Difference between revisions of "CPA"

Jacandrade (talk | contribs) |

Jacandrade (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 805: | Line 805: | ||

| WEF | | WEF | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The structure of the second pillar, efficiency enhancers, is similarly shown in Tables 2. This is a much more complex pillar than the first one, with nine subsections and 88 indicators. While some of the subsections here refer to areas mostly within the reach of government, such as higher education and training, other subsections deal with areas over which the firm themselves have more control, such as the access to and utilisation of inputs. Table 2 shows higher education and training, goods market efficiency and labour market efficiency, specific inputs used in fisheries, fish processing and aquaculture, financial market development, technological readiness and market size. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The structure of pillar III – innovation and business sophistication – is far simpler than that of the other two pillars. Here there are only two subsections, business sophistication and R&D innovation. There are 16 indicators within the former subsection and 10 within the latter. Most of these indicators refers to areas over which the firms have good control, but some are also related to areas there the government is more involved. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |Level||Weight||Source | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="width: 70%;" | 3rd pillar: Innovation and sophistication | ||

| + | |style="width: 15%;" |20% | ||

| + | |style="width: 15%;" | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |.A. Business sophistication||50%|| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.01 Local supplier quantity||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.02 Local supplier quality||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.03 State of cluster development||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.04 Nature of competitive advantage||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.05 Value chain breadth||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.06 Control of international distribution||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.07 Production process sophistication||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.08 Extent of marketing||3%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.09 Official marketing support - marketing||3%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.10 Marketing operations - wild fisheries||11%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.11 Marketing operations - aquaculture products||11%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.12 Competition among major suppliers - fisheries||11%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.13 Cooperation in the value chain - fisheries||11%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.14 Cooperation in the value chain - fish processing||11%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.15 Competition among major suppliers - fish processing||11%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....1.16 Cooperation along the value chain - aquaculture||11%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |.B. R&D Innovation||50%|| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.01 Capacity for innovation||8%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.02 Quality of scientific research institutions||8%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.03 Company spending on R&D||5%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.04 University-industry collaboration in R&D||8%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.05 Availability of scientists and engineers||8%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.06 PCT patent applications||5%||WEF | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.07 R&D Fishing technology fisheries||15%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.08 R&D Processing technology fisheries||15%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.09 R&D Processing technology fish processing||15%||Survey | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |....2.10 R&D - aquaculture equipment||15%||Survey | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

== Models == | == Models == | ||

Revision as of 23:43, 5 February 2018

Contents

Competitive Position Analyser

Introduction

The Competitive Position Analyser tool is the computerised version of the FACI survey and it is the implementation of the models described in this page. The concept of competitiveness can be traced back to early writing on economics in the 17th and 18th centuries, but has become ever more urgent in the last decades with rapid improvements in transport and communication and a higher level of globalisation. Although competitiveness may be measured by single indicators, such as productivity of labour, a deeper understanding of the competitive standing of firms and countries can be gained by employing multi-dimensional measurements.

The choice of methods depends on a variety of factors, including the perceived need for complexity, data availability and how the results are to be used. The Fisheries and Aquaculture Competitiveness Index (FACI) developed in this deliverable is modelled on the Fisheries Competitive Index (FCI) developed by the Directorate of Fresh Fish Prices in Iceland and the Norwegian College of Fishery Science at the University of Tromsø in 2004-2005. The FACI though expands on the FCI in two directions. First, by developing a national-level FACI that also includes aquaculture. Second, by designing a firm-level FACI that is intended to capture the views of operators of individual firms and is therefore less complex. The national-level FACI consists of 144 items, whereof 44 are taken from the WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 19 are based on data obtained from national, public sources and 81 are based on answers from a survey conducted among specialists in each country. . Whereas the information taken from the GCI analyses the overall competitiveness of the nation, the other sources will throw light on the competitiveness of the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. The firm-level FACI is based on a survey which in the case of firms engaged in the harvesting, processing or marketing of wild capture fish consists of 40 questions, and in the case of aquaculture firms consists of 45 questions.

