to allocate certain shares of quotas to special schemes (youth, recruitment, R&D, etc.) before allocation to vessels.

- Regional distribution safeguarded by fleet composition, and limited transferability between regions

for some licenses/participation rights.

- Quota year is the same as the almanac year.

Iceland

The ownership of quotas involves the right to catch the fish but does not entail ownership of the fish stock. Thus, it is claimed that the quota does not mean the ownership of the fish but rather the right to catch the fish. Since 2001 small boats has been allocated TAC (Total allowable catches) and all effort based system abolished until 2009 when coastal fisheries was introduced. As can be seen in figure the share of small boats of the TAC was 14.2% in 1992 and is 22.3% in 2016. It peaked in 2001 when it was 24.1% of the TAC in cod. Part of this increase can be explained with changes in classification of small boats as in 2013 when small boat definition went from 15 gross registered tonnes (GRT) to 30 GRT.

- The emphasis of the fisheries management system since 2001 has been to simplify the system and bring all into the quota

system of ITQ and TAC system. Against this, open access fishing was introduced in 2009 when new system was introduced for small boat called costal fishing (isl. strandveiði).

- By the 1990 Act the fishing year was set from 1. September to 31. August in the following year but previously

it had been based on the calendar year. This was an effort to channel fishing of the groundfish stocks away from the summer months, when quality suffers more quickly and many regular factory workers are on vacation.

Newfoundland

Generally, DFO allocates quotas for each stock/species (or group of species) in accordance with a specific fishing season and within a specified fisheries management division. The key regions or fisheries management divisions for cod quota or allocation in NL are:

- 3K (including 2J3KL)

- 3Ps

- 4R (including 4R3Pn)

Information included in a fisheries decision may include:

- opening and closing dates for the season,

- total allowable catches (TAC),

- and management plans (Fisheries Management Plans, 2017) with certain fisheries managed through multi-year Integrated Fisheries

Management Plans (Integrated Fisheries Management Plans, 2017). In Newfoundland, Atlantic cod are managed through a series of strategies. Pending the NAFO region, the cod fishery can be a set quota, a weekly allowance or allocation, or may be an experimental fishery. Based on principles of adjacency and the numbers of vessels /harvesters participating in the fishery, the coastal fleet (<65 feet) has a strong position within the NL fisheries sector.

Entry barriers into the system:

Norway

The activity demand in the Participation Act states that in order to own a fishing vessel one have to be an active fisher.

- Many exceptions have been granted. Firstly, on the same footing as active fishers are administrative fishing vessel

owners – caretaking the daily operation of vessels from land. Also, as the filleting industry in the north of Norway was built up and prioritised as whole year employers, many filleting firms were granted cod trawl licenses, which today are held by two big processing concerns (Lerøy and Nergård)

- To become a registered fisher, you have to live in Norway and work on a registered Norwegian fishing vessel

- To get a vessel registered a as a fishing vessels, demands have to be met regarding size class and operating areas.

Like in other western society fisheries, the closure of the commons have increased the capital intensity, and labour is to a large degree substituted by capital intensive production equipment. Foreigners can buy vessels below 15 meters in Norway and control no more than 40 per cent for boats above 15 metres. Processing industry - no nationality limitations exists

Iceland

All professional fishing in Iceland has to have licences for fishing.

- Capital intensive due to high price of quota

- Entry for foreign investments very limited (or closed).

- Economics of size Costal fisheries

- In 2016 total 9790 thousand tones are allocated for coastal fishing one open access base from May to August.

- Open access

- Low profitability (returning loss for all years of operation)

- Coastal fishing is limited to small boats with maximum two handlines per person and

maximum two person on the boat. The maximum 650 kg catch per day and fishing is limited to four days a week.

- There are also limits of TAC for each area for the small

boats.

Newfoundland

No new licences being issued by DFO

- Entry into fishery is based on acquisition of existing licences

- Requires a professional fish harvester certification

- Significant investment in terms of education and training and at-sea experience

- Cost of entry into the fishery is prohibitive due to the high cost of capital investment (vessels,

gear, etc.) and the cost of licences

- Uncertainty over future allocation/quotas and if there will be return on investment

Exit barriers from the industry

Norway

- Exit barriers are fewer Vessel owners are unable to recover the full vessel value as they exit the industry.

- However, the increase in quota prices over the years should cover for such discrepancies.

- Limited transferability between regions in some vessel groups.

Iceland

- Low exit barriers quota easily sold and market open

- No tax limitation for selling the fishing rights and ITQ.

- Unlimited transferability between regions

Newfoundland

- Low exit barriers licenses are easily sold; open market for licence

- No regulations governing the sales

- Exit not linked to potential resource re-allocation for new entrants; i.e. portion of

share or allocation is not reinvested back into the fishery

- No financial reinvestment (e.g.no tax or fee) required to be paid by harvester upon

sale of licence and exit from the system

Quota ownership and quota prices

Norway

There is in Norway a consolidation limit for cod for both conventional off-shore vessels (auto-liners) and cod trawlers, but not for coastal vessels.