The FACI was employed to analyse the competitiveness of three fisheries firms in Norway, one in Iceland and one in Newfoundland, and assess the competitive standing of Spain, Iceland, Norway and Vietnam. Newfoundland was also included in the national study, but the comparison is incomplete due to some gaps in the information collected. The firms in Newfoundland and Iceland were found to have a competitive edge over their Norwegian competitors, mostly due to their ability to fend of new entrants, flexible value-chains and high level of R&D development and innovation. At the national level, Iceland, Norway and Spain all ranked close .

Methods

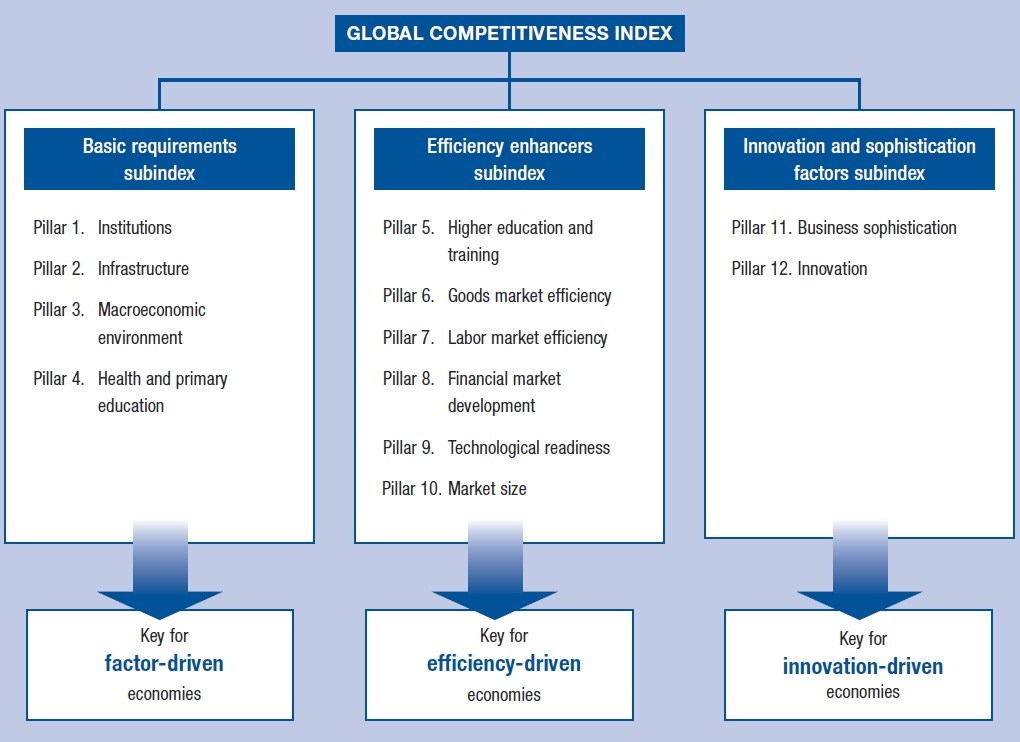

Currently, the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) is probably the most comprehensive index of its kind. The index defines competitiveness as the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. The most recent analysis covers 138 countries, with a combined output representing 98% of the world GDP. The index, which is compiled annually by the World Economic Forum, combines 114 indicators that capture concepts that matter for productivity and long-term prosperity. As shown in the figure below, these indicators are grouped into 12 pillars: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication, and innovation. These pillars are in turn organised into three sub-indexes: basic requirements, efficiency enhancers, and innovation and sophistication factors. The three sub-indexes are given different weights in the calculation of the overall Index, depending on each economy’s stage of development, as proxied by its GDP per capita and the share of exports represented by raw materials.

Fisheries and Aquaculture Competitiveness Index (FACI)

As outlined above, competitiveness can be measured in a number of ways, using both simple and more complex analytical tools. The choice of methods depends on a variety of factors, including the perceived need for complexity, data availability and how the results are to be used.

he FACI must be flexible enough to meet the needs of the two different end-users; industry and policymakers. With this in mind it was decided to develop two different kinds of competitiveness indexes; a firm-level FACI and a national-level FACI. The firm-level FACI is only intended to capture the views of operators of individual firms and therefore less complex. It is based on a survey which in the case of firms engaged in the harvesting, processing or marketing of wild capture fish consists of 40 questions, and in the case of aquaculture firms consists of 45 questions. The firms are able to access the firm-level FACI, complete the survey and then compare their answers to those provided by other operators. The degree of comparison will, of course, depend on the number of firms using the PrimeDSS, but provided the number of users is large enough, it would be possible to undertake comparison between firms in the same sectors both in the same country as well as between countries, as well as between different sectors. By thus benchmarking themselves against others, firms could gain a better understanding of their competitive standing.

The national-level FACI is modelled on the Fisheries Competitive Index (FCI) developed by the Directorate of Fresh Fish Prices in Iceland and the Norwegian College of Fishery Science at the University of Tromsø in 2004-2005 (Verðlagsstofa skiptaverðs, 2005). The FCI consists of 139 questions and observations which are split between six sub-indexes that make it possible to calculate scores both for the FCI as a whole as well as for individual sub-indexes. This further expands the use of the FCI. The index was applied to the Icelandic and Norwegian fish industries. The national-level FACI consists of 144 items, whereof 44 are taken from the WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 19 are based on data obtained from national, public sources and 81 are based on answers from a survey conducted among specialists in each country. Whereas the information taken from the GCI analyses the overall competitiveness of the nation, the other sources will throw light on the competitiveness of the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. The national-level FACI will therefore yield a comprehensive measure of competitiveness which takes both into account general conditions in the country as well as those that deal specifically with the sectors of interest.

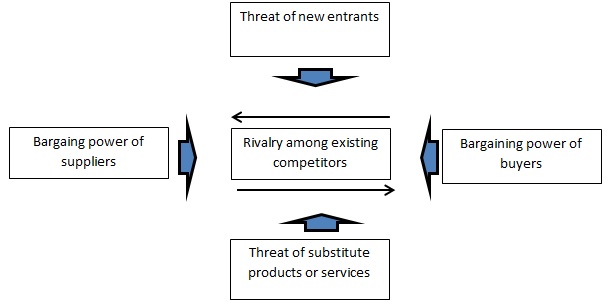

According to Porter (1998, 2008), the nature of competition is embodied in five competitive forces; (1) the threat of new entrants, (2) the threat of substitute products or services, (3) the bargaining power of suppliers, (4) the bargaining power of buyers, and (5) the rivalry among the existing competitors. As shown in the figure below, these forces do interact with each other. Their strength may also vary but together they determine long-term industry profitability.

The threat of entry puts a cap on the profit potential of an industry. When the threat is high, incumbents must keep prices low or increase production capacity to deter new competitors. Within each industry there are usually some entry barriers that deter new firms from entering the market, and give the incumbents some advantages. These may include economies of scale, network effects, customer switching costs, capital requirements, unequal access to distribution channels, restrictive government policy, expected retaliation of incumbents, and some other advantages not related to size, such as favourable geographic locations, and established brand identities.

The power of suppliers varies between industries, but in general a supplier is more powerful if is more concentrated than the industry it sells to, the supplier group does not depend heavily on the industry it is selling to, the firms face switching costs for changing suppliers and the products offered by suppliers are somewhat differentiated.

Buyers can capture more value by forcing down prices, demanding better quality or improved service, and play industry partners against each other. Analogous to suppliers, buyers have more leverage if they are few and large, the industry’s products are similar so that there are ample substitution possibilities, and there are low switching costs.

A high threat of substitutes will reduce profitability by placing a ceiling on prices. A firm can, however, distance itself from others through product performance, marking or other means. High rivalry among existing competitors will reduce the profitability of the firms in an industry. The rivalry can take many forms, including price discounting, new product innovations, advertising campaigns and service and quality improvements. Rivalry will be especially high in cases where there are many competitors and no clear industry leader, industry growth is slow and exit barriers are high. Although some market/firm/industry characteristics may be regarded as only belonging to one specific force category, other characteristics could plausible be classified in two or more different ways. Thus, the value of an output brand could impact on the bargaining power of buyers, threats of substitutes and rivalry among existing competitors. The firm-level FACI builds heavily on the theories of Porter (1998), taking into considerations all five aspects of competition outlined above. As stated earlier, this index is mostly intended for operators of fisheries and aquaculture firms who wish to analyse the competitive standing of their firm. The index consists of 40 questions – 45 in the case of aquaculture – that together yield a solid measure of competitiveness. This deliverable yields the results of a survey that was put to firm operators, but once the PrimeDSS becomes operational it will be possible to access a computerised version of the firm-level FACI, complete the survey online and then obtain a measure of the competitiveness of the firm, both by analysing the data and comparing the competitive standing of the firm to that of other firms. Each questions uses a seven-level Likert scale. Nine of the survey questions refer to the category threat of new entrants. They are as follows

- Institutional barriers (f. ex. licenses, quotas, regulations, location restrictions, water treatment)

- Investment barriers in capital (vessels, equipment, buildings)

- Other form of barriers (marketing, R&D, knowledge)

- Economies-of-scale in production

- Utilisation of economies-of-scale

- Geographical location

- Level of uncertainty in business environment

- Local availability of highly skilled labour

- Availability of qualified experts

The first three items all refer to concrete barrier to entry, such as licenses, quotas, investment, and R&D. The next two refer to the existence and utilisation of economies-of-scale, but companies that produce at a large scale enjoy a cost advantages that new entrants may have difficulties in matching. Geographical location refers to the fact that some firms are well located in terms of cost and ability to meet customer demand. An uncertain business environment may make entry less attractive, and the availability of skilled employees will certainly impact on the threat of entry. The bargaining power of suppliers is analysed on the basis of the following eight questions for fisheries firms (10 for aquaculture firms):

- Bargaining power of suppliers

- Competition among the major suppliers (fisheries)

- Current quality of raw material (fisheries)

- Ability of prices for raw material to reflect changes in (fisheries)

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Ability of prices for seed to reflect changes in (aquaculture)

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Ability of prices for feed to reflect changes in (aquaculture)

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Comparative access to raw material (fisheries)

- Comparative access to seed (aquaculture)

- Comparative access to feed (aquaculture)

- Access to supplier networks

The term “raw material” refers to landings of catch sourced by processors. Catches are by far the most important input for firms engaged in processing and marketing of wild capture fish, while for aquaculture firms the most important inputs are seed and feed. The interest here is in how well prices for these inputs reflect changes in quantity, quality and timing. The term “comparative access” refers to how firms regards their access to inputs (raw material, feed, seed) compared to their competitors. The bargaining power of suppliers is also assessed using a direct question on that issue. The bargaining power of buyers is analysed in terms of eight characteristics:

- Customers´ sensitivity to changes in product price

- Value of brand

- Loyal buyers

- Bargaining power of buyers

- Ability of output prices to reflect changes in

- Quantity

- Quality

- Timing

- Diversification of marketing options

Good brand value and loyal buyers will combine to make customers rather insensitive to changes in product prices. The survey also has questions on how firms view the price sensitivity of product prices, i.e. whether the firms regard their product price inelastic or elastic, as well as whether the bargaining power of buyers is weak or strong. Diversification of marketing options refers to whether the firm depends on a single buyer for its product or many buyers. The bargaining power of buyers may also be affected by how well output prices reflect changes in quantity, quality and timing of sale

The bargaining power of buyers is very closely linked to the threat of substitute products or services. Some of the items listed under the bargaining power of buyers, such as customers’ sensitivity to price changes, brand value and consumer loyalty, could just as easily have been listed under substitutes. Here, only two items are classified in this category, namely:

- Production to a niche market

- Availability of substitutes

Customers in niche markets are often willing to pay a premium price for a product that well satisfies their needs. These markets are often characterised by a strong brand and consumer loyalty. The two survey questions here refer to whether the firm is producing to a niche market, and whether substitutes to the product are available in the market. Most of the survey questions in the firm-level FACI are here grouped under the heading “rivalry among existing competitors”. However, many of these items could equally well have been categorised differently. These questions are on the following topics:

- R&D collaboration with technology firms

- Importance of R&D for operation and possibility to increase value added

- Importance of innovation for competitive advantage

- Ability of firm’s part of the value chain to respond to changes in market conditions

- Ability of the whole value chain to respond to changes in market conditions

- Importance of third-party audited labels

- Strength of competitive strategy

- Market share of firm

- Level of cost leadership

- Sophistication of production technology compared to best practice

- Quality of sites for production facilities

- Flexibility to adapt to unpredictable events

- Ability of risk management and insurance to protect against unpredictable negative shocks

- Comparative seed costs (aquaculture)

- Comparative feed costs (aquaculture)

- Comparative production losses due to diseases or other causes (aquaculture)

The first three questions refer to R&D and innovation activities within the firm, to which degree they are done in close collaboration with high-tech firms, and how important they are for increased value added and competitive advantage. Flexibility of the value chain – both as regards the firm itself and the whole value chain – is also important for firms facing competition. Third-party labelling has become very important in the food industry, not least for fisheries and aquaculture. Labelling may open access to markets and also indicate sustainable and environmental friendly production. The market share of firms is important, as is the level of cost leadership. Firms are also asked to indicate how sophisticated their production facilities are compared to their competitors, and assess the quality of the sites used for their production facilities. Two questions refer to the ability of the firms to adjust to unpredictable events, and three questions focus on the costs of feed and seed relative to the firm’s competitors, and comparative production losses due to fish diseases and other causes.

The firm-level FAC yields both an overall score as well as a score for each of the five competitive forces where the former is calculated as the simple average of the other five scores.

National-level FACI

The national-level FACI is a comprehensive measure that includes both factors influencing each country’s overall competitiveness as well as factors that specifically relate to the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. Most of the indicators related to overall competitiveness are taken from the Global Competitiveness Index, published by the World Economic Forum (2016), but information on the other, more specific indicators was obtained through surveys and from public data collection agencies.

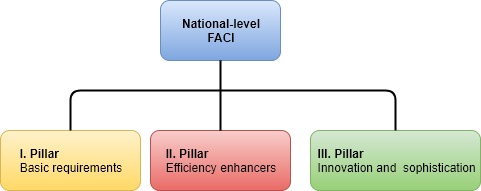

The national-level FACI consists of three pillars; (I) basic requirements, (II) efficiency enhancers, and (III) innovation and sophistication. In contrast to the firm-level FACI, the national-level FACI yields a weighted overall score for each country, as well as a weighted score for each pillar and the sub-indexes contain therein. Basic requirements weigh 30% of the total score, efficiency enhancers 50% and innovation and sophistication 20%.

The first pillar – basic requirements – comprises elements that are essential if firms are to thrive in a competitive, international world. As noted by Acemoglu and Robinson (2012), economic prosperity depends above all on the inclusiveness of economic and political institutions, where inclusiveness is defined as the situation where a large number of people have a say in political decision-making. By contrast, extractive institutions allow a certain elite to rule over and exploit others, thus preventing firms from enjoying competition on a level playing field. As shown in Table 1, there are two subsections within the first pillar, institutions and infrastructure. Institutions are then further subdivided into public institutions and management of fisheries and aquaculture. Public institutions are then finally divided into property rights and public sector performance. There is just one indicator for property rights, namely property rights, but within public sector performance there are three indicators. Well defined and secure property rights are essential for any market-based activity, as are well functioning courts and legal system that make it easy for firms to challenge government actions and/or regulations. Transparent government policy making is also important. The burden of government regulation must however not become too great. For firms operating within the fisheries and aquaculture sectors, it is also important how well these activities are managed by policy makers.

Table 1 Structure of the first pillar, Basic requirements.

| Level | Weight | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1st pillar: Basic requirements | 30% | |

| : A. Institutions | 75% | |

| :: I. Public institutions | 33% | |

| ::: 1. Property rights | 50% | |

| :::: 1.01 Property rights | 100% | WEF |

| ::: 2. Public sector performance | 50% | |

| :::: 2.01 Burden of government regulation | 33% | WEF |

| :::: 2.02 Efficiency of legal framework in challenging regulations | 33% | WEF |

| :::: 2.03 Transparency of government policy making | 33% | WEF |

| :: II. Fisheries management | 33% | |

| ::: 3. Stability | 33% | |

| :::: 3.01 Transparency of fisheries management | 33% | Survey |

| :::: 3.02 Objectives of fisheries management | 33% | Survey |

| :::: 3.03 Stability of the allocation of fishing rights | 33% | Survey |

| ::: 4. Research and advice | 33% | |

| :::: 4.01 Actual vs recommended fishing mortality | 20% | Data |

| :::: 4.02 Extent of information gathering by marine research | 20% | Survey |

| :::: 4.03 Information gathering by marine research | 20% | Survey |

| :::: 4.04 Accuracy of forecasts of marine research | 20% | Survey |

| :::: 4.05 Impact of marine research on investments and operation | 20% | Survey |

| ::: 5. Monitoring and inspection | 33% | |

| :::: 5.01 Efficiency of the management system | 50% | Survey |

| :::: 5.02 Illegal/excess catches | 50% | Survey |

| :: III. Aquaculture management | 33% | |

| ::: 6. Stability | 50% | |

| :::: 6.01 Transparency of aquaculture management | 25% | Survey |

| :::: 6.02 Objectives of aquaculture management | 25% | Survey |

| :::: 6.03 Stability of the allocation of the aquaculture licenses | 25% | Survey |

| :::: 6.04 Efficiency of management - aquaculture | 25% | Survey |

| ::: 7. Research and advice | 50% | |

| :::: 7.01 Extent of information gathering by research for aquaculture | 100% | Survey |

| : B. Infrastructure | 25% | |

| :: I. Transport infrastructure | 100% | |

| :::: 8.01 Quality of overall infrastructure | 20% | WEF |

| :::: 8.02 Communication network needs | 20% | Survey |

| :::: 8.03 Communication network restrictions | 20% | Survey |

| :::: 8.04 Cost of domestic transportation | 20% | Survey |

| :::: 8.05 Cost of cross-border transportation | 20% | Survey |

Table 1 also shows the weighing structure of the FACI. As noted above, the first pillar, Basic requirements, carries a weight of 30%, with institutions thereof weighing 75% and infrastructure weighing 25%. Within institutions, public institutions weigh 33%, fisheries management 33% and aquaculture management 33%. Within public institutions, property rights weigh and public sector performance each weigh 50%. Finally, each of the three indicators of public sector performance weighs 33%. The weight of each section and indicators is shown in the second-last column of Table 1, while the sources are shown in the last column of the table. WEF refers to the 2016-2017 Global Competitiveness Index carried out by the World Economic Forum, data refers to data collected from official sources, and survey refers to the survey carried out among experts in each country.

Table 2 Structure of the second pillar, Efficiency enhancers. Subsections A-C.

| Level | Weight | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd pillar: Efficiency enhancers | 50% | |

| _A. Higher education and training | 5 | |

| __I. Quality of education | 25% | |

| ____1.01 Quality of the education system | 33% | WEF |

| ____1.02 Quality of math and science education | 33% | WEF |

| ____1.03 Quality of management schools | 33% | WEF |

| __II. On-the-job training | 75 | |

| ____2.01 Local availability of specialized training services | 10% | WEF |

| ____2.02 Extent of staff training | 10% | WEF |

| ____2.03 Training and education fisheries | 30% | Survey |

| ____2.04 Training and education fish processing | 30% | Survey |

| ____2.05 Training and education aquaculture | 30% | Survey |

| _B. Goods market efficiency | 10% | |

| __I. Competition | 67% | |

| ___3. Domestic competition | 50% | |

| ____3.01 Intensity of local competition | 5% | WEF |

| ____3.02 Extent of market dominance | 5% | WEF |

| ____3.03 Effect of taxation on incentives to invest | 8% | WEF |

| ____3.04 Total tax rate | 8% | WEF |

| ____3.05 Competition for fishing rights (quota) | 15% | Survey |

| ____3.06 Market for fresh fish - fisheries | 15% | Survey |

| ____3.07 Market for fresh fish - fish processing | 15% | Survey |

| ____3.08 Competition between marketing/distributors - marketing | 15% | Survey |

| ____3.09 Competition between companies that market and distribute seafood products | 15% | Survey |

| ___4. Foreign competition | 50% | |

| ____4.01 Prevalence of non-tariff barriers | 15% | WEF |

| ____4.02 Trade-weighted average tariff rate | 15% | WEF |

| ____4.03 Current markets - free trade agreements | 45% | Survey |

| ____4.04 Potential markets - free trade agreements | 25% | Survey |

| __II. Quality of demand conditions | 33% | |

| ____5.01 Degree of customer orientation | 10% | WEF |

| ____5.02 Buyer sophistication | 10% | WEF |

| ____5.03 Product development - fish processing | 40% | Survey |

| ____5.04 Product development - aquaculture processing | 40% | Survey |

| _C. Labour market efficiency | 10% | |

| __I. Flexibillity | 25% | |

| ____6.01 Flexibility of wage determination | 33% | WEF |

| ____6.02 Hiring and firing practices | 33% | WEF |

| ____6.03 Effect of taxation on incentives to work | 33% | WEF |

| __II. Efficient use of talent | 25% | |

| ____7.01 Pay and productivity | 10% | WEF |

| ____7.02 Reliance on professional management | 10% | WEF |

| ____7.03 Productivity of fishermen | 30% | Data |

| ____7.04 Wage system fisheries | 30% | Survey |

| ____7.05 Productivity of employees fish processing | 30% | Data |

| ____7.06 Wage system fish processing | 30% | Survey |

| ____7.07 Productivity of labor aquaculture | 30% | Data |

| ____7.08 Labour skills and productivity - aquaculture | 30% | Survey |

| __III. Supply of labour | 25% | |

| ____8.01 Supply of qualified officers | 20% | Survey |

| ____8.02 Supply of skilled fishermen | 20% | Survey |

| ____8.03 Supply middle management fish processing | 20% | Survey |

| ____8.04 Supply of skilled labour fish processing | 20% | Survey |

| ____8.05 Supply middle management aquaculture | 20% | Survey |

| ____8.06 Supply of skilled labour aquaculture | 20% | Survey |

| __IV. Cost of labour | 25% | |

| ____9.01 Labour cost fisheries | 50% | Data |

| ____9.02 Labour cost fish processing | 50% | Data |

| _D. Fisheries specific inputs | 15% | |

| __I. Property rights | 20% | |

| ____10.01 Permanency of fisheries rights. | 50% | Survey |

| ____10.02 Transfers of fishing rights between firms | 50% | Survey |

| __II. Capacity utilization | 20% | |

| ____11.01 Transfers of fishing rights between vessels | 25% | Survey |

| ____11.02 Impact of quota system on capacity utilisation | 25% | Survey |

| ____11.03 Stability of catch for the 5 most important species. | 25% | Data |

| ____11.04 Impact of authorities on investment decisions | 25% | Survey |

| __III. Cost items | 30% | |

| ____12.01 Special taxation fishing | 50% | Data |

| ____12.02 Oil price | 50% | Data |

| __IV. Profitability | 30% | |

| ____13.01 Profit margin | 35% | Data |

| ____13.02 Capital turnover | 20% | Data |

| ____13.03 Financial strength | 15% | Data |

| ____13.04 Ability to use economies of scale | 20% | Survey |

| ____13.05 Ability to use economies of scope | 10% | Survey |

| _E. Fish processing specific inputs | 15% | |

| __I. Capacity utilization | 20% | |

| ____14.01 Distribution of the catch within the year | 50% | Data |

| ____14.02 Timing of wetfish availability | 50% | Survey |

| __II. Cost items | 30% | |

| ____15.01 Cost of electricity | 50% | Data |

| ____15.02 Supply and cost of fresh water - fish processing | 50% | Survey |

| __III. Profitability | 30% | |

| ____16.01 Profit margin | 35% | Data |

| ____16.02 Capital turnover | 20% | Data |

| ____16.03 Financial strength | 15% | Data |

| ____16.04 Ability to use economies of scale | 20% | Survey |

| ____16.05 Ability to use economies of scope | 10% | Survey |

| _F. Aquaculture specific inputs | 15% | |

| __I. Property rights | 20% | |

| ____17.01 Transfers of licenses between firms - aquaculture | 100% | Survey |

| __II. Capacity utilization | 20% | |

| ____18.01 Impact of regulations on capacity utilisation - aquaculture | 100% | Survey |

| __III. Cost items | 30% | |

| ____19.01 Cost of electricity - aquaculture | 15% | Data |

| ____19.02 Supply and cost of seedstocks | 30% | Survey |

| ____19.03 Supply and cost of feed | 55% | Survey |

| __IV. Profitability | 30% | |

| ____20.01 Profit margin | 35% | Data |

| ____20.02 Capital turnover | 20% | Data |

| ____20.03 Financial strength | 15% | Data |

| ____20.04 Ability to use economies of scale | 20% | Survey |

| ____20.05 Ability to use economies of scope | 10% | Survey |

| _G. Financial market development | 5% | |

| __I. Efficiency | 100% | |

| ____21.01 Financial services meeting business needs | 33% | WEF |

| ____21.02 Financing through local equity market | 33% | WEF |

| ____21.03 Ease of access to loans | 33% | WEF |

| _H. Technological readiness | 15% | |

| __I. Technological adoption | 10% | |

| ____22.01 Availability of latest technologies | 50% | WEF |

| ____22.02 Firm-level technology absorption | 50% | WEF |

| __II. Fisheries technology | 30% | |

| ____23.01 Technical level of vessels and mechnical equipment | 33% | Survey |

| ____23.02 Fishing technology | 33% | Survey |

| ____23.03 Processing technology on board | 33% | Survey |

| __III. Fish processing technology | 30% | |

| ____24.01 General technology - fish processing | 100% | Survey |

| __IV. Aquaculture technology | 30% | |

| ____25.01 General technology - aquaculture | 100% | Survey |

| _I. Market size | 10% | |

| __I. Domestic market size | 50% | |

| ____26.01 Domestic market size index | 100% | WEF |

| __II. Foreign market size | 50% | |

| ____27.01 Foreign market size index | 100% | WEF |

The structure of the second pillar, efficiency enhancers, is similarly shown in Tables 2. This is a much more complex pillar than the first one, with nine subsections and 88 indicators. While some of the subsections here refer to areas mostly within the reach of government, such as higher education and training, other subsections deal with areas over which the firm themselves have more control, such as the access to and utilisation of inputs. Table 2 shows higher education and training, goods market efficiency and labour market efficiency, specific inputs used in fisheries, fish processing and aquaculture, financial market development, technological readiness and market size.

The structure of pillar III – innovation and business sophistication – is far simpler than that of the other two pillars. Here there are only two subsections, business sophistication and R&D innovation. There are 16 indicators within the former subsection and 10 within the latter. Most of these indicators refers to areas over which the firms have good control, but some are also related to areas there the government is more involved.

| Level | Weight | Source |

| 3rd pillar: Innovation and sophistication | 20% | |

| .A. Business sophistication | 50% | |

| ....1.01 Local supplier quantity | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.02 Local supplier quality | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.03 State of cluster development | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.04 Nature of competitive advantage | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.05 Value chain breadth | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.06 Control of international distribution | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.07 Production process sophistication | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.08 Extent of marketing | 3% | WEF |

| ....1.09 Official marketing support - marketing | 3% | Survey |

| ....1.10 Marketing operations - wild fisheries | 11% | Survey |

| ....1.11 Marketing operations - aquaculture products | 11% | Survey |

| ....1.12 Competition among major suppliers - fisheries | 11% | Survey |

| ....1.13 Cooperation in the value chain - fisheries | 11% | Survey |

| ....1.14 Cooperation in the value chain - fish processing | 11% | Survey |

| ....1.15 Competition among major suppliers - fish processing | 11% | Survey |

| ....1.16 Cooperation along the value chain - aquaculture | 11% | Survey |

| .B. R&D Innovation | 50% | |

| ....2.01 Capacity for innovation | 8% | WEF |

| ....2.02 Quality of scientific research institutions | 8% | WEF |

| ....2.03 Company spending on R&D | 5% | WEF |

| ....2.04 University-industry collaboration in R&D | 8% | WEF |

| ....2.05 Availability of scientists and engineers | 8% | WEF |

| ....2.06 PCT patent applications | 5% | WEF |

| ....2.07 R&D Fishing technology fisheries | 15% | Survey |

| ....2.08 R&D Processing technology fisheries | 15% | Survey |

| ....2.09 R&D Processing technology fish processing | 15% | Survey |

| ....2.10 R&D - aquaculture equipment | 15% | Survey |

Models