- Firms owning conventional off-shore vessels cannot, directly or indirectly, own vessels that

control more than 15 per cent of the group quota for any of the species included.

- For cod trawler, firms cannot control more vessels exceeding more than the number that

controls 12 quota factors. With today’s quota ceiling (maximum four quota factors per vessel), it means 3 full structured vessels and about 13 per cent of the group quota for cod trawlers.

- However, there are specific rules for ship owners that also own

processing facilities, which is the reason that the two before mentioned cod trawler ship owners have more vessels than the limit of the Act. Quotas can be transferred among vessels in a vessel owning company, but only upon authorities’ approval. Also, other eases of transferability exist (renting quotas, ship wrecking, replacement permit – in awaiting of new vessel, and others) A quota flexibility between years is also possible, but within the cod fishery, this is only possible on group level – not for individual vessels. An overfishing of the vessel groups’ cod quota one year will be claimed against next year’s quota, and vice versa if the full quota is not taken. For the vessel groups with a limited number of vessels, this individual vessel quota flexibility between years will be effectuated over the turn of the year from 2017 to 2018. Coastal vessels will have to wait longer until this can be effectuated, since so many extraordinary schemes exists for these vessels Quotas within Norwegian fisheries are transferable, but there exists no central brokerage system where quota prices are noted.

Iceland

Limitation on consolidation of quota ownership – max 12% ownership of TAC for each species.

- Quota is bound to fishing vessel but companies with number of vessels can transfer quota between vessels.

- 15% of TAC can be transferred between years by companies

- 5% can be overfished in the fishing year and will then be withdraw from the companies next year TAC

TAC cannot be transferred between systems, example from the hook system to the general TAC system

- There is regional restriction to fishing in the coastal fisheries

- The fishing ground is split into 4 areas

Newfoundland

Transferability allocation of quota/weekly

- Limit on combining (maximum set at 2:1 or 3:1) shares or allocation for inshore fleet

- Transfer of shares/allocation between vessels is permanent (inshore fleet);

- Larger offshore vessels can transfer quota between vessels annually- it is not permanent

- Opportunity to buddy-up is limited or restricted based on region and season

Possibilities to upgrade in the system

Norway

Upgrading is possible, but is capital intensive. Opposite to the fishing industry, no license is needed to erect processing capacity. Upstream vertical integration (towards the fishing fleet) is prohibited, while downstream (from fleet to processing) allowed. Less cod in onboard processed in the off-shore over time, but more is sold as frozen HG.

Iceland

Limitation to move between systems

- hook system is looked in there but can be transferred inside that system

- Small boats can enter the costal fisheries even if they are operating in other systems.

- only requirement’s is during that time they only operate in costal fisheries.

Newfoundland

- Limited opportunity for vertical integration based on PIICAF and allocation of first 115,000

tonnes to inshore sector

- Upgrading is based on number of licences purchased

Management measurements

Norway

Landing obligations are not a subject in Norwegian fisheries, since it is mandatory to land all caught fish. Delivery obligations have nevertheless been put on about half the cod trawlers in order to see to it that fish is landed where it was supposed to, in the cases where processing firms were granted cod trawler licenses but where ownership to trawlers have been dissolve during the years. No limits exists to how much a vessel can land on a daily basis.

- safety limits to how much cargo a vessel can hold, and

- also a general rule that “a vessel should not carry more than it can take care of in a reasonable manner”,

- but no limits exist as to what is the limit for daily catches in order to enable a best possible raw material quality.

Iceland

Landing obligation

- None, except in coastal fisheries the fish has to be landed before 16:00 and in harbours in the fishing zone

- Delivery obligations are not in place in Iceland and no processing requirements

Fishing days – regulations/number of days

- Coastal fisheries have limitation (4 days pr. week/4 months)

- Gear restriction in the hook system

Quantity

- In the coastal fisheries system

- Max 650 kg pr. day/14 hours pr day

- TAC for each area

Closures

- Marine Institute has licences to introduce closures fishing areas if for example share of small fish

is too high according to landing or historical landing data Discard ban

- There are measurement’s in place to avoid discard

- Limited withdraw on unwanted catch form TAC

- Up to 5% of fish that is damage can be landed as VS fish special weighted and not withdraw from TAC

Newfoundland

Landing obligation

- must land all catch unless a species exemption is received from DFO

Minimum processing requirement

- cannot process at sea

Fishing season

- determined annually; reportedly based on ease of access to the fishery and not linked to market conditions

Gear restriction

- in place (e.g. fixed versus mobile gear